Consider Bell from Camal Pirbhai and Camille Turner’s Wanted series—an immense conceptual photograph that has everything and nothing to do with Canada at the same time. Wanted takes newspaper ads placed by Canadian slave owners claiming their runaway slaves and recreates them as beguiling, defiant photographs. These images run against Canada’s self-serving narrative as deeply uncool, endlessly apologetic and cripplingly passive-aggressive.

Bell is none of those things, drawing on Toronto’s long history of posing as New York in its after-five campiness; at the same time, it bears an indexical relation to missing and murdered Indigenous women who, like those fugitive slaves, simply disappeared.

“Every. Now. Then: Reframing Nationhood”—in which Bell appears—is on now at the Art Gallery of Ontario. And the show is, thankfully, uninterested in being a Colonialism 101 for old arts patrons. Instead, it concerns itself with more than justifying the humanity of Black and Indigenous people.

Curated by Andrew Hunter, Anique Jordan and Quill Christie-Peters, the exhibition is an impressive survey of works that are diverse, challenging and genuinely surprising. After a summer of ambivalence and resistance regarding the sesquicentennial, the experience of seeing familiar artists and activists from Toronto’s social justice community and Canada’s contemporary art scene feels urgent and relevant.

Detail of Ruth Cuthand’s Don’t Breathe, Don’t Drink. Photo: via DC3 Art Projects.

Detail of Ruth Cuthand’s Don’t Breathe, Don’t Drink. Photo: via DC3 Art Projects.

Some highlights:

A cast of a fossilized form of a giant sea scorpion is placed adjacent to Ruth Cuthand’s Don’t Breathe, Don’t Drink; Cuthand’s piece consists of 94 vessels with beaded resin sculptures on a beaded blue tarp, representing 94 First Nations under boil-water advisories. Together, the ancient artifact and the contemporary artwork elicit a sense of despair. It reminds us that colonialism is as infectious as it is insidious, lingering in even the water. Cuthand’s piece, created in 2016, is all the more devastating in the wake of Canada 150—now, 153 boil water advisories, many of them in Ontario, continue to be in effect in First Nations communities.

Walking into The Possession Project, an “exhibition within an exhibition” by emerging GTA-based artists, I was devastated by Fluke, an installation and poetry reading by Britta B. “You are not a fluke!” it proclaims, an unexpected message that I didn’t know I needed. Guests are encouraged to draw a hand-written affirmation from a jar—mine read, “A smile on your face makes others happy”—and as platitudinal as it was, the stubborn, childlike sincerity of the message rang loud and true. The indiscriminate care this piece extends is real and genuine.

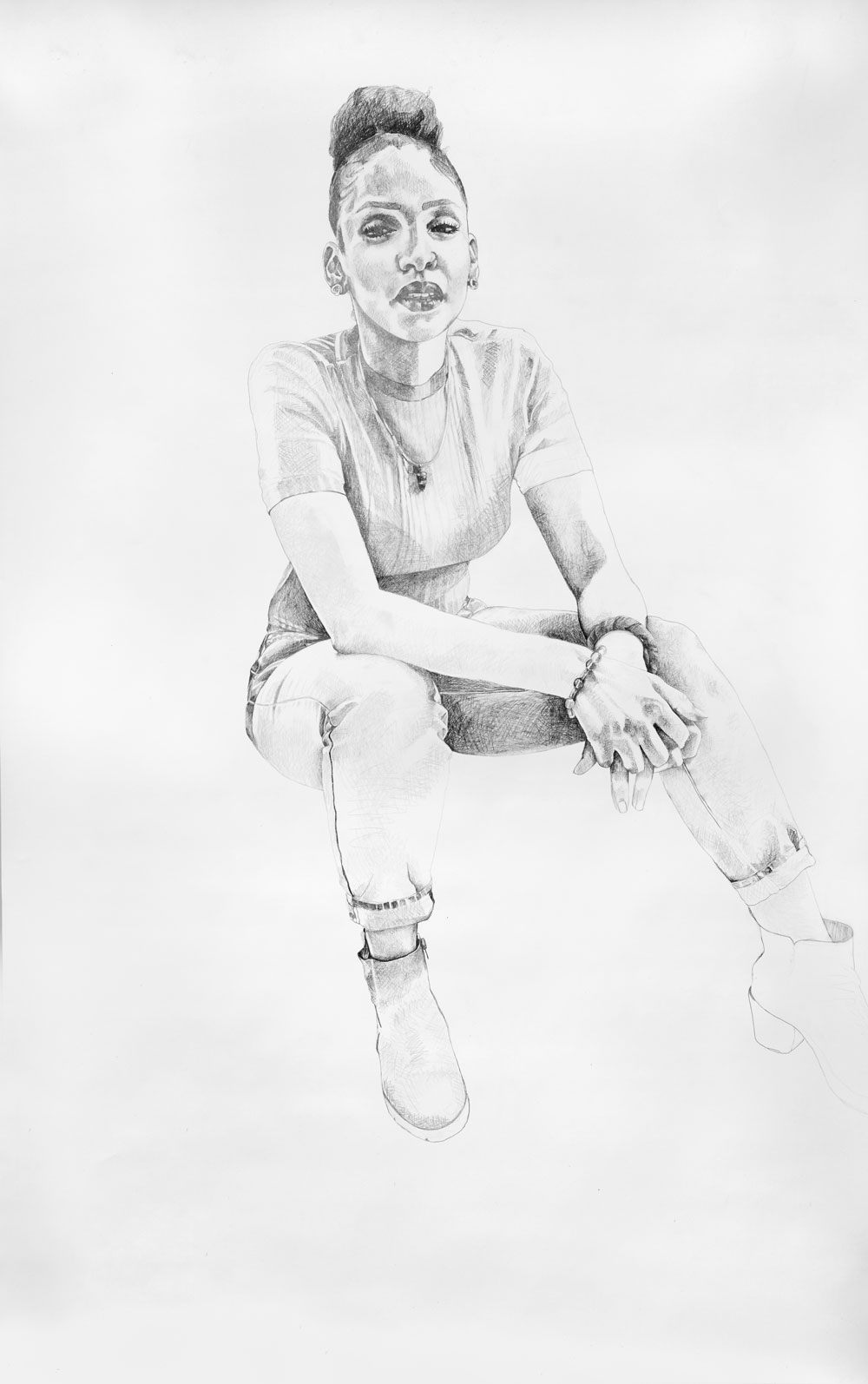

Radical notions of care are put forward in Syrus Marcus Ware’s Baby, Don’t Worry, You Know That We Got You, four enormous pencil drawings of members of Toronto’s social justice community—some of which I had encountered at the Gladstone Hotel’s Art Hut during “Black Art City,” an exhibition loosely based around Black Lives Matter’s Tent City outside of Toronto Police Headquarters last year. Reinforcing BLM’s radical notions of indiscriminate care by immortalizing some of its greatest proponents, among them BLMTO co-founder Yusra Khogali, Baby, Don’t Worry provides, in part, a response to the blatantly false and racist characterization of BLM as “violent” by liberal and conservative commentators alike.

Syrus Marcus Ware, Baby, Don’t Worry, You Know That We Got You, 2017. Graphite on paper, 365.9 × 609.8 cm. Courtesy of the artist. © Syrus Marcus Ware.

Syrus Marcus Ware, Baby, Don’t Worry, You Know That We Got You, 2017. Graphite on paper, 365.9 × 609.8 cm. Courtesy of the artist. © Syrus Marcus Ware.

Here, it occurs to me that Black art that isn’t immediately legible as Black is construed differently in the absence of racialized signifiers. Whether or not an artist chooses to foreground their identity is a meaningful choice: On the one hand, the tendency of racialized artists to move away from abstraction can be read as a result of the fact that white supremacy deliberately obscures or misrepresents the experiences of racialized people. On the other hand, Capital-B Black art in institutional spaces can often feel coerced into crystal-clear representation, being privileged primarily if it’s legible (to white audiences) or otherwise erudite in its representation of Black experience.

These thoughts on the representation of Black people informed my experience of Xiong Gu’s Illuminated Niagara Falls, a towering photographic documentation of migrant workers from Jamaica and Mexico in Southern Ontario. They also affected my reading of the early tintype photographs of Black Canadians in the “Free Black North” exhibition two floors below. Where these two projects lean on representation as proof of existence of marginalized people, and as a justification of their humanity, the wider scope of “Every. Now. Then” takes it a step further, directing, in a sophisticated manner, how that very presence is narrativized.

Indeed, the thematic density and clarity of “Every. Now. Then.” foregrounds bodies and identities in ways that preserve their autonomy—and more importantly, it doesn’t preserve them for the consumption of others, a common criticism of non-Indigenous curation of Indigenous art. In nearly every instance here, artist and subject coolly meets the gaze of curator and viewer.

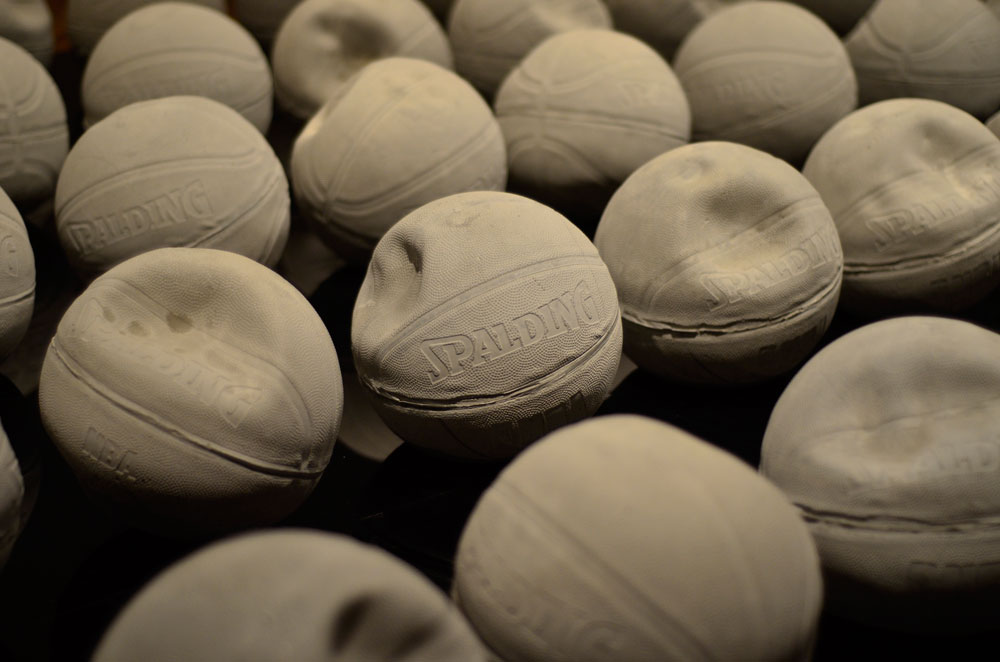

Esmaa Mohamoud, Heavy Heavy (Hoop Dreams), 2016. Cast concrete, 304.8 × 304.8 cm. Collection of the artist. © Esmaa Mohamoud.

Esmaa Mohamoud, Heavy Heavy (Hoop Dreams), 2016. Cast concrete, 304.8 × 304.8 cm. Collection of the artist. © Esmaa Mohamoud.

Esmaa Mohamoud’s One of the Boys and Heavy, Heavy (Hoop Dreams) contend with these gazes by inverting the mythologies erected around Black men. In the former, Raptors jerseys are reworked into grandiose ballgowns, pointing towards the rigidity of gender roles and, by extension, expectations placed on Black men. The literal and metaphorical weight of such expectations is reflected in the latter work: concrete casts of partially deflated basketballs, vulnerable in form but resolute in their materiality. “The concrete basketballs are physically heavy but also so fragile—the nature of concrete is to crack, so eventually these will break apart,” Mohamoud explains in the catalogue text.

One would be remiss not to acknowledge the work of the curators in using every available square inch of the AGO’s fourth floor to have institutional mainstays like Tim Pitsiulak and Robert Houle rub shoulders with contemporaries both emerging and unknown. Bearing witness to such intriguing mix of works in a condensed space felt akin to touring several galleries in a single visit, complicating and expanding an ongoing narrative that is far more complex than any imagined by a royal commission.

Presenting such a complex, sentient portrayal of Canadian identity, politics and culture is rife with risks and pitfalls, but Hunter, Jordan and Christie-Peters have navigated all of them deftly, incorporating diversity, social justice advocacy and community outreach in a riveting presentation that will be referenced and discussed for years to come.

Vidal Wu is the editorial resident at Canadian Art.

Camille Turner and Camal Pirbhai, Bell (Wanted Series), 2016. Digital photograph, dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artists. © Camille Turner and Camal Pirbhai. Photo: Christina Sideris.

Camille Turner and Camal Pirbhai, Bell (Wanted Series), 2016. Digital photograph, dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artists. © Camille Turner and Camal Pirbhai. Photo: Christina Sideris.