I will start small: with the spices in the kitchen cupboard when I was a child. The contained assortment of little bottles and mason jars with their handwritten labels that I would rearrange, and that I took such pleasure in ordering. A deep satisfaction when a number of elements fall into place. I feel this when the words in a sentence land just right in translation.

It began under the eaves of a 17th-century Hotel-Dieu, now a translation residency. It began with a rush of a crush between library stacks at the Bibliothèque nationale in Montreal. It began on the dance floor at a party on Montrose Avenue. And it began in the south of France, after midnight, with a banjo playing at an open window.

I have translated four novels in my career, and I can romanticize each of their beginnings. What came after was messy, arduous, dizzying, sometimes devastating, but not without tinges of that first romance. There’s such intimacy to translation. Such nearness in listening that closely to the words of someone else.

I have said, as have others, that no one will read your work like a translator. No reader, critic, journalist or jury will ever spend so much time poring over the phrases you’ve chosen to lay out in just this way. To inhabit, and then be inhabited by, the words.

This residing-in and being haunted by words happens when I’m writing, too. Waves of phrases that turn themselves over and over and shift in the liminal times. As a writer, I am always looking for ways to make language new; translating from another language enriches my thinking andstretches the edges of my English. My first book of poems, Everything, now, was sparked by my translation of a poetic novel—I used translated phrases as leaping-off points for my own pieces. I lived among the words of Turkana Boy for so long, and made them even further my own by absorbing them into poems, I had to remind myself at times that there was another, first author.

Like any freelancer, literary translators have the flexibility to work from a variety of places— including planes, trains, over the nursing baby’s shoulder, and, yes, the south of France. There is the obvious flip side to this freedom—we also never get to have a true vacation. We live without a safety net—no sick days, benefits or pension plan—but the luxury of keeping my own hours is one I would not give up.

The Canada Council sets the rate for literary translation at 18 cents per word of fiction (other, non-literary contracts tend to pay somewhere between 20 and 25 cents per word) and funds translations of books by Canadian authors into English, French or an Indigenous language. An average 200-to-250-page novel pays the translator about $9,000. Nearly every colleague I asked said they’d rather not break this down into an hourly wage because it would be too depressing. I’m reminded of a breadbaking venture with three friends when I was 23: every Tuesday, we woke up at 4 a.m. and rode our bikes to the city park where we lit the fires in the brick ovens, and then, 11 hours later, crammed the borrowed Fiat full of fresh loaves and drove across the city to the farmer’s market. It was intensely satisfying work. And when we counted the money at the end of the day, we realized we were working for $1.75 per hour.

The hourly rate for translation probably works out to something closer to $20 to $50, but can vary immensely from day to day, page to page, and text to text just like writing, which belongs to a different kind of time. Sometimes a passage can take hours to research and recreate in the language of arrival. Other times the flow feels sweet and easy, and whole pages pass in very little time.

Even though we do comparatively well in Canada, with the council’s standard rate allowing us to avoid the undercutting and outbidding that goes on in some other countries (Spain and France, for example), most literary translators I know have a second job which allows them to finance their “literary habit.” They are professors, commercial translators, editors, teachers. The ones who manage to support themselves translate at least five times as many books per year as I do, with much tighter deadlines. I myself have worked as a yoga teacher, a prep cook, a research assistant, and have taken on hundreds of shorter, non-literary contracts. I’ve been helped by grants and bursaries for writers and translators, and have also chosen to live inexpensively (when I translated my first book, I paid $380 per month in rent and didn’t own anything more costly than a nice bicycle). I’ve been able to luxuriate in translation the way I have, stretching it out in a way similar to writing, because I am not relying on literary translation to support myself.

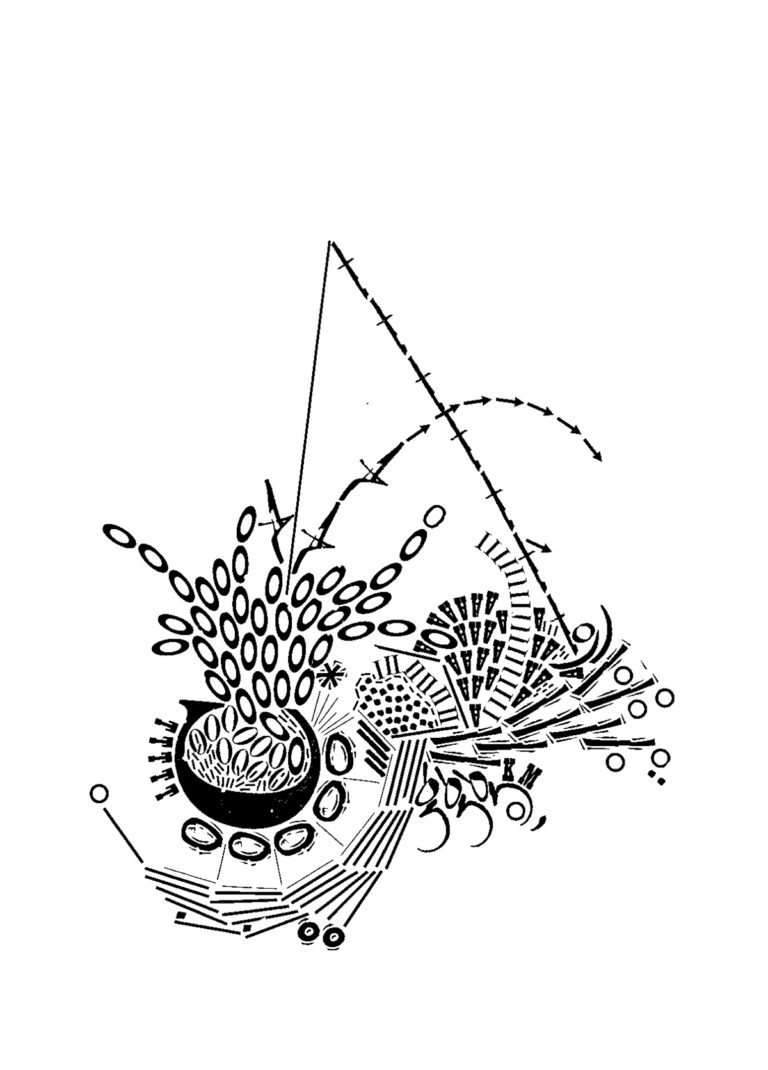

Kelly Mark, Boiling C, 2001. Letraset on archival matte board, 35.5 x 27.9 cm. Private collection. Courtesy Olga Korper Gallery.

Kelly Mark, Boiling C, 2001. Letraset on archival matte board, 35.5 x 27.9 cm. Private collection. Courtesy Olga Korper Gallery.