Henry Speck, born in 1908 in Turnour Island, BC, was a prolific First Nations artist of the mid-20th century. Self-taught in watercolour and woodcarving, and located for most of his life in the traditional Kwakwaka’wakw territory of Alert Bay, he created more than 600 paintings, among other works, before dying in 1971.

Until recently, however, the majority of Speck’s paintings were contained in three private west-coast collections, and were rarely seen in public.

This week, Vancouver collector and dealer Sarah Macaulay hopes to open up awareness for Speck’s unique legacy when she features his paintings at the Outsider Art Fair in New York.

“I felt like because Henry Speck was alien to the prevailing, dominant culture, and unconnected to a kind of conventional art world not really by choice but by circumstance, that it would be interesting to take his work and put it in that context and see how it reads,” Macaulay says.

Macaulay first became aware of Speck’s art when some of his paintings were highlighted in a solo show at Vancouver’s Satellite Gallery in 2012. What followed, she says, was “a wild goose chase” to track down some of his paintings for her own collection. And now, she is bringing them to others.

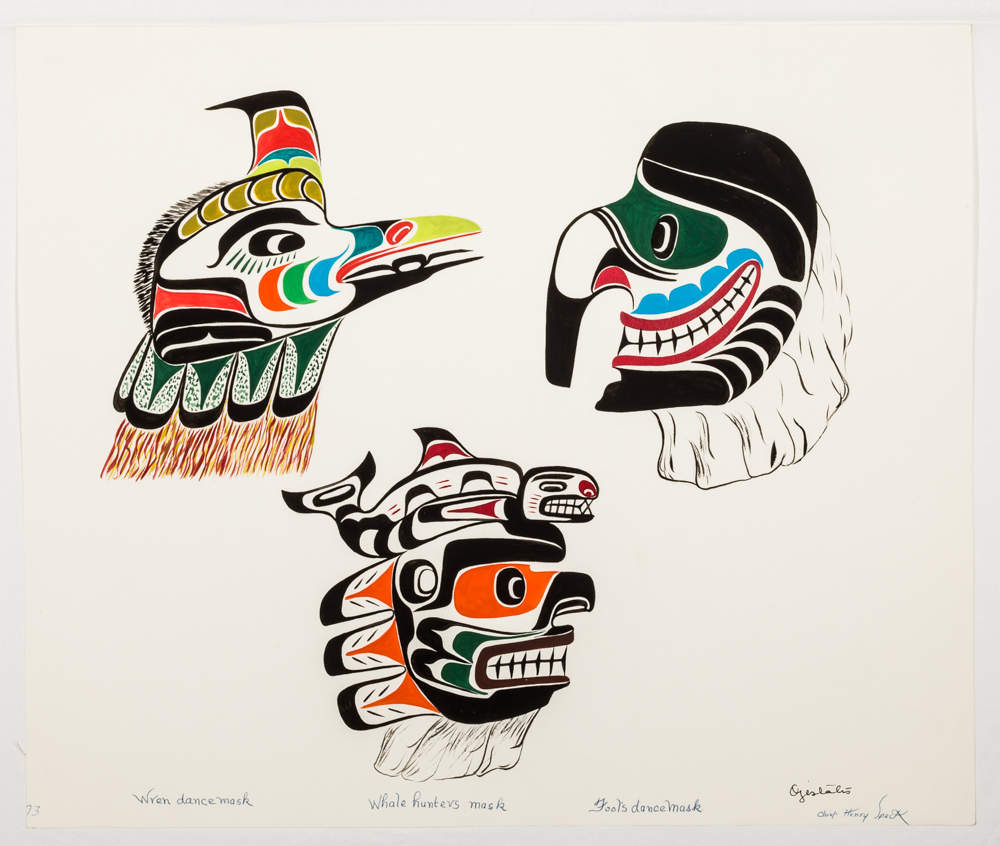

“Working in this medium, painting on paper, seemed to give [Speck] a lot of freedom and he used this freedom to create highly original ways of representing Kwakwaka’wakw cultural practice,” says Karen Duffek, who co-curated that 2012 Satellite Gallery exhibition with Marcia Crosby.

Also a curator at the UBC Museum of Anthropology, Duffek notes that Speck’s paintings of Kwakwaka’wakw dancers, masks and legends offers a chance to consider the dramatic complexities in his life.

“He is creating these images in his own very unique idiosyncratic new way, but they are all about reaffirming his ancestral origins, his culture,” Duffek says. “So there is that contradiction there which parallels the experience in his life of trying to deal with the rupture between his culture and the impact of colonization.”

Not just complex, but problematic, says OCADU Indigenous Visual Culture professor Ryan Rice, is the contemporary attempt to label Speck as an outsider artist.

“It is problematic in general,” says Rice, who is also co-founder and former director of the Aboriginal Curatorial Collective. He says the outsider art label “is created because it carries commodification, it carries a value. I don’t think people necessarily name themselves as outsider artists. Other people put that label on them and then it enters that realm. I don’t know any artists who would consider themselves outsider artists within Indigenous history and I don’t think anyone writing Canadian art history or Indigenous art history is placing that label on native artists; not that I’ve ever come across.”

Rice’s observations around the increasing value of the “outsider art” label are supported by the fact a number of art-world heavy hitters are visiting the Outsider Art Fair this year to discuss this matter. A panel called “The Shifting Center” gathers superstar curator Massimiliano Gioni—who famously included so-called outsider art in the 2013 Venice Biennale exhibition—as well as Jens Hoffmann and Frieze co-editor Dan Fox to address how large art institutions collect and exhibit outsider art, and whether outsider art has begun to be taken in by the mainstream.

Rice also says more specifically that he doesn’t see Speck as an outsider artist.

“I couldn’t consider him an outsider artist; I wouldn’t consider Daphne Odjig an outsider artist; I don’t see Bill Reid as an outsider artist,” Rice elaborates. “I think it’s a term that comes with too much baggage and it doesn’t reflect on the time.”

In fact, during his lifetime Speck was (and he remains) well known in many Kwakwaka’wakw communities, not only for his artwork but also his status as a hereditary chief, a dancer, and a ceremonial songwriter. He was also known for his work as a “great modernizer,” says Duffek, as he was responsible for building a power plant and bringing electricity to his community, as well as other kinds of infrastructure.

Considering Henry Speck as an outsider artist may also conflict with the fact that he also did enjoy some commercial and institutional success during his lifetime, exhibiting at the New Design Gallery in Vancouver—one of the first contemporary art galleries there. Speck’s first solo exhibition at New Design was held in 1964 and was comprised of forty watercolours. According to the website Vancouver Art in the Sixties, that show also included a catalogue, Kwakiutl Art, that “was one of the earliest attempts to thoroughly analyze and promote Kwakiutl [sic] Art in print for commercial purposes.”

Speck also exhibited at the Simon Fraser University Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, and his work is included in the collections of the British Columbia Provincial Museum, the Canadian Museum of History, the Glenbow Museum, the San Diego Museum of Man, and the Campbell River Museum.

Duffek explains, however, that Speck’s “work kind of fell out of the public eye after the mid 60s” largely because “he wasn’t part of the exhibits” like Arts of the Raven “that post-mid 1960s really ended up defining Northwest Coast art and bringing it to world attention.”

Famed First Nations artist Bill Reid, for example, didn’t include Speck in the exhibits he organized that were so important in defining that art in the 20th century. Duffek says archival material shows that Reid was “really conflicted” about Speck’s works. “He admired them but he couldn’t place them somehow,” she says.

Yet just because Speck’s works may not have fit into popular 1960s definitions of Northwest Coast art doesn’t mean it’s necessarily outsider art, Rice reiterates.

“I wouldn’t say its outsider art,” Rice says. “Within its context, it’s traditional west-coast art reaching a new pinnacle of contemporary expression.”

Macaulay, for her part, argues that the long-time marginalization and repression of First Nations peoples in Canada could make Speck’s works “outsider” by nature.

“First Nations people have always been marginalized,” Macaulay says. “And I think that we’re all really coming around, particularly with the Truth and Reconciliation process, to think differently about that. But to say that their culture wasn’t alien or marginalized in the context of our dominant culture—well, that’s just not true.”

Macaulay adds that the fact the potlatch ban was lifted just seven or eight years before Speck made many of his paintings underlines the marginalization Speck had to confront during his lifetime.

Rice agrees that the legislation against First Nations cultural practices means that “legally, it’s outsider because it wasn’t allowed to be practiced.” But, he maintains, “to put that label on his style of work—I don’t think it works.”

When asked about the possible problems of applying the outsider art label to Indigenous art, Greg Hill, the National Gallery of Canada’s Audain senior curator, Indigenous art, said via email that “Indigenous art should be seen in as many different contexts as possible.”