For more than 40 years, Detroit-born artist Suzy Lake has been living in Canada, producing groundbreaking work in film, video, performance and photography that is rooted in conceptualism, feminism, and identity and social politics. The last few years have seen a reappraisal of work produced in the early 1970s by women artists, through major exhibitions such as “WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution,” which toured in 2007 and 2008 and included artworks by Lake. In spring 2011, Lake’s early work was reintroduced to Toronto audiences through the Contact Photography Festival, and the artist is currently preparing for her first retrospective, slated for fall 2013 at the Art Gallery of Ontario. In this interview, Bill Clarke meet with Lake at her home studio in Toronto to discuss some of her key works.

Bill Clarke: During your artist’s talk at Georgia Scherman Projects in April 2012, you said that in the 1960s and early 1970s, “We didn’t know who we had become, but we knew what we weren’t.” What did you mean by that?

Suzy Lake: The 1960s and early 1970s were a time of great social change, between civil rights, student movements and the Vietnam War. A lot of us could see cracks in the American Dream, and we knew what we were fighting for—racial and social equality—but when changes started to happen, we didn’t quite know who we had become. I knew that I was no longer the eldest daughter raised simply to become someone’s wife.

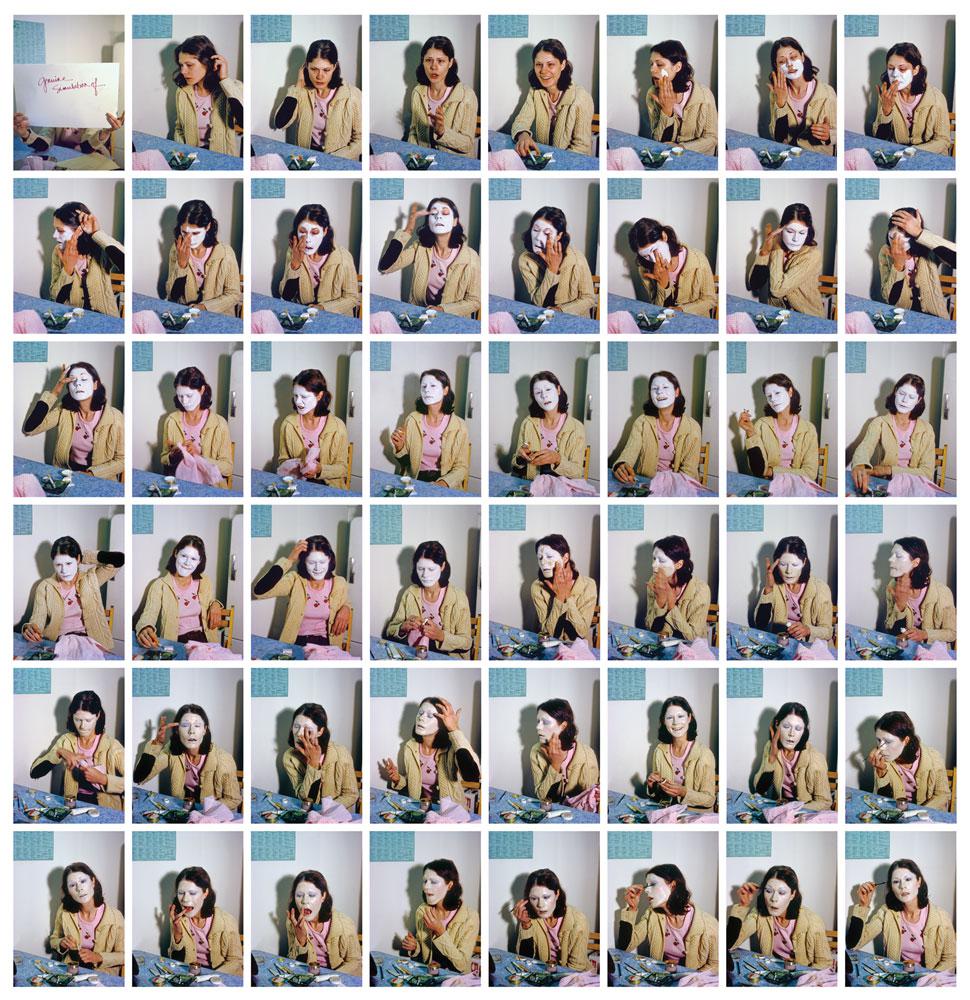

BC: Does a feminist perspective inform a work like A Genuine Simulation of… (1973–74)?

SL: I admired people like Gloria Steinem, but I struggled with being called a feminist artist. I was aware of feminism through my social activism, but, in the early days, I was more concerned with issues of identity and power dynamics, and figuring out where my generation of women was positioning itself. I didn’t realize until later how gendered my early work is. In A Genuine Simulation of…, the whiteface is a tabula rasa and then I use cosmetics to reconstruct an image of myself. Cosmetics can become a mask to hide behind or to advance a desired image. At the time, such work was deemed narcissistic.

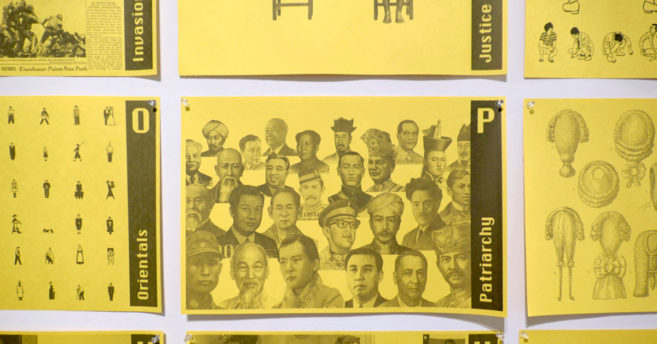

BC: Do some of the works in your Transformation series (1973–74), such as Suzy Lake as Bill Vazan, also address such power dynamics?

SL: Transforming myself into a man allowed me to examine many things, including different strategies of how to make work in a pre-feminist world, but, yes, the images also raise questions about patriarchy. I hope my early work still raises questions about patriarchal influence and serves as a warning to continue to be alert against it.

BC: What prompted you to pick up a camera in the first place?

SL: Photography was a way to document what I considered performances, allowing me to compare the visual qualities of a performance with the content I was trying to convey. For most of the 1970s, when I was living in Montreal, I was considered a conceptual artist, not a photographer. It wasn’t until I moved to Toronto in 1978 that I became more associated with photography.

BC: Has your relationship with some of this older work changed, especially since you are looking at some of it for the first time in years, in preparation for the AGO retrospective?

SL: Looking back at some of this work, I realize now that it was raising questions that even I didn’t realize I was asking! Hindsight has unexpectedly allowed me to see themes in my works and to better understand the period in which they were made. For example, when I was making the performance-photos for Choreographed Puppets (1976–77), I may have been provoked by a dissatisfaction with what was happening in my life at the time, so this work did address the personal for me. But the images of me being manipulated like a puppet speak to the broader idea of struggling against some resistance in society that is trying to control or restrict you.

BC: I think a work like Are You Talking to Me…? (1978–79), which you produced after seeing the film Taxi Driver (1976), also refers to the stress that individuals face because of social pressures or restrictions.

SL: I love that film! Its depiction of Robert De Niro’s character trying to find his place in society and his struggle against the classism of America is brilliant. During the famous “You talkin’ to me?” scene, I felt like he was talking directly to me. I understood some of the performance and filmic strategies that make that scene work, and I wanted to see what struggling with something to the point of letting go would look like in photographs. For this piece, I didn’t check myself emotionally; it was like self-hypnosis.

BC: When I look at your photographs from the 1980s, the themes are the same but the tone seems to change. The images strike me as more violent.

SL: In the 1970s work, I created a psychological dynamic by using my figure almost as a victim. But by the early 1980s, I wanted to convey the idea of having control of one’s own voice, to stop being a victim. These ideas inform the series Pre-Resolution: Using the Ordinances at Hand (1983). The title reflects the moment when you realize that you’re in a powerless position and you must use whatever is at hand to escape from it. My figure, hammering away at the wall, is confined by the physical structure I built around the photo mural. So, it is more about liberation than just “acting out.” It’s an empowered position.

BC: The first work by you I ever saw was called Re-Reading Recovery(1996), in 1997. What was going through your head at this time?

SL: By the late 1990s, I was re-evaluating my position on working with my body. I was no longer that young woman in my early imagery. My perspective on many things had changed. I found that I was quieter, so the work became quieter. Also, I wanted to deal with the aging body as something positive. Experience is positive, maturity is positive, but our culture doesn’t celebrate these attributes when associated with aging.

BC: Especially women aging…

SL: Yes. So, when I made these photographs, I wanted them to be beautiful, to contextualize a positive entry into the work. Although the figure has a sense of history, of some kind of struggle, there’s also a sense of determination. At the time, I felt like I was entering a new stage of life and my career. The images represent ideas around cleaning up and preparing for something new. I was nervous about this work, though. I knew that I wanted to photograph myself in a slip, which would combine the vulnerability with the determination, but I didn’t want it to feel like Cinderella. And our culture is so obsessed with youth culture—would work that talked about aging appeal to anyone?

BC: Did this work’s meaning change for you when it was renamed Rhythm of a True Spaceand displayed on the hoarding around the AGO during its 2008–09 expansion?

SL: The installation at the AGO was an opportunity to push the visual information further. I was interested in emphasizing the figure’s activity by creating a greater rhythm around the floor-sweeping gesture. I don’t think the second iteration denies the reading of the original, but it does carry the performance element further through a perceptual rhythm.

BC: The triptych Beauty at a Proper Distance/In Song (2002) seems to get a strong reaction from people.

SL: It does. From a distance, you think are seeing typical glamour shots, but the closer you get, the more visceral the images become. You see the dried lipstick, the oily skin, the large pores…

BC: The facial hair!

SL: Absolutely! I was wondering what an advertising campaign that tried to make aging women’s facial hair “sexy” would look like. So, I used tropes from that kind of advertising, like the light box and the heightened colour. But really, I get angry when I think about what people do to maintain the illusion of youth while displaying a completely natural aging body is somehow seen as taboo. Beauty is as much a construct as ageism.

BC: I would be shirking my interviewing duties if I did not bring up Cindy Sherman.

SL: First, I should say that what I and other artists like Martha Wilson were doing in the early 1970s felt completely natural, but there was no vocabulary to describe it. We were all working in isolation, and we didn’t have any role models. Cindy was only a few years behind us. Cindy has always given me credit as an influence, even if American art historians choose not to hear her. She’s the reason images of my work appear in the catalogue for her Museum of Modern Art retrospective.

BC: Speaking of retrospectives, how are you finding the experience of planning your own?

SL: Having a real reason to look back is very exciting. I’m seeing my learning process. It is interesting for me to see how my work has evolved, and how the strategies I used when I was younger reappear in later work. I’m rediscovering some of the questions I asked early on and realizing that many are still relevant today. I’ve always liked art that asks questions. When an artwork asks a question, it is, I think, very generous work.

The original version of this article appeared the Winter 2013 issue of Canadian Art. To read more from this issue, please visit its table of contents.