Michelle Furlong

After starting out primarily focused on drawing, Michelle Furlong’s practice turned to sculpture and installation. The Montreal artist’s drawings often feature hands, feet and other body parts in various states of entanglement. A sense of movement is always implied in these compositions, with figures bending and reaching toward their own bodies, adjacent objects and each other. “I wanted to expand these drawings into space,” Furlong says, “and engage the viewer’s body rather than representing a body. I wondered: Can a painting be a sculpture? Can it perform? Can it trigger a sense of movement without itself moving?” This questioning led to works like Weavers Spindle (2017), which consists of large expanses of canvas painted on both sides with collaged imagery of playing cards, suspended from the ceiling via grommets and hiking string. In the process of being hung, the paintings fold and bunch up, gaining depth and three-dimensionality. Furlong describes “punching” them into shape, thus depositing her own body’s movement into the canvases. Wooden staffs topped with billiard-sized balls lean against the nearby walls, giving the impression they might be used to hit the work like a piñata or to participate in this mysterious game room in some other way.

Erica Mendritzki, I’m Hysterical!, 2016. Oil on wood panel, 45.7 x 35.6 cm. Courtesy the artist.

Erica Mendritzki, I’m Hysterical!, 2016. Oil on wood panel, 45.7 x 35.6 cm. Courtesy the artist.

Erica Mendritzki

Erica Mendritzki works at the intersection of painting and sculpture, but not in the sense that her paintings project into three-dimensional space or that she paints on her sculptures. Rather, they tend to occupy the same space, forming a dialogue and sometimes citing one another. Her paintings are simple and ethereal, often implying a body that seems fragile yet alive. Mendritzki recently moved to Halifax but spent the previous six years in Winnipeg, which inspired her 2015 exhibition “SNOWED IN & FELT UP.” Throughout her work, Mendritzki is interested in things that are hard to say, and Winnipeg’s long winters and deep snow cover became a useful metaphor as a shroud for things previously visible. Various found objects scattered across the gallery floor—an antique bedpan, PVC pipe, a neat row of beige UGG boots and an ornamental lawn angel with arms joyfully thrown up—stand in for the accumulated debris that emerges when the snow melts, here charged with psychoanalytic potential. An accompanying suite of small paintings reads like the inner monologues of a sketchbook or diary: a haunting face seems to emerge from mist or smoke above the word “MOTHER”; a reclining Henry Moore nude floats amid the repeatedly scrawled words “Let me talk to you man to man”; what looks like two Post-it notes are each marked with a pleading “Bitte.” It’s a collection of thoughts and emotions concealed and revealed, a gathering of vague daydreams of longing while waiting for a hard winter to end.

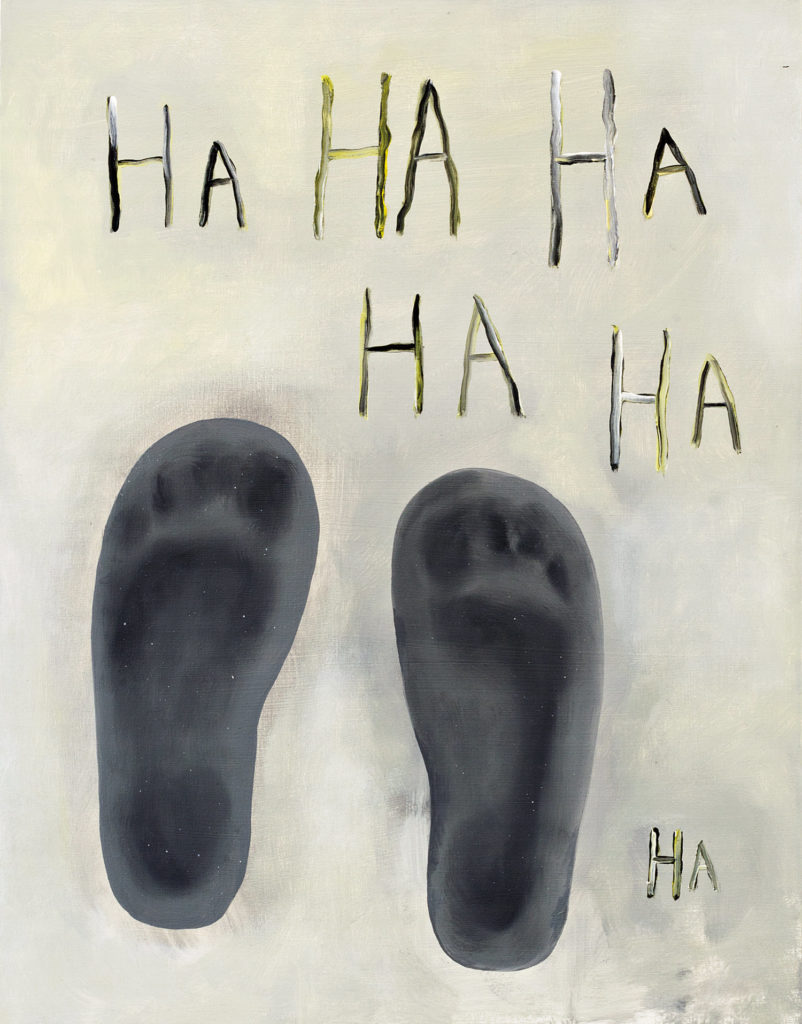

Jane Q Cheng, Study of Expensive Painting (Ship), 2016. Acrylic and oil pastel on canvas, 76.2 x 76.2 cm. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Chris Bentzen.

Jane Q Cheng, Study of Expensive Painting (Ship), 2016. Acrylic and oil pastel on canvas, 76.2 x 76.2 cm. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Chris Bentzen.

Jane Q Cheng

Jane Q Cheng’s practice sometimes demands the creation of paintings, but that is wholly contingent on the artist she’s chosen to imitate. While an undergraduate student at Emily Carr University of Art and Design in Vancouver, where she is based, Cheng joined her classmates in their studios and proceeded to copy exactly what they were making. This practice was magnified when she started copying other appropriation artists, including Turkish American conceptual artist Serkan Özkaya. In Dear Serkan (2018), Cheng sent a series of demanding but polite letters to Özkaya, mimicking the absurd requests he had sent more than a decade earlier to museums and institutions (including a plea to turn the Mona Lisa upside down). She also copied the work of fellow Vancouver artist Andy Dixon, known for his seductive takes on famous Renaissance paintings and luxury brands. After spending some time in Dixon’s studio, Cheng produced a series of copies—both direct and from memory—and predictions of Dixon’s future paintings. Her versions were smaller and included discussions between her and the artist scribbled over the paintings. Dixon has no trouble selling his work, partly because he adopts existing status symbols. Cheng’s copies of his copies sold well too, validating the power of homage while critiquing the art world’s persistent tendency to obsess over a handful of vetted masters.

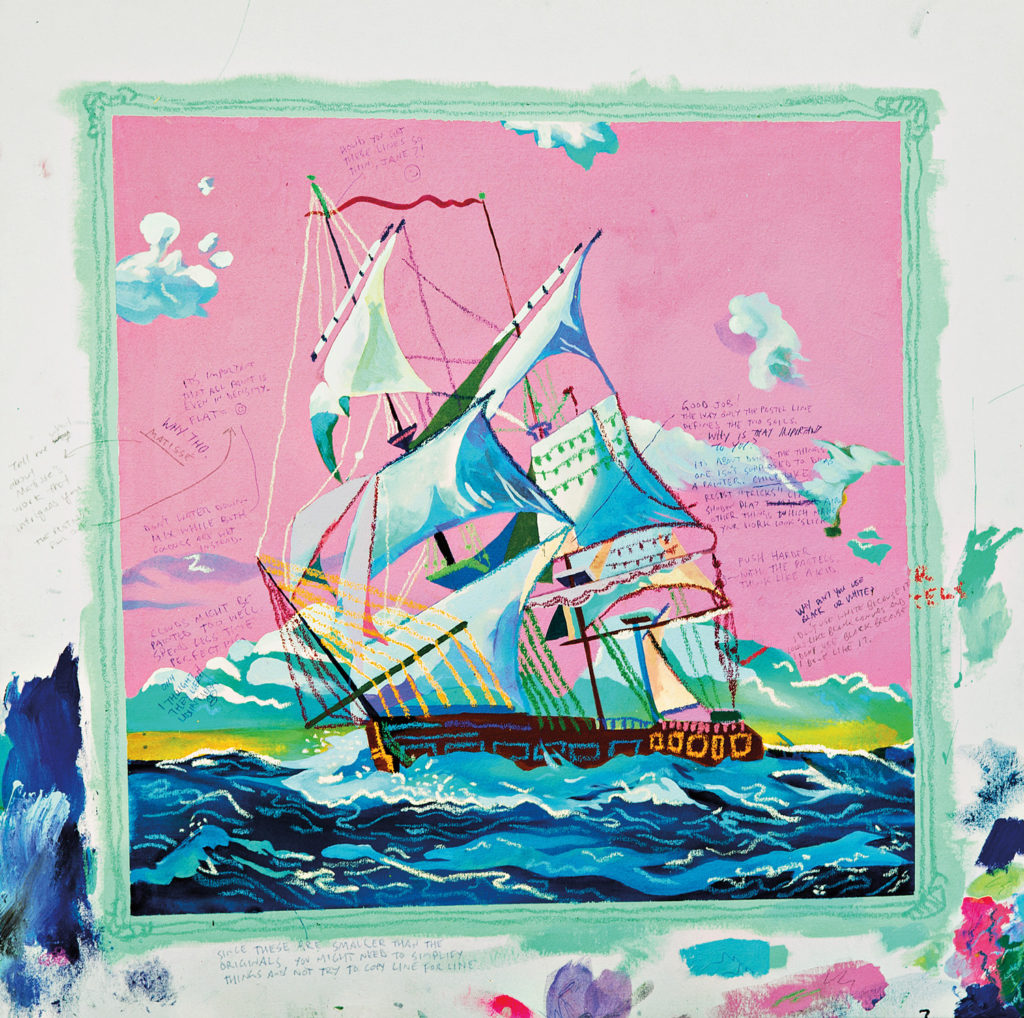

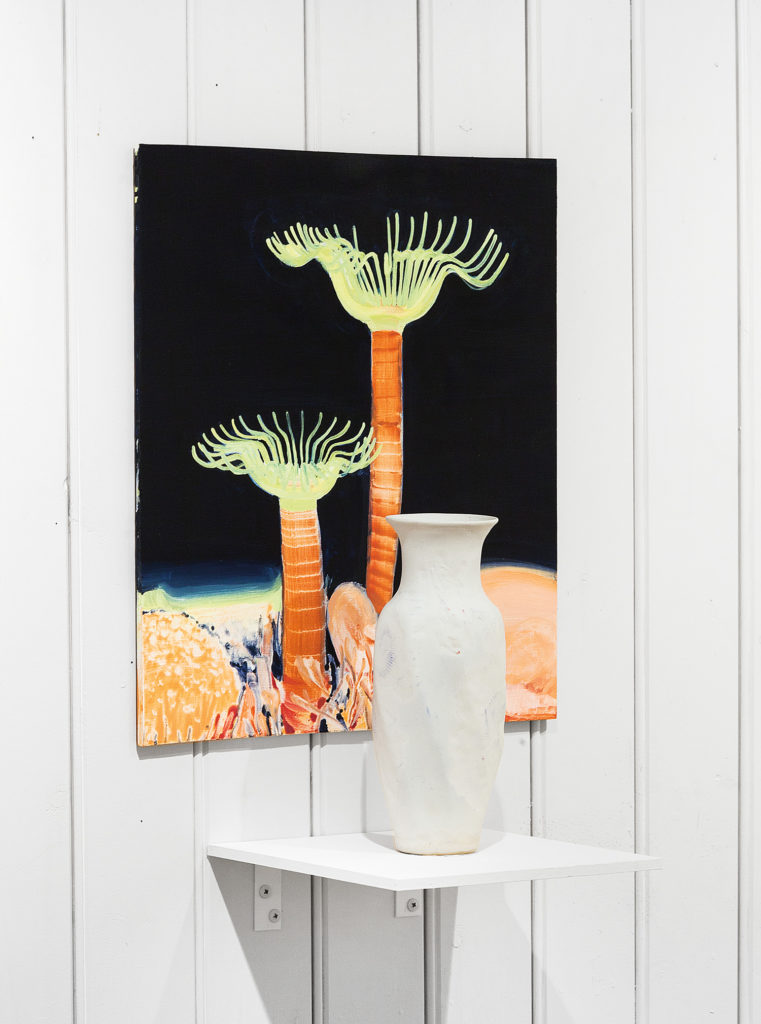

Laura Findlay, Grounds, 2017. Oil on board, shelf and found sandblasted ceramic object, dimensions variable. Courtesy the artist.

Laura Findlay, Grounds, 2017. Oil on board, shelf and found sandblasted ceramic object, dimensions variable. Courtesy the artist.

Laura Findlay

Toronto artist Laura Findlay experiments with translating paintings into three-dimensional space. In her recent exhibition “Echo Location” at Forest City Gallery, small-scale gestural renderings of bats were complemented by Bat Mobile (2018), a sculpture designed according to the shape of the animal’s wing. Silhouetted bat shapes in various colours hung from the mobile’s steel armature, their formation repeating the dispersed arrangement of bat portraits on the gallery walls. Once the kinetic sculpture was set in motion, the viewer’s gaze bounced between the static animal portraits and their moving counterparts, establishing a conceptual push-and-pull between subject and object, form and function. In other exhibitions, Findlay has paired her paintings with found ceramic vases that are partially sandblasted and dipped in gesso. The outer glaze is removed to reveal hidden layers of underglaze, a method that echoes her painting style of wiping into thin washes of wet paint to create tonal range by revealing the white gesso beneath. Enamoured with the relationship between erosion and creation, Findlay demonstrates these primordial forces in delicate terms, with gestures that emphasize material power while appreciating the humble act of representation.

Abby McGuane, Emperor’s Bathtub, 2018. Oil pastel, marble dust, acrylic medium, chalk, soapstone and copper leaf on linen, 1.32 m x 1.52 m. Courtesy the artist/Zalucky Contemporary.

Abby McGuane, Emperor’s Bathtub, 2018. Oil pastel, marble dust, acrylic medium, chalk, soapstone and copper leaf on linen, 1.32 m x 1.52 m. Courtesy the artist/Zalucky Contemporary.

Abby McGuane

The relationship between image and object is central to Toronto artist Abby McGuane’s practice. Working with materials ranging from photographs, found objects and glass to plaster and oil paint, she considers how physical structures influence perception. Windows and their supporting frameworks are of particular interest to her as barriers between public and private spheres that can be seen through, but not often traversed. Reflecting on the idea of invisible but solid barriers, the kinds that prevent women from advancing in the workplace or from leaving dangerous situations, McGuane has interrogated both corporate culture and the sex industry. For the 2018 exhibition “Tableaux Extant” at Zalucky Contemporary, the artist traced the shape of her own body while hovering atop a series of canvases. Railing-like architectural features were painted around and over her silhouette in each painting, referencing the metal frames that hold glass inside VIP booths at strip clubs. “These figure studies are a performance and sculptural act,” she explains, “it’s a trace of the real thing, a snapshot. I think about painting as a sort of ultra thin sculpture in a way, like a skin.” In Figure 5 (2017) we see her body’s outline as a missing shape, hemmed in by the linear, rigid frames and yet unmistakably powerful.

Fin Simonetti, Double Bind, 2017. Hand-carved Portuguese pink marble, 30.5 x 38 x 48.3 cm. Courtesy the artist/Interstate Projects, Brooklyn. Photo: Sebastian Bach.

Fin Simonetti, Double Bind, 2017. Hand-carved Portuguese pink marble, 30.5 x 38 x 48.3 cm. Courtesy the artist/Interstate Projects, Brooklyn. Photo: Sebastian Bach.

Fin Simonetti

Since training as a figurative painter, Vancouver-born, New York–based artist Fin Simonetti has branched out to work with sculpture, installation and drawing to investigate visual tropes of security and masculinity. Representations of animals, particularly dogs, recur in her practice as markers of more generalized social violence and domination. Pastoral Emergency (2018) belongs to a suite of intricate drawings in red ballpoint pen. It depicts hunting dogs embroiled in a mysterious scene with a throng of underdressed young women. Even more alluring are Simonetti’s rose-coloured marble sculptures of pit-bull heads. Carved with extraordinary realism using a hammer and chisel, the dog heads appear tender and vulnerable on account of their pink-and-white colouration and defenseless state. The dog in Double Bind (2017) is especially forlorn, with tattered ears and a muzzle. Simonetti is interested in this breed as a social signifier of physical power, a body that is weaponized through particular kinds of treatment. By eliciting empathy for these potentially dangerous creatures, the artist suggests that social expectations shape, and even create, individual aggression and fear.

Amanda Boulos, Can’t Sea, Eye Exercises For Artists (still), 2018. Video, 4 minutes 26 seconds. Courtesy the artist.

Amanda Boulos, Can’t Sea, Eye Exercises For Artists (still), 2018. Video, 4 minutes 26 seconds. Courtesy the artist.

Amanda Boulos

Amanda Boulos is primarily known for her paintings. Built up using countless layers of transparent oil glazes, her canvases appear detailed and intimate due to both a laborious process and a repertoire of symbols drawn from her family history. Based in Toronto, Boulos was born in Canada to a family displaced by the 1948 war in Palestine and the subsequent Lebanese Civil War. Stories about “back home,” a place temporally and politically inaccessible, motivate her recurring motifs of the eye and candle. “I am interested in the notion of vision and privilege,” Boulos explains, “because during the war my parents were hiding in basements. They were always gambling with going outside to see what was happening above ground.” In her captivating though lesser-known videos, Boulos takes up a strikingly different stylistic approach by exploiting the blurry, low-fi quality of found footage. Although she does not know most of the people in her videos, Boulos thinks of them as stand-ins for her own family. In Can’t Sea, Eye Exercises For Artists (2018), a man demonstrates exercises to strengthen eyesight by holding his thumb against the horizon and switching focus between his digit and the mountain range in the distance. The video cuts to a woman doing eye exercises of her own by looking far left, then right, then up and down. Enigmatic and slightly absurd, the work emphasizes the importance of sight in a world governed by knowledge and information.

Marlon Kroll, Blooming Planes, 2019. Coloured pencil on muslin over panel, glazed ceramic. Dimensions variable. Courtesy the artist/Clint Roenisch. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Marlon Kroll, Blooming Planes, 2019. Coloured pencil on muslin over panel, glazed ceramic. Dimensions variable. Courtesy the artist/Clint Roenisch. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Marlon Kroll

Montreal artist Marlon Kroll has a knack for making even the most traditional forms, like ceramics and drawing, seem unusual. Kroll’s sculptural works often take the form of objects carefully arranged in a tidy mess across gallery floors and walls. You find everything from glazed stoneware, strips of pine, Ziploc bags, alligator clips and found cabinet doors, to folded prints and stacked drawings in coloured pencil on muslin or an old bed sheet. His dominant theme is the nature of inanimate relationships. How a metal pipe rests delicately on a piece of wood or a winding piece of clay echoes the bend in another material is of critical importance. “I’m working with associations, and with the form of things,” Kroll explains. “There is a give and take between me and the materials, what the objects already are.” Kroll’s signature clay works, often balanced upon or hung from his drawings, resemble snakes, pretzels or large bangle bracelets pressed with a succession of oval-shaped imprints. The human body and its impact is everywhere in his work. Particularly evocative is Memories (2016), a print on artificial suede depicting pinkish folds of flesh that dominate the frame. It is impossible to tell which part of the body is depicted, but the effect of cropping and repeating produces a sense of tenderness and empathy for the soft human body, heightened by the suede’s downy texture.

Sean Ross Stewart, The Shirt Off My Back, 2019. Steel, shirt and dried flora, 41 x 31 x 4 cm. Courtesy the artist/Crutch CAC. Photo: Grayson James.

Sean Ross Stewart, The Shirt Off My Back, 2019. Steel, shirt and dried flora, 41 x 31 x 4 cm. Courtesy the artist/Crutch CAC. Photo: Grayson James.

Sean Ross Stewart

Sean Ross Stewart’s recent production involves integrating many artistic mediums to create immersive environments. His drawings and paintings are frequently joined by sound pieces and sculptural installations, giving the two-dimensional works a rich context and expanding their range of meaning. His recent exhibition “A Worker’s Pantry” at Crutch CAC in Toronto featured a custom-built room occupying almost the entire gallery. Constructed of hot-rolled steel sheets, Stewart’s Chamber No. 1 (2019) contains sculptures, drawings and paintings made of combinations of organic and manufactured materials—bird seed, charcoal, a tree branch, a bird’s nest, a chair, a pair of shoes. A drone-like composition filled the air in the gallery space. Entering the enclosure was a bit like finding an abandoned shack in the woods. Stewart is based in Toronto but grew up in Burlington and Hamilton, and describes Canada’s “steel capital” as an influence. “I’ve been using a lot of steel to reflect on Hamilton’s mix of industrial and recreational areas,” Stewart notes. “The places we played soccer had this long, overgrown grass, but also trash all around. Garbage is always washing up on the beaches, dead seagulls set against massive factories. There is glaring tension between industry and the ecosystem there.” Hanging on the enclosure’s metallic walls, A Reminder (2019) consists of quail-egg shells and a handwritten note, framed and attached to a ground of painted steel. “A cloud of dust still hovers in the air,” the note reads—a cautionary echo all too familiar to industry towns and their fallout.

Katrina Marie Mendoza, Kawawa Window & Door, 2014. Vinyl, 3D prints, artificial turf,

carpet underlay, wood and light, dimensions variable. Courtesy the artist.

Katrina Marie Mendoza, Kawawa Window & Door, 2014. Vinyl, 3D prints, artificial turf,

carpet underlay, wood and light, dimensions variable. Courtesy the artist.

Katrina Marie Mendoza

At a glance, Katrina Marie Mendoza’s works look like peculiar architectural drafts laced with a secret language. A cast of abstract squiggles and vague letterforms populate her drawings, sculptures and installations, reflecting her interest in asemic writing (wordless text without semantic meaning). Based in Winnipeg, Mendoza initially learned to draw and paint, then went on to study digital drafting. Her letterforms and “diagrams” are typically created in a vector drawing program and laser cut into plastic, 3D-printed or printed on fabric. Mendoza refers to her practice as “collage in 3D” and reassembles the same repertoire of shapes across different exhibitions. Creating space for observers to form their own interpretations is key. “I’m into forms and scenes that are trying to be real things but don’t end up being those things,” Mendoza explains. “I like partially not knowing what something is, like when writing becomes objects and nobody knows where they came from or what they are used for.” Features that both provide and deny access, such as windows, doors and blinds, recur in her practice, often presented as enigmatically as her invented language.

Michelle Furlong, Weavers Spindle, 2017. Oil, grommet and rope on canvas, 1.8 m x 2.2 m x 91.4 cm. Courtesy the artist/Parisian Laundry. Photo: Elise Windsor.

Michelle Furlong, Weavers Spindle, 2017. Oil, grommet and rope on canvas, 1.8 m x 2.2 m x 91.4 cm. Courtesy the artist/Parisian Laundry. Photo: Elise Windsor.