Walk or drive around any major North American city these days and it’s hard to miss the signs that pot is on the rise.

In recent months, billboards for Weedmaps—the website and app that promises “the most reliable online resource to find cannabis storefronts, doctors and deals,” a kind of Yelp for pot—have been installed on highways and subway platforms from Toronto to New Orleans and from Phoenix to Vancouver. At sidewalk level, storefront dispensaries have grown tenfold in some Canadian cities in little over a year. And public video screens displaying 24-hour news stations have, in recent weeks, featured footage of people like former Toronto police chief (and current Scarborough-area MP) Bill Blair proclaiming that the Trudeau government’s pot legalization efforts will make Canada safer for children.

And pot isn’t just more visible on the streets. It’s also, increasingly, crossing over into the physical and conceptual spaces of contemporary art.

This spring, the Penticton Art Gallery is hosting “#Grassland”—what it believes is Canada’s first public-gallery art exhibition focused on marijuana.

In Toronto, the rapidly expanding pot-retail outfit Tokyo Smoke is leveraging high-art aesthetics and practitioners to rebrand the weed experience. Strategies include commissioning artists to do murals for its coffeeshop outlets and to produce projects for its new highbrow magazine—as well as design minimalist pipes and bongs.

Glassware is also emerging as a sculptural trend. The white-cube space Apexart in New York is currently hosting an exhibition of traditionally psychedelic pipes and paraphernalia, while contemporary artists like Elias Hansen— currently showing in Toronto—integrate explicit references to drug culture in their glass artworks.

And last but certainly not least: as cannabis culture becomes more visible in the mainstream, some contemporary artists in Canada are directly referencing that trend to explore themes of memory, narrative, place and consumerism.

Could all this be yet another instance, as Randi Bergman has written, of art simply following fashion? After all, weed prints have been a thing on the runway since at least 2015, and Rihanna has long been an icon of sweet-leaf style. Kim Kardashian was Insta’d last fall in an Alexander Wang pot-leaf dress. And more recently, Juergen Teller (the fashion-friendly fine-art photog represented by Lehmann Maupin Gallery) made photos in a 60,000-square-foot medical marijuana grow-op in Canada—a shoot commissioned by System mag.

Or could the weed-art trend signal something more than fashion? Are there other reasons why Stefan Benchoam’s cactus studded with half-smoked joints was deemed one of the best sculptures at NADA Miami a few months ago? Could a massive public-art sculpture of rainbow-coloured bud really be coming soon to a plaza or park in a Canadian city?

Here, we sample some of the buzz on this phenomenon.

Toronto-based pot brand Tokyo Smoke says it is trying to reimagine the visual language around weed. It recently launched this new pipe-design collaboration with Partisans, an award-winning creative studio in Toronto. Photo: Courtesy Tokyo Smoke.

Toronto-based pot brand Tokyo Smoke says it is trying to reimagine the visual language around weed. It recently launched this new pipe-design collaboration with Partisans, an award-winning creative studio in Toronto. Photo: Courtesy Tokyo Smoke.

The Artful Dispensary

Tokyo Smoke, a relatively new retail chain for pot and pot accessories based in Toronto, has made very conscious use of modern and contemporary art—and related curatorial strategies—in its branding and visuals.

The aim, says creative director Berkeley Poole, is to create a new visual language for weed culture—one that is more approachable to families, older people and other markets less friendly to the grittier, more traditional head-shop environment.

“I think bringing a design sensibility to these products makes them a lot more approachable to a lot of people,” says Poole, a former art director for Barneys New York and also currently creative director of Adult Magazine. “It’s all wrapped up in creating a new language for this product, one that is more experiential and emotional.”

Tokyo Smoke’s Instagram feed, for instance, features posts of elegant, minimal works by none other Tauba Auerbach, Marcel Duchamp and Piet Mondrian. A few years ago, in Toronto, the company co-presented its own white-cube exhibition featuring Andreas Gursky–style photographs of a medical-cannabis grow-op, and it also sold related prints on the Tokyo Smoke website.

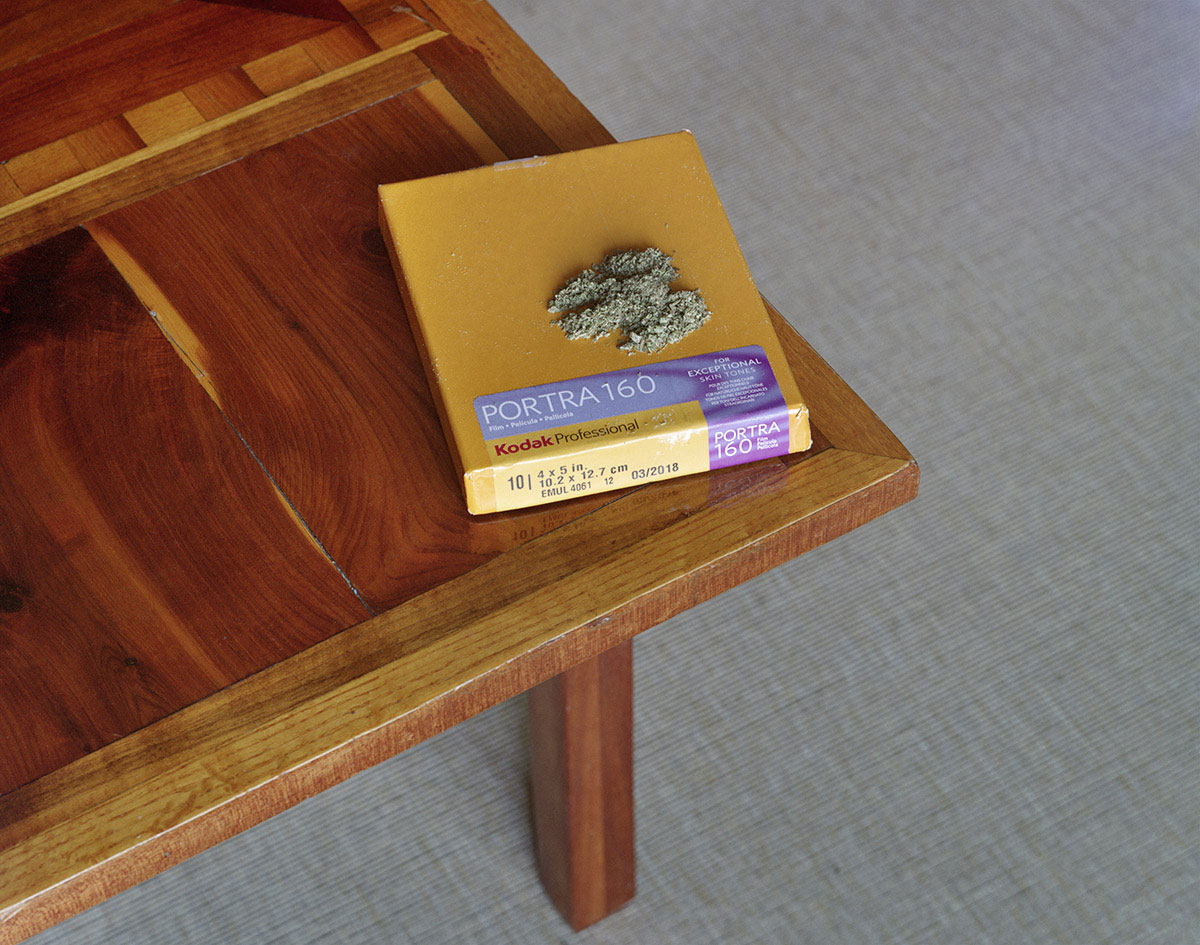

Poole also names artists Wolfgang Tillmans and Vivianne Sassen as some of the key mood-board influences for Tokyo Smoke’s arty new magazine, Hi (first issue out today, for 4/20). Inside the pages of the new mag is a project by Toronto photographer Maya Fuhr (who lists none other than Jeff Koons and Cicciolina under her “Artist Collaboration” page) in which some of Fuhr’s peers analyze or respond to Fuhr’s abstract photo-prints after smoking up—a kind of altered-states art-crit project.

“I’ve talked to so many people who really like to enjoy smoking when they have a creative task at hand,” says Poole. “I think it helps get them into a different mindset where trivial worries go away and they can focus on creative pursuits.”

Accordingly, some of the back-of-book mini-profiles in Hi also emphasize the role of pot-smoking in the creative process.

“I usually like to be alone [when I smoke], unless I’m with people that have a similar creative drive,” states a man only identified as Eric. “I really continue adding to my vision, drawing, creating on rhino (3D designing program). Or playing with material. I’ve been really into transparency lately so I’ve been playing with light and different types of acrylics. I also like sculpting my designs after I draw them (when I’m high usually), I usually use clay and then vacuum form it right after. I basically just want to chill in a studio.”

Tokyo Smoke also commissions artists to make murals or other collaborative works for each of its shops. The one in Toronto is painted by Brazilian graffiti artist Alex Senna, and another (artist to be announced) is due for the shop’s coming expansion into Seattle’s Thomson Hotel.

Some of the outlets have also featured artworks by senior Canadian artist John Scott, among others. These pieces are pulled from the personal art collection of Alan and Lorne Gertner, the father-son duo behind Tokyo Smoke.

Not surprisingly, perhaps, the elder Gertner, Lorne, is a fan of art and design in this and other fields. Besides investing early in the medical-cannabis industry by co-founding Cannasat Therapeutics in 2004, he initially trained in architecture and is on the board of the Design Exchange. Lorne Gertner also first cut his teeth in retail with Mister Leonard, the women’s clothing label he inherited from his father.

“As things become commoditized, then brands and design becomes important,” Lorne Gertner recently told Canadian Business.

Architecture, art and design, and pot also merge in some of the specially commissioned pipes and bongs Tokyo Smoke has brought on board. The latest one is by Partisans, an award-winning creative studio in Toronto known, in part, for its revitalization of Union Station and its Gaudi-esque interior design for Bar Raval.

“I see this disparity in the industry between hippie aesthetics and dispensaries that are very sterile, like an IKEA showroom,” says Poole. “We are really developing a visual language that hasn’t been there before.”

Tokyo Smoke isn’t the only weed retailer trying to make over the drug in a contemporary-art, curatorial-approach vein—the strains of pot offered by Tweed have been similarly renamed and repackaged, spa-apothecary style.

It’s no doubt something we will see more of, as weed has been identified as one of the next big luxury goods. And what good is more luxury-identified (besides fashion, perhaps) than high art?

A detail of Elias Hansen’s installation work It ain’t what it seem (2012–2017) at Cooper Cole in Toronto. The work contains many glass forms, some of which evoke beer bottles, bongs and lab ware. Photo: Courtesy the artist and Cooper Cole.

A detail of Elias Hansen’s installation work It ain’t what it seem (2012–2017) at Cooper Cole in Toronto. The work contains many glass forms, some of which evoke beer bottles, bongs and lab ware. Photo: Courtesy the artist and Cooper Cole.

Glassware as Sculpture

Yet while Tokyo Smoke and its brethren are making the (implicit) case that a mostly maximalist weed culture could use a minimalist contemporary-art makeover, an exhibition in New York seems to be asking what contemporary art (and the mainstream, for that matter) could learn from the traditional visual culture of pot.

The exhibition “Outlaw Glass,” currently on at long-time non-profit space Apexart, brings together glassware by 50 makers across North America.

“The hottest hot take seems to be ‘marijuana is going mainstream,’ an analysis that snobbishly presumes this cultural exchange will be a one-way street,” writes exhibition curator, Vice contributor and former High Times editor David Bienenstock in a related essay. “So to better understand what authentic underground cannabis culture has to offer, Outlaw Glass examines work from leading ‘functional’ glass artists and traces the history of this legally grey art form.”

“Outlaw Glass” pays homage in particular to Bob Snodgrass, a maker of pipes and bongs who innovated certain techniques in the field, and shared them with other makers.

“The technical quality of the work and the enthusiasm around the scene are really impressive,” says Bienenstock in an interview. (He also points out functional pipes and such are generally more affordable, and thus perhaps more popular, than gallery-sold sculptures.)

Bienenstock also shoots down the notion that traditional weed culture is visually “lame,” as Tokyo Smoke’s Berkeley Poole has opined. Instead, he suggests, there’s a (sub)cultural difference at hand.

“I don’t think you would look at the aesthetic of a geographically distant culture and expect it to conform to some of those minimalist ideas,” Bienenstock says. “You would want to take the works on their own terms, and understand why they are exciting or important to the people who represent that culture. I think they should look at these objects in the same way.”

Presented in the white-cube space, in glossy, mirrored display cases, these largely functional objects do, indeed, seem to read more as small-scale sculpture than as drug paraphernalia.

In fact, one of Toronto’s leading young dealers says that glass could be the next big materials trend in contemporary art.

“I do feel like glass is having a bit of a moment,” says Simon Cole, director/curator of Cooper Cole. “Much like you may have seen ceramic artists [more] in the last couple of years” in contemporary art, or textile artists, for that matter, Cole thinks “viewers are becoming more open to different ideas of what is considered art.”

This trend is certainly on evidence at Cole’s own gallery, where American artist Elias Hansen has created installations that include much glass sculpture. Some of Hansen’s sculptural forms directly reference beer bottles, while others may read as bongs or drug-lab ware. Titles of some of his past exhibitions directly reference drug culture as well, like his 2010 Lawrimore Projects show “We Used to Get So High.”

“Eli is from the Pacific Northwest, and grew up just outside of Seattle in a very arts-based community,” says Cole. “His parents bound books for a living, and that area has a huge history in glasswork…. Before Eli started exhibiting in a white-cube fine-art context, he was working in glass as a craft.”

Cole does note, however, that although these sculptures are “definitely rooted in familiar glass objects such as a bong or something of that nature,” none of Hansen’s sculptures are functional—“even the beer bottle has a hole in it,” Cole says.

Graeme Wahn is a Vancouver photographer; his large 48″ x 36″ print ssssuuurrrrrffffaaaccccceeee is part of “#Grassland” at the Penticton Art Gallery. Courtesy the artist.

Graeme Wahn is a Vancouver photographer; his large 48″ x 36″ print ssssuuurrrrrffffaaaccccceeee is part of “#Grassland” at the Penticton Art Gallery. Courtesy the artist.

Curating Around the Cannabis-Culture Buzz

Paul Crawford, curator at the Penticton Art Gallery, likes to think of his exhibitions as being responsive to current events—and as helping to shed light on these events for the gallery’s audiences.

A couple of years ago, for instance, Crawford put together an exhibition on art in Afghanistan for the PAG. Last year, he organized an exhibition on contemporary Syrian art.

And this spring, it’s all about “#Grassland”—an exhibition that he and the gallery have billed as Canada’s first public-gallery art show about pot.

But while “#Grassland” certainly is timely given the Trudeau government’s announcements these past few weeks on cannabis legalization, it’s something that Crawford has been thinking about for more than a decade.

Before Crawford lived in Penticton, he was based in Grand Forks, in the Kootenays.

“I’d always known about cannabis culture, but moving to the Kootenays was the first time it became part of the fabric of the community I lived in,” Crawford recalls of his time in Grand Forks. “I was curious about the tacit complicity everyone seemed to have towards the industry, including the RCMP.”

The complexity of mainstream Canadian culture’s relationship to pot was also underlined to Crawford more recently, when he found out that local pipe-and-bong-maker Patrick “Redbeard” Vrolyk had won the 2015 Visual Artist Prize from the Penticton Arts Council.

“I was fascinated that our conservative town here would award a guy making bongs the artist-of-the-year award,” says Crawford. “It also made me look at something I’d never considered high art—just that piece of glass sitting on my friend’s coffee table. It was a fascinating thing to delve into that whole world.”

Wanting to plumb the complicated nature of cannabis in Canada’s public sphere, Crawford initially started curating “#Grassland” by collecting newspaper-editorial cartoons from across Canada about the issue. (Among them is Theo Moudakis’ iconic “Marijuanada.”) He also had it in mind to include Vrolyk’s award-winning glasswork, which is presented in a collary solo exhibition.

Then, he contacted some major artists who have worked with the theme, like New York’s Bentley Meeker. Known in part for creating chandeliers out of bongs, and known in part as a commercial lighting designer, Meeker created a projected-light work called Weed World for the Penticton exhibition. Another international artist, Brazil’s Fernando de la Rocque, sent in a text work from his well-established Blow Job series—works created out of bong smoke on cloth. The one in “#Grassland” reads “Stop Drug Wars.”

Other artworks came in for submission as Crawford started to do media interviews about the show. Among these was Vancouver photographer Graeme Wahn’s large-scale light-jet print ssssuuurrrrrffffaaaccccceeee.

The result is that “#Grassland” has a mix of works, from professional to amateur. But for the most part they have one thing in common: they are pro-cannabis. And that posed a bit of a problem for Crawford, given his curatorial intent.

“One thing I wanted to do was have a balanced viewpoint,” says Crawford. “Even though I am pro-cannabis myself, I tried to find anti-cannabis art—and there isn’t any. Or none that I could find.”

Crawford is hoping that a more balanced perspective on cannabis can come from programming around the show—like a panel on the legality of pot with local city councillors and lawyers, and another panel with mental-health professionals. (Though pot is often promoted as an aid to those experiencing depression and anxiety, the Canadian Psychiatric Association recently issued a release stating its concern about the link between pot-smoking and schizophrenia-related psychosis, particularly in those under the age of 25.)

Crawford says some of the works in the show—like tribute posters to legalization activist and dispensary owner Marc Emery—have demonstrated to him the dedication of the activist community around pot. But he wonders who will really benefit when weed is legalized.

“Those guys have done the time, paid the fines, taken the hits, and the guys in the suits are coming behind to make all the money off of this,” Crawford says.

Vancouver artist Myfanwy MacLeod originally made this installation out of a 3-D printed marijuana bud and a magazine cutout, calling it Sweet Maryjane (2015). A friend later suggested Déjeuner sur l’herbe would be a better title; MacLeod agrees, and also says she would love to make the sculpture into a large-scale public art piece someday. Courtesy the artist and Catriona Jeffries.

Vancouver artist Myfanwy MacLeod originally made this installation out of a 3-D printed marijuana bud and a magazine cutout, calling it Sweet Maryjane (2015). A friend later suggested Déjeuner sur l’herbe would be a better title; MacLeod agrees, and also says she would love to make the sculpture into a large-scale public art piece someday. Courtesy the artist and Catriona Jeffries.

Artists Stir Up Pot’s Relationship to Gender and Place

Just as Paul Crawford is, as a curator, hoping to address some of the downsides of pot’s rise through his programming, some contemporary artists have been working through the complexity of the pot narrative in other ways.

Vancouver artist Myfanwy MacLeod, for instance, made an entire suite of works in 2014 called Albert Walker—a phrase that denotes both a particular strain of weed and an individual from MacLeod’s home region of Southern Ontario who was a known murderer and embezzler.

“The Albert Walker is a specific type of clone [of marijuana plant], and because he was an identity thief and an embezzler, the idea that the plant was a clone was interesting to me,” MacLeod says. Riffing on this cloning theme, her installation work of the same title features a dozen 3D-printed replicas of marijuana buds.

The many treads of fantasy and grittiness intertwined in pot culture are also something MacLeod has explored. Some of her works on paper include drawings of marijuana buds titled Asian Fantasy and London Supreme, while her 2006 show “Where I Lived and What I Lived For,” at the Contemporary Art Gallery featured drawings of moldy and decrepit grow-op interiors.

“There was this weird book I bought called The Cannabible,” MacLeod recalls, ”and it has all these different strains with romantic names—like, Scheherazade and Luke Skywalker.”

This romance was held in tension with the messy realities of growing pot.

“I had seen some images in an article about grow-ops, and I was interested in what happens with a grow-op house architecturally,” says MacLeod. It also reminded her of moonshining, another process the artist has made art about, as well as houses on the grounds of Glenfiddich’s distillery, where she was doing a residency in the mid-2000s.

From another angle, MacLeod—influenced by the writings in Michael Pollan’s book The Botany of Desire—is also interested in pot as a “tool for forgetting.”

“Pollan talks about our ability to forget things being a really important factor in our being able to stay sane,” MacLeod notes.

In her work, this tendency is contrasted with personal memories of growing up in London, Ontario, in the 1970s, when many young men grew pot in their backyards—a practice that, along with fixing up muscle cars and listening to Led Zeppelin, was cultivated as a sign of masculinity. It’s no mistake that Macleod’s The Jet Set, part of a suite drawing on those memories of London, directly references weed culture and its gender roles.

“In the 1950s and 60s, it was more about alcohol—the Mad Men excessive drinking thing. During prohibition, writers like Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald used it as a sign of masculinity and virility,” MacLeod observes. “In the 1970s, that shifts into marijuana, and all those ridiculous books like Carlos Castenada and Aldous Huxley and Herman Hesse—a different way of understanding consciousness.”

And even if pot is largely about forgetting according to Pollan, MacLeod hopes to one day engage in the slippery exercise of making pot concrete in public memory—namely, by creating a massive public-art sculpture of a rainbow-coloured marijuana bud.

“I’ve always wanted to make that as a public-art piece,” says MacLeod, who has created a small-scale work of that type, as well as large-scale sculptures of sparrows in Vancouver. “It’s quite an organic shape.”

Scott Kemp, another artist based in Vancouver, is interested in manifesting ideas about pot and public space in yet another way.

In his fall 2016 exhibition at Duplex titled “Master and Apprentice, Lobster and Leaf,” Kemp created a 10-foot-tall wall drawing of a cartoon-like pot-leaf character, as well as a small, colourful figurine of an anthropomorphized pot leaf.

“There is this huge spike of visibility of imagery regarding the drug” with the explosion in dispensaries in Vancouver, Kemp says, “and there’s a whole bunch of different types of stores, and a lot of different types of branding. I was interested in that show in looking at the imagery and how it is a reflection of where we are culturally in this city specifically, as a reflection of the place where we are at.”

By putting the pot-leaf imagery in dialogue with lobster imagery, Kemp also hoped to suggest other historical trajectories in which the abject has become an object of (luxury) desire.

“The image of the lobster as a consumable project has gone on a similar path in general public opinion,” says Kemp. “It was first considered a peasant food, but people’s perceptions have changed.”

In Kemp’s opinion, like MacLeod’s, pot is a complex topic, with many levels of representation to engage.

So perhaps the only real problem with making contemporary art about weed, then, is the shallowness and jokiness with which these deeper narratives and nuances are often glossed.

“It’s a tough subject to work with,” Kemp says. “When I was putting the show together and talking about it, it was hard to move the conversation outside of jokes. It seems really stuck in Cheech-and-Chong-land.”

Leah Sandals is managing editor, online, at Canadian Art.

This article was clarified on April 20, 2017. The original stated that Maya Fuhr has collaborated with Jeff Koons and Cicciolina. This was clarified to read that Jeff Koons and Cicciolina artists are listed under Fuhr’s Artist Collaborations on her website.

Bentley Meeker's Weed World (2016) is an immersive lighting installation that is part of ”#Grassland” at the Penticton Art Gallery. The New York artist and lighting designer is also known for his “bongoliers,” or chandeliers made out of bongs. Photo: Stephanie Seaton.

Bentley Meeker's Weed World (2016) is an immersive lighting installation that is part of ”#Grassland” at the Penticton Art Gallery. The New York artist and lighting designer is also known for his “bongoliers,” or chandeliers made out of bongs. Photo: Stephanie Seaton.