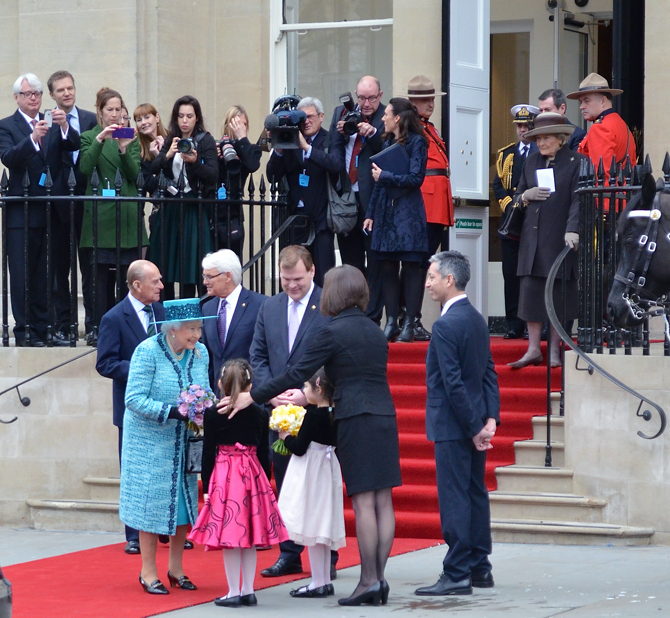

A month ago in London, the traffic in front of the Trafalgar Square entrance to Canada House, the home of the High Commission of Canada and Canada’s diplomatic presence in the UK, was stopped, briefly, as a deep burgundy Bentley State Limousine topped with a crest and pennant featuring the Royal Standard rounded the corner and pulled up. A reception line that included the High Commissioner, Gordon Campbell, and former Minister of Foreign Affairs, John Baird, stood to greet Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II and the Duke of Edinburgh as they stepped out of their car and onto the red carpet.

It was the royal “ribbon cutting” event celebrating the revitalization of Canada House—a project that, in effect, had three outcomes: the consolidation of Canadian diplomatic services in the UK (MacDonald House in Grosvenor Square was sold and a building adjacent to Canada House on Pall Mall East was purchased and integrated into the existing Canada House); the expansion and renovation of the new Canada House; and the rebuilding and rebranding of Canadian identity itself through art, design, architecture, social media and public engagement.

The project raises a perennial question: How can Canadian identity be represented, or rebranded, without resorting to clichés about hockey and maple syrup? How can this country’s geographic expanses and diverse and distinct geographical, cultural and historical complexities be accounted for? It became apparent when touring Canada House that, if the building is a microcosm of Canada, it is through the cultural production of Canadian artists, designers and craftspeople that the nation’s nuance and breath is communicated.

In the afternoon following the ribbon cutting, 200 or more guests—including diplomats, politicians, Canadian and British arts professionals (Ian Wallace, Kathleen Ritter and Ian Dejardin among them)—attended the official opening reception, along with the customary Mounties in full uniform. Caterers dressed in achromatic black served champagne and Canada-themed hors d’oeuvres such as miniature Nanaimo bars and candied smoked salmon. The High Commissioner kept his opening remarks to an equally minimalist “Enjoy yourselves!” as the building was opened to the guests.

The new Canada House structures Canadian identity via themed rooms: one for each of the ten provinces, three territories and three oceans, with an additional four rooms named after prime ministers (Sir John A. Macdonald; Sir Wilfrid Laurier; Sir Robert Borden and William Lyon Mackenzie King). Each room is proportionally sized according to the population of each region (no, the Prince Edward Island Room is not a broom closet—both it and the Newfoundland and Labrador Room are, admittedly, very small meeting spaces, but nonetheless gorgeous representations). All the rooms are furnished with regional art, fine craft and design. Indigenous wood from various parts of Canada is a motif that runs throughout the architectural design, representing Canada’s roots (both at home and in the UK) and new growth.

During the opening, Simon Anderson, the High Commission’s public programs officer, toured me through the building, offering background information on furnishings and pointing out features like the deck—a contemporary structure extended off the roof in anticipation of a “Beehive Hotel” sponsored by the Savoy Hotel (part of a larger program encouraging urban-bee colonies by placing hives on hotel roof tops throughout North America).

The display of work throughout Canada House is not atypical—all Canadian embassies or high commissions contain examples of domestic art. Occasionally pieces are moved from one diplomatic mission to another, as with Marlene Creates’s photographs in the Newfoundland and Labrador room of Canada House, which were previously in Oslo. While art is a feature of diplomatic buildings, none rival the collection on view in Canada House, which is the largest and most public.

A day after the opening events, Canada House Gallery had its inaugural exhibition reception for “Jeff Wall: Five Pictures in a Gallery.” The gallery is a section of Canada House that the public can access without appointment or special arrangement. Comprised of five large-scale photographs by Wall, The Pine on the Corner (1990), A woman consulting a catalogue (2005), Figures on a sidewalk (2008), Intersection (2008) and Boy falls from tree (2010), the exhibition was attended by several Canadians including Ritter, Wallace, Risa Horowitz, Andrew Wright, Lisa Baldissera, Noel and Barbara Best, Wall, of course, and others. There was more champagne, more hors d’oeuvres, more catering staff dressed in black. After the reception, guests were led to the Mackenzie Room, a grand, multipurpose space, where Wall spoke about his art practice in general.

With more than 200 works of Canadian contemporary and historical art, design and fine craft displayed and thoughtfully integrated into the architecture at Canada House, the value that Canadian art and cultural producers offer, and their contribution to Canadian identity, is made resoundingly clear.