Generously supported by RBC

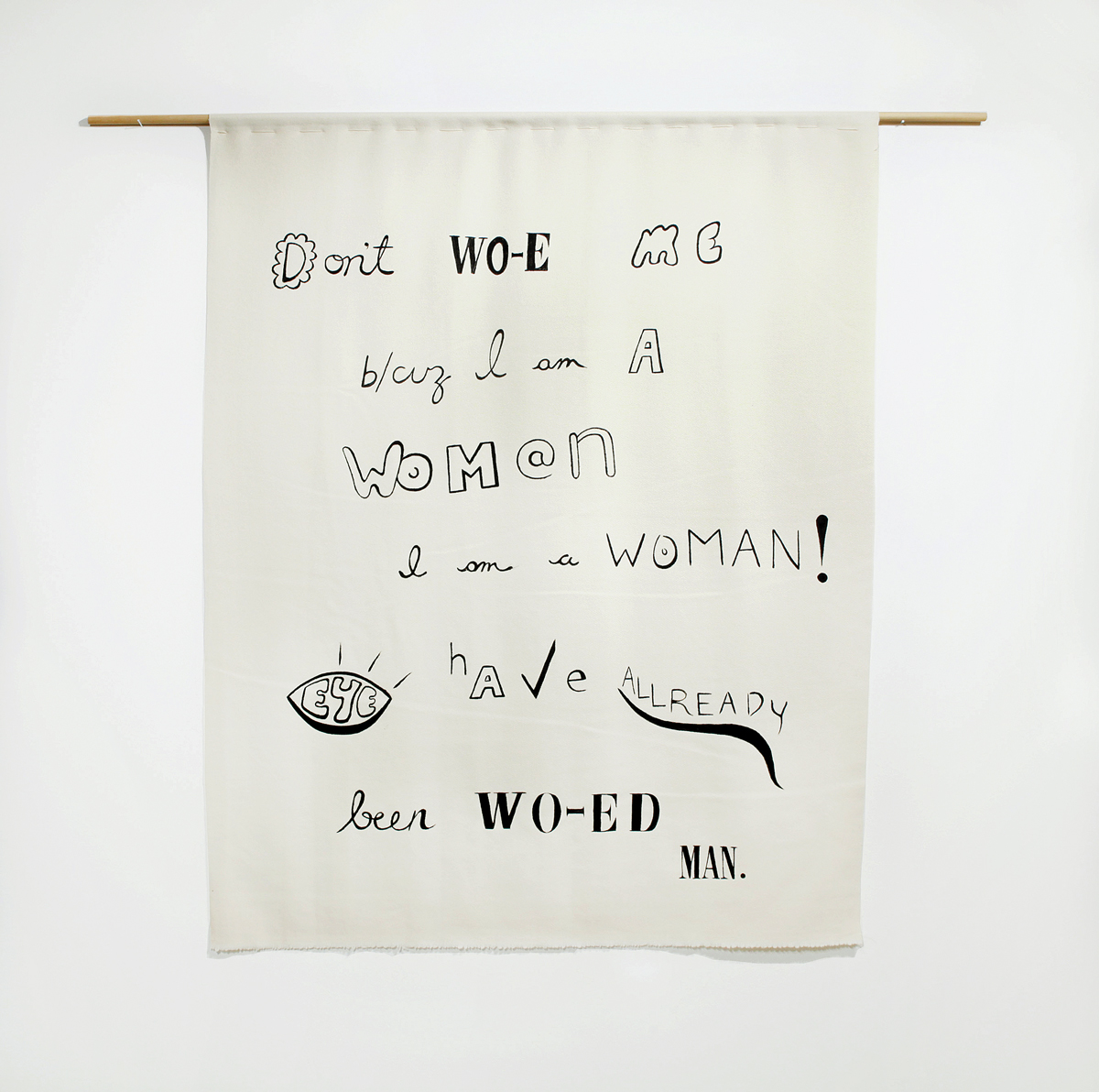

Fabiola Carranza

Fabiola Carranza’s practice is concerned with spatially reframing language. Recent projects take the form of vernacular signage in Spanish and English, presenting themselves as dry, in situ text works. But what is dry is not necessarily dried up. In a 2016 public art commission, Seven Signs, Carranza scattered mock traffic signs based on speech excerpts from vintage comic books on the Seattle waterfront. These decontextualized utterances—“AIR!,” “MUTINY!,” “ES UN IDIOMA MUY DIFÍCIL,” among others—placed otherwise unconsidered narrative cues along the routine course of a tourist path. Carranza recontextualizes language from historical sources that stem from her research approach to reading, writing and translating. “I’d say the writing happens first, or is the first step in conceiving a project,” she says, “but the equation is fluid.” Carranza’s ready-made poem, Syco-Seer, 1948 (2014), alphabetizes the 20 possible answers offered by a Magic 8-Ball. The work’s title is a nod to the 1950s fortunetelling toy’s precursor, invented by Albert C. Carter and based on a spirit-writing instrument developed by his clairvoyant mother during the Second World War. This history is distilled by Carranza into an index of opaque responses set in black-toned cyanotype. Read in verse, the non-committal tone of the 8-Ball’s stock answers exposes its dubious origin in wartime anxiety. At the same time, the work pinpoints the malleable nature of language to shape belief, suggesting, perhaps, that truth is ultimately a matter of both conviction and chance.

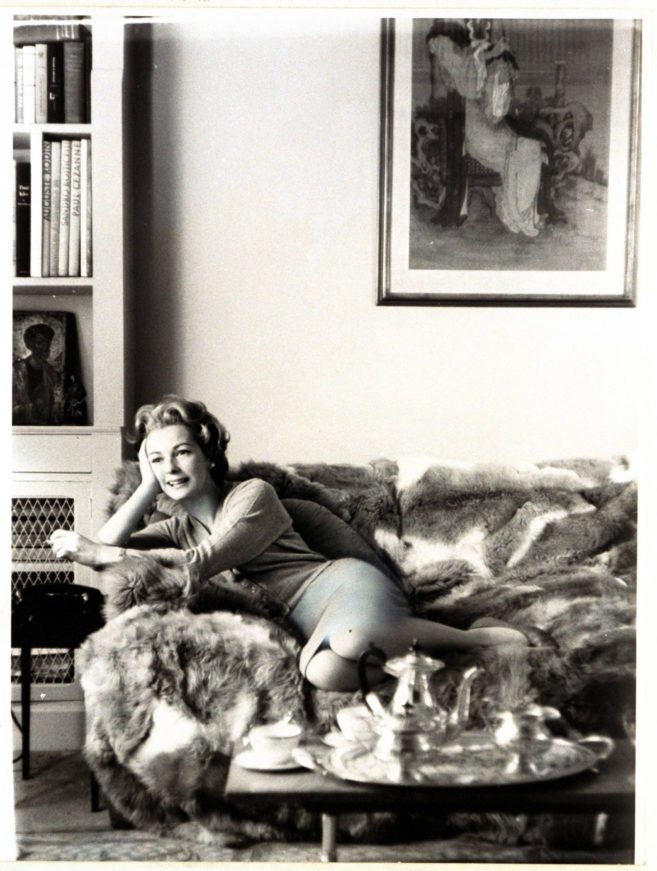

Tiziana La Melia, Page of Vapours (detail), 2012. Photocopy with unique ink on parchment covers and risograph insert by Ryan Smith, 42 pages.

Tiziana La Melia, Page of Vapours (detail), 2012. Photocopy with unique ink on parchment covers and risograph insert by Ryan Smith, 42 pages.

Tiziana La Melia

“I had been oscillating between focusing on writing or visuals, and somehow arrived at the point that I didn’t have to choose one over the other,” says Vancouver artist Tiziana La Melia

of her digressive approach. “Writing was never something I felt especially strong or good at, but it was something that felt necessary to my sanity.” It’s also an extension of her visual work, displaying different aspects of her research and thought process. La Melia’s writing blends correspondence, intimacy and incantations in an attempt to better understand desires and gripes. Nice Poem (2017) makes an indexical study of flattery, social instrumentalization and liberal feminism; she explains that “these works have been very direct and emotional, and document tiny instances of structural violence, ulterior motives, narcissism and so on.” Alongside a 2012 show at Exercise in Vancouver, La Melia inaugurated Page of Vapours, a publication whose title borrows an archaic term for feminine melancholia. “I collected writing that is produced or takes form in necessarily digressive ways. Dilating in and out of focus.” Her contributors were given two prompts: a paraphrase of W.G. Sebald, “When you release a dog into a field, it never goes in a straight line,” and a non sequitur in a dream that Freud misremembered: “I am fed morsels of cake, strawberries and spoonfuls of porridge.” Also a painter, La Melia won the 2014 RBC Canadian Painting Competition. She is now corralling contributions for Page of Vapours 2 and preparing a book of poetry with Talon Books.

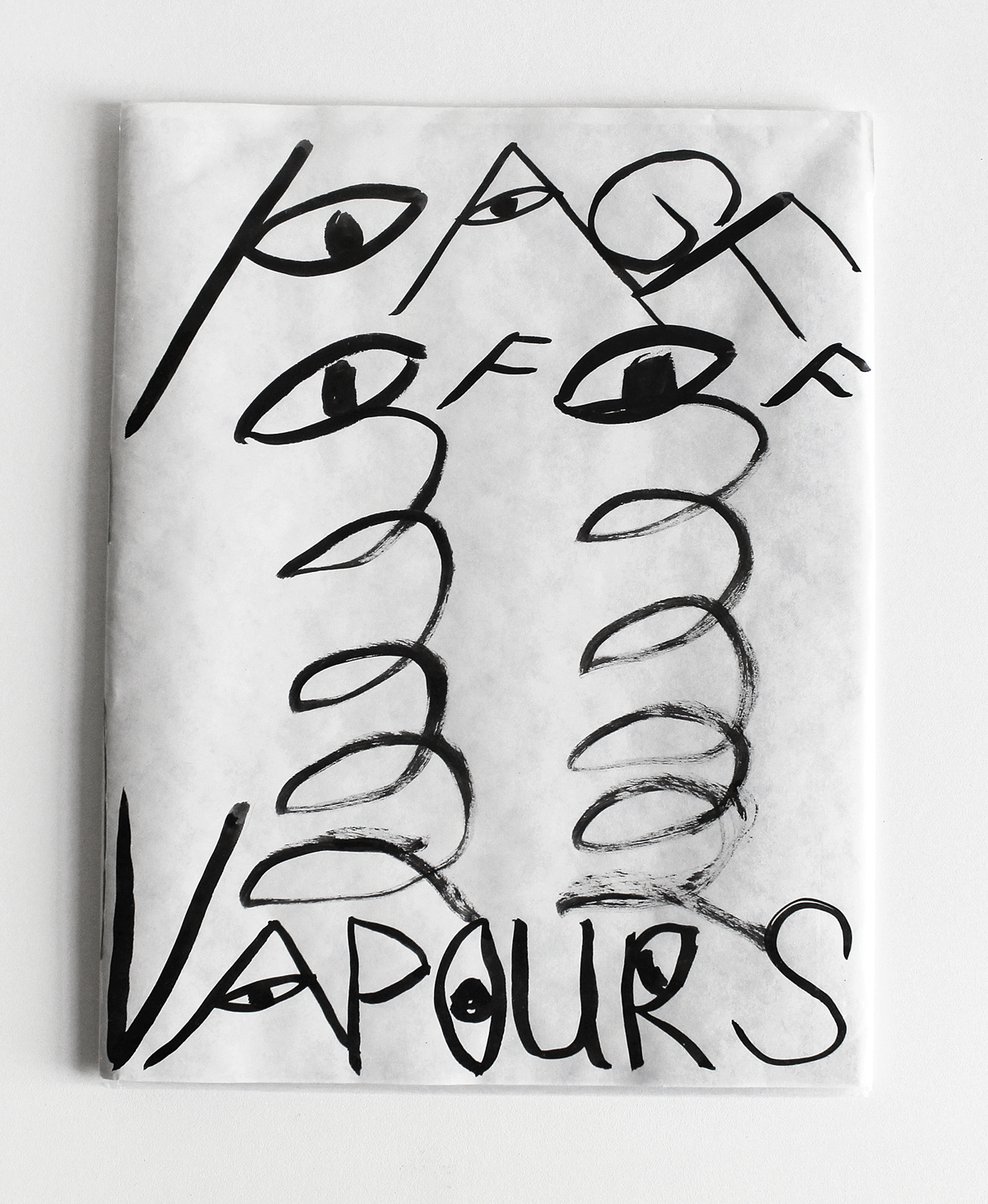

Juli Maier, Leg (detail), 2017. Comic book. Courtesy DDOOGG.

Juli Maier, Leg (detail), 2017. Comic book. Courtesy DDOOGG.

Juli Majer

Juli Majer’s comics may introduce readers to other life forms and other worlds, but she is not supplying escapism. “I’m not that interested in utopias,” says Majer. While intergalactic travel is grandiose, Majer’s nuanced narratives are interested in the pragmatic details of these other worlds. “What are the daily lives of the characters in other worlds? What gets normalized on other planets?” Her practical questions are ultimately concerned with how a social subject is formed. This curiosity compelled her to start developing an education system for the society portrayed in Leg (2017), which was published by DDOOGG, a small press she runs in Vancouver with Tylor Macmillan and Cristian Hernandez. While there are currents of speculative anthropology in her work, Majer’s narratives are also occupied with how we can meditate on personal relationships. Humans have left this planet to look at it from space in an attempt to measure and understand it; Majer says that “people are just like planets, we can study them, try to communicate with them, but we’ll never really understand what’s going on.” And, for her, the unknowability of people-as-planets can be liberating when we consider how this extends the possibility of expression. “Publishing creates personal space and allows me to get in touch with narratives that are genuine and honest to myself,” she says. “It deepens a hole, and makes a space bigger.”

Gabi Dao, Curled Up In a Spiral, 2017. CNC-milled polystyrene, resin, wood filler, micas, pigments and natural clays. Dimensions variable.

Gabi Dao, Curled Up In a Spiral, 2017. CNC-milled polystyrene, resin, wood filler, micas, pigments and natural clays. Dimensions variable.

Courtesy Artspeak. Photo: Dennis Ha.

Gabi Dao

Vancouver artist Gabi Dao writes to engage with the social context that informs her art practice. In writing about music, she assesses the contemporary conditions of its circulation, including the individuals, and identities, involved in and articulated by the music industry and media platforms. “Most music writing serves to regurgitate the experience of the music,

but it never talks directly about the underlying circumstances in which the music was produced,” she told me. In Whitney Houston, et al., a recent collection of essays on popular music edited by Casey Wei, Dao writes about M.I.A. through the lens of Trinh T. Minh-ha and Hito Steyerl. She has also written about A Fantasy in Surrey, an album composed by Ellis Sam (Same Same) entirely in the Surrey Public Library. “For me, writing was the most direct way to string together these nebulous things in order to give some visibility to Ellis and his work, which I really believe in.” As a resident at Vancouver’s Western Front, she launched a podcast series called Here Nor There. She considers it an experiment in oral publishing that encourages conversations about sound design and music between artists, writers and producers. “It was my way of saying, ‘Look, not all art lives in a gallery, not all art is made in a studio,’” explains Dao. “Why do we keep privileging these spaces?” She regularly partitions time that would ordinarily be dedicated to her sculptural practice in order to work on discursive projects, underscoring a shift in what makes an artist receptive, agile and present in their work and artistic community. “It’s not enough to just practice in my studio.”

Stacey Ho and Julia Aoki, How to Dig a Hole, 2015. Performance, 15 minutes.

Stacey Ho and Julia Aoki, How to Dig a Hole, 2015. Performance, 15 minutes.

Stacey Ho

Not long ago, Vancouver artist and writer Stacey Ho was reading about grass: “[The biology book I was reading] describes grass as early colonizers, which my brain was flipping around into an anti-colonial metaphor—grass as an ‘early remediator’ of the impact that humans have had on the land, a humble healer.” That play on grass exacting retribution for human interference in the natural world was an auspicious lead for Ho, whose recent works take the form of conversation-based performances designed to stretch the interpretive resonance of language. In Bird is Bird (2016), Ho hosted conversations in German that asked participants if they spoke bird, purple, green or stone. How to Dig a Hole (2015), a collaborative text and performative lecture with Julia Aoki, expanded the geometry of a hole to tell a story through the writing of shapes. “Fall through one story to get to another, to find another tangent that forms an invisible shape,” Ho writes. Last winter, the Capilano Review published Ho’s short story “Green House,” where her grass motif eventually found its place. The story portrays the oscillation between Marlene’s mundane daily life caring for her sick husband and her relationship with a sexually assertive but caring fugitive, Al. Ho’s writing evokes the familiar scenery of a roadside diner or a plant-laden domestic space with a cinematic precision to detail, especially in the framing of bodies. However, “Green House” is also peppered with magical realism. Ho’s imagery represents how human bodies are evenly affected by the forces of nature and supernature, and the weight of interfacing with the unfamiliar.

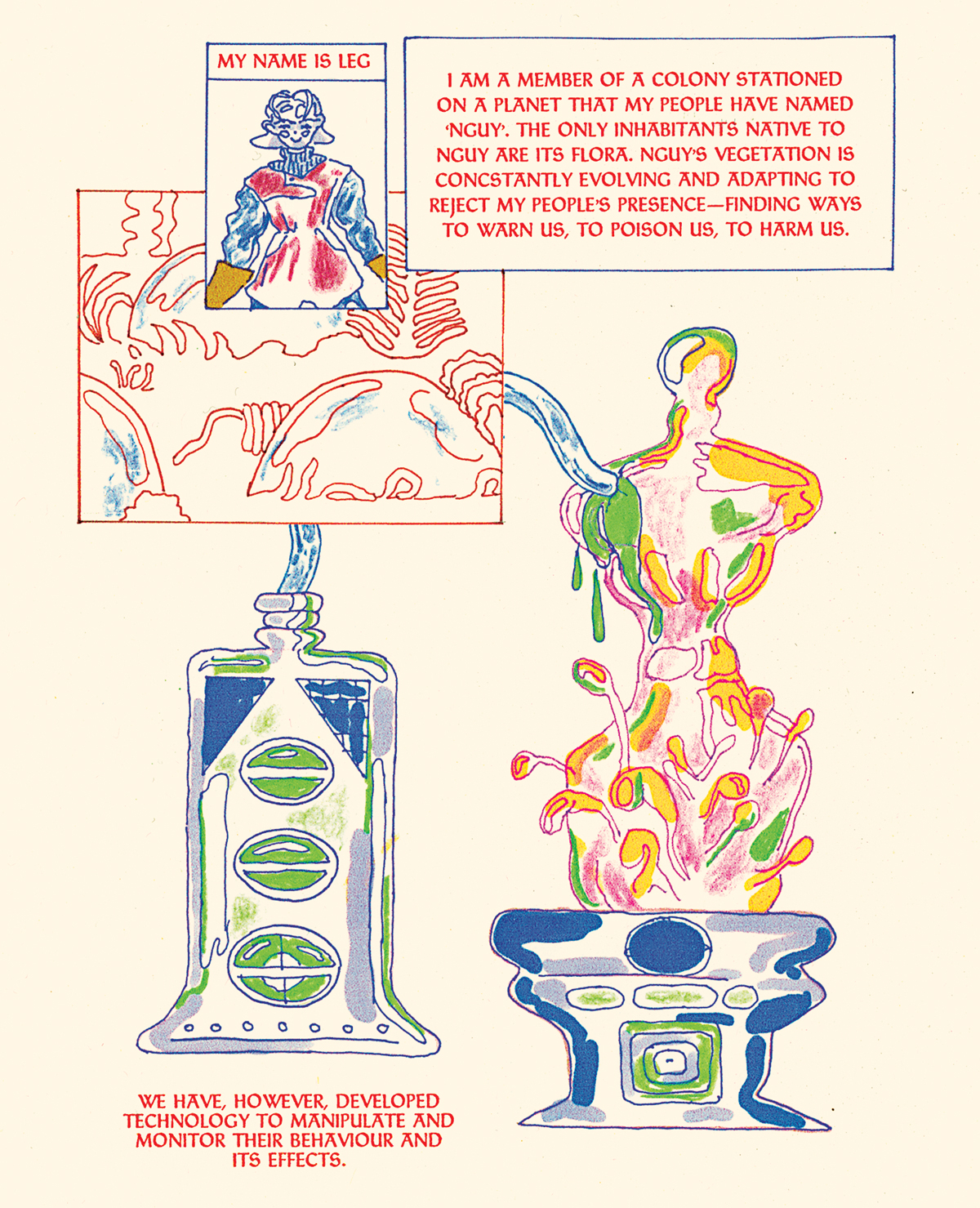

Sharona Franklin, Missing Wo[E]Mans, 2016. Wool, acrylic, wood and cotton thread, 1.49 x 1.18 m. Courtesy/Photo: Hyoin Bae.

Sharona Franklin, Missing Wo[E]Mans, 2016. Wool, acrylic, wood and cotton thread, 1.49 x 1.18 m. Courtesy/Photo: Hyoin Bae.

Sharona Franklin

Vancouver artist Sharona Franklin employs the vocabulary of bureaucracy and biotechnology to articulate the lived experience of a body shaped by these forces. “The thing about biotechnology is that it should matter to everyone,” she explains. “The idea that we’re separated from the chemical world doesn’t make sense.” Franklin’s 2016 book Rental Bod is an accumulation of cell phone photos and tablet sketches, collected images, sumi-e ink and Sharpie drawings, digital scans with iPhone notes and scans of painted text. “I work to circulate personal mythologies of biomedicine, gender, botany and rhetorical, theological and bureaucratic systems,” she says. For Franklin, the anatomies of this book can be read as analogous to a body: many parts make a whole and images can be an outer shell while the words course beneath the images to energize the visuals. It’s a strategy that strives to advance accessibility and understanding in holistic ways that folds into her life as a woman with a disability: “I would like my own ideas and writing to stand alone from the fact that I have a disability,” she says, “but also to acknowledge the influence of my own experiences within these systems, and how alienating disability can be for women.” Franklin often records her prose works for the visually impaired and hopes to have them translated into Braille.

Alexandra Bischoff, Rereading Room: The Vancouver Women’s Bookstore (1973–1996) (detail), 2016–18. Photo: Sungpil Yoon.

Alexandra Bischoff, Rereading Room: The Vancouver Women’s Bookstore (1973–1996) (detail), 2016–18. Photo: Sungpil Yoon.

Alexandra Bischoff

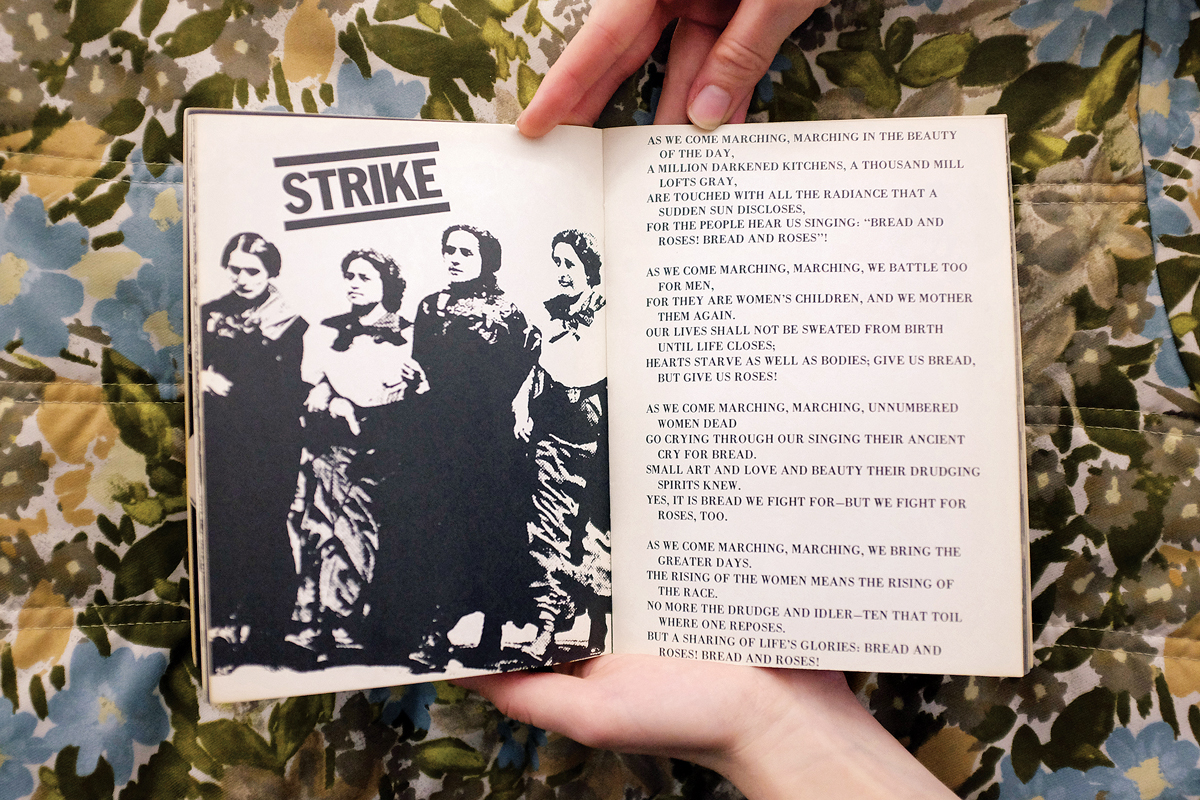

Last summer, Alexandra Bischoff unearthed the first inventory catalogue of the Vancouver Women’s Bookstore. A focal point of the city’s feminist network when it opened in 1973, the bookstore survived three break-ins, a firebombing and two relocations, then closed in 1996. For Rereading Room (2016–18), Bischoff reassembles the store’s original stock as closely as possible, creating a living history for artists and activists to occupy and reinterpret. A declaration on the last page of the project’s catalogue reads: “doing this catalog was awful, tho i got / more reading done than in last 2 years: / reading in bed on toilet at table on bus. / worked insane stretches of time, / surviving on cookies & yogurt & green / pea eggswirl soup with cockroaches in it. / didn’t sleep except occasionally, on / people’s floors, curled up in the bags / under my eyes. / my name is jeannine mitchell & i wouldn’t / dream of forgetting to scrounge whatever / credit i can off this damn thing. i promise / never to do it again.” The passage was formative for Bischoff in thinking of reading as an exercise in endurance rather than pleasure, and as text as a stage set for performance. Bischoff is currently researching the life of Joanna Hiffernan—largely known for spurning Whistler after posing for Courbet’s L’Origine du monde (1866)—for a durational performance that subverts the narrow understanding of model and muse. It’s an act of embodied recollection that reveals a deeply felt textual intimacy to research. “There is a tenderness I feel,” she says of the project. “It’s not necessarily nostalgia, but preservation for something that was formerly invisible.”

Byron Peters and Tyler Coburn, Resonator</em (detail), 2016–17. Zip file, takeaway and diagrams, dimensions variable.

Byron Peters and Tyler Coburn, Resonator</em (detail), 2016–17. Zip file, takeaway and diagrams, dimensions variable.

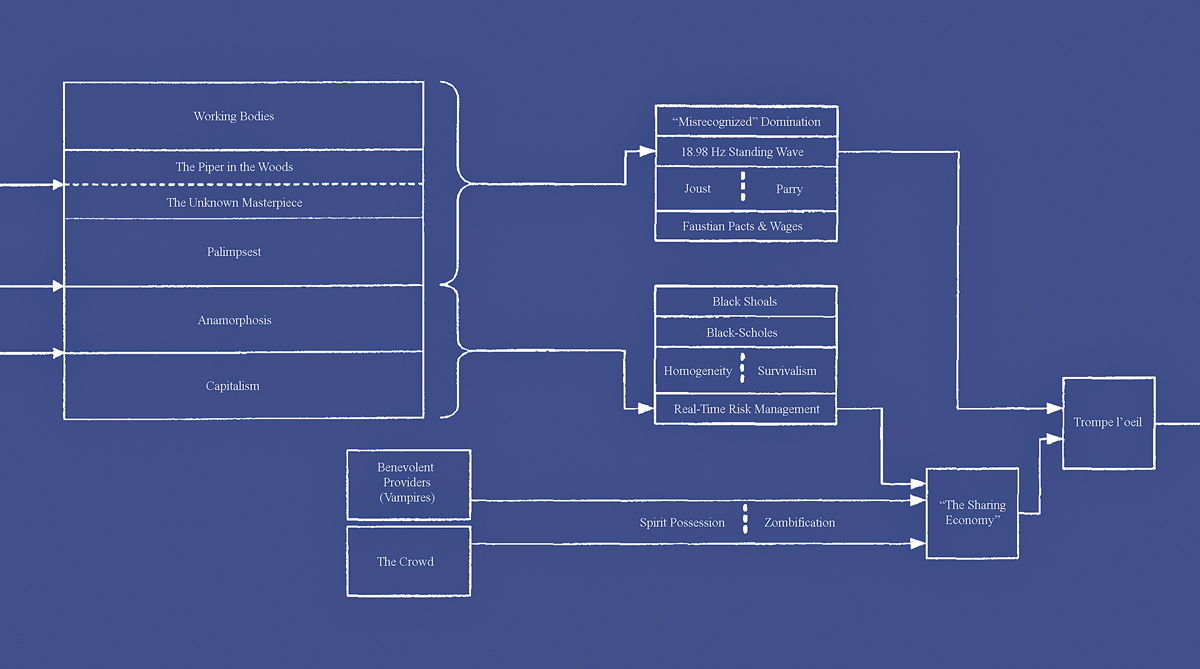

Byron Peters

Byron Peters claims to be a slow writer. Not because of his literal writing speed, but because his writing often emerges from a prolonged collaborative investigation, or “thought experiment.” “A lot of the writing projects that I’ve worked on are collaborations that sometimes unfold over years,” says Peters, who works in Vancouver. Resonator (2016–17), a multi-part project with Tyler Coburn, is based on an anecdote about Nikola Tesla nearly destroying a partially constructed building while testing his earthquake machine on Wall Street. Over a long email correspondence, Peters and Coburn generated a zip file containing related images, songs, GIFs and two texts: a poem grafted over the schematics for a highspeed trading computer and a short story. The story, which was exhibited as a stack of free posters in “The House of Dust d’Alison Knowles” at Darling Foundry in Montreal last summer, portrays a workroom in a factory producing resonant frequencies that cause workers to faint and have visions. During the exhibition, the artists’ zip file was also attached to the gallery’s newsletter, effectively spamming the museum’s listserv with their artwork. Resonator is a work that contracts and expands on many terms: decompressing years of dialogue into a zip file, unzipping an email attachment, picking up a poster at a gallery, reading a short story. It circulates as a polymorphous multiple—easily shared, and therefore, difficult to censor.

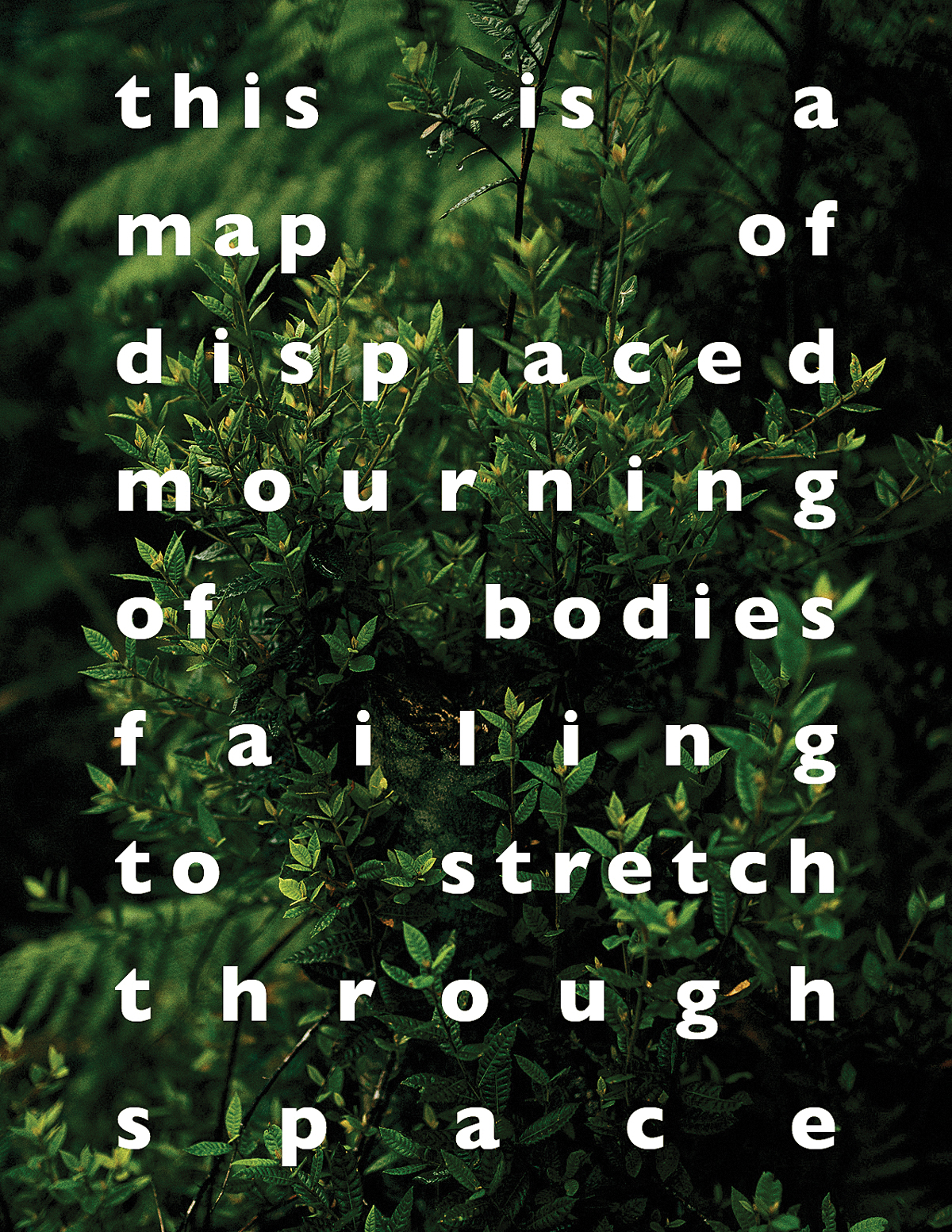

Anahita Jamali Rad, this is a map, 2017.

Anahita Jamali Rad, this is a map, 2017.

Anahita Jamali Rad

Anahita Jamali Rad wants to destroy capitalism, so why has she started a clothing line? Fear of Intimacy is a hybrid form of publishing, clothing and public art. It resurfaces a central question from her 2016 book of poetry, For Love and Autonomy: what does it mean to carve out sovereignty under late capitalism? In Fear of Intimacy, the acronyms “STFU” and “FTP” reside where a logo would normally be emblazoned on a pair of sport socks. A T-shirt reads, “you’re not my friend”—a refusal to inflate the currency of friendliness trafficked on social media. If the text bites and the statements register as bratty or indignant, it might be because you’re not privy to the alienation that sears us, the contradictions between political principles and economic survival, and the extension of solidarity in every act of expression. “It’s about making explicit that this is what capitalism, imperialism, colonialism, white supremacy, sexism, etc., make us feel, so let’s find each other and relate, feel a little bit better so we can actually do something about it,” explains Jamali Rad, who was born in Iran and now lives in Montreal. The clothing gives the wearer a way to hide their discontent in plain sight, but also gives us the ability to spot each other. “Unless you’re completely off the grid, there’s no way you’re not being commodified. And I’m not really the off-the-grid type. I kind of like being around other people,” she says. As she writes on the first page of For Love and Autonomy, “‘I’ is always necessarily a ‘we.’” Jamali Rad is as eloquent as she is tactical in her invitation to commiserate together—be it through poetry or a sweet T-shirt.

Casey Wei, AK002 hazy-x.o. Virgo Ox, 2016. Cassette tape and chapbook (with Pink Noise by Instant Coffee).

Casey Wei, AK002 hazy-x.o. Virgo Ox, 2016. Cassette tape and chapbook (with Pink Noise by Instant Coffee).

Casey Wei

Casey Wei is a Renaissance woman. She has played in the bands Late Spring and hazy, curated for the art rock? concert series, directed a music video for Destroyer as Karen Zolo, operated the Karaoke Music Video Maker Free Store, and she runs the music and printed matter label Agony Klub. But as she told me, “Everything I do comes from my writing.” Agony Klub is named after an underground casino from a Raymond Chandler novel. The “K” is an embedded reference to filmmaker Rainer Werner Fassbinder, and in its abbreviated form, AK also invokes Chris Marker’s documentary on Akira Kurosawa. This assortment of personal tastes in film and literature exposes a construction of meaning that more closely resembles an artwork than a mandate for an editor or publisher. As an artist, Wei doesn’t write to publish but to articulate how and why words pile up from organic impulses. In December 2017, she published a book of meditations on filmmaker Yasujir¯o Ozu, Ozu’s Seasons, with Blank Cheque Press, which she read from alongside a screening of Ozu’s Floating Weeds at Spare Room in Vancouver. “When I saw my first Ozu film, it took me to the idea of the ‘syntax’ of his films, that fixation on language, structure, the grammar of something,” Wei says. “I don’t think of what I do in terms of ‘texts.’ We assign narrative to everything, it’s in our nature to look for patterns.”

This post is adapted from the feature article “Text-Based,” generously supported by RBC in the Spring 2018 issue of Canadian Art. RBC is passionately committed to supporting emerging artists across Canada and internationally, and is proud to partner with Canadian Art on this Spotlight series.

Fabiola Carranza, Seven Signs (Air!), 2016. Prismatic vinyl on aluminum, 38 x 45.7 cm.

Fabiola Carranza, Seven Signs (Air!), 2016. Prismatic vinyl on aluminum, 38 x 45.7 cm.