There are many routes of approach to the polymathic oeuvre of G.B. Jones, though none are a common thoroughfare. There are the zines: J.D.s (acronym for juvenile delinquents) being foremost among many; the Super 8 films: The Troublemakers (1990), The Yo-Yo Gang (1992), The Lollipop Generation (2008); and the bands, like Fifth Column, a cornerstone of the ’90s riot grrrl movement, and my particular point of entry at the age of 15. Their titles suggest postures of juvenescent revolt, yet all are internationally acclaimed milestones in publishing, independent film and alternative rock, respectively. Furthermore, all were primary sources for what became known as Queercore: a movement against normative tendencies among gays and lesbians, favouring radical aesthetics rooted in erotics and sedition. Concurrent to it all, Jones has always been dedicated to the métier of drawing.

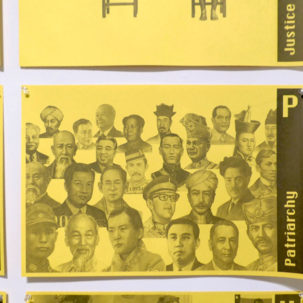

G.B. Jones, Prison Breakout #2, 1991. Graphite

on paper, 26.6 x 20.3 cm. Courtesy the artist.

G.B. Jones, Prison Breakout #2, 1991. Graphite

on paper, 26.6 x 20.3 cm. Courtesy the artist.

Beginning in 1985 Jones co-edited J.D.s, a photocopied serial publication, alongside Bruce LaBruce. Despite its ephemerality, for those in the know it had all the import of a sacred text. Like General Idea’s FILE magazine before it, and Scott Treleaven’s This is the Salivation Army after it, J.D.s was the quintessence of a strategy and tradition perhaps unique to Toronto’s underground self-publishing whereby a handful (at most) of isolated queers embellish their reality—promulgating ideologies and mythologies as if issued from a surging, numerous gang—and, in time and through force of spirit, produce self-fulfilling prophecies, attracting international attention and adding to the city’s unlikely anarchic glamour. In the course of her early editorial duties (writing polemics, collaging), divine inspiration visited Jones: Wouldn’t it be fabulous to publish all-female versions of Tom of Finland’s drawings? Those erotic vignettes, rendered in pencil with the panache of Ingres, of muscled policemen and bikers. Through a simple détournement, those drawings’ fetish for the hyper-masculine and the authoritarian could become images of liberation once again, freed from the fascist tendencies at work in gay male culture. Jones had not yet added drawing to her vocations, and, as J.D.s preferred to operate within Warholian parameters, her immediate impulse was to search for a suitable artist to whom she could outsource the job. Alas, and of course, no one could be found. So she set about the task of transcription herself.

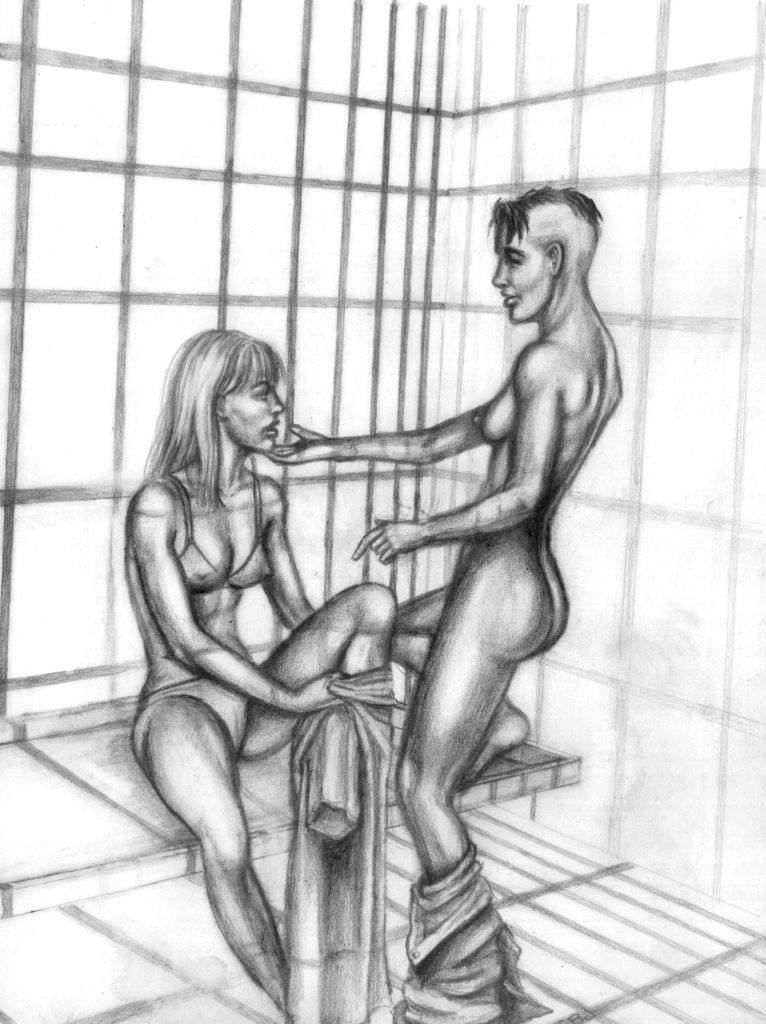

G.B. Jones, Blue Mark Morrisroe, 2004. Graphite and coloured pencil

on paper, 22.8 x 16.5 cm. Courtesy the artist/ Participant Inc., New York.

G.B. Jones, Blue Mark Morrisroe, 2004. Graphite and coloured pencil

on paper, 22.8 x 16.5 cm. Courtesy the artist/ Participant Inc., New York.

It can be said, with or without facetiousness, that Jones attended the Tom of Finland School of Drawing. Just as two bodies might find one another across a room or a bar, a communion far more formidable to the corroboration of character can occur over an expanse of time and space—by way of aligned intentions—through art. During the middle of the night, at a kitchen table under an amber bulb, pencil in hand, beside an ashtray that clocked the hours with its crumpled contents, in this quiet realm began a series Jones dubbed the Tom Girls, which was ultimately exhibited in galleries around the world and remains a pertinent contribution to third-wave feminist art. In the course of those nights Jones came into possession of a drafting skill that is at once her own, but also the latest, and possibly among the last, iterations of a descendancy in guration—cartooning in the highest sense. From the late Renaissance mannerism of Cellini, through the decadence of Beardsley and wit of Cocteau, there owed a germ of style that nally proliferated over the last century as illustration in gay magazines, of which Tom was king. Jones studied and replicated Finland’s form and technique in service of her own agenda, observing the slick of polished leather, the drapery in denim to articulate strained tumescence, the penumbra necessary to a pert nipple that is both commanding and receptive. Jones is an appropriationist by conceit. Unlike some of her contemporaries and their Pop antecedents, she appropriates not ambivalently or ironically, but with sincerity; gay culture, for better or worse, is a part of her culture, and her critique of Finland was enacted devotionally.

Classicism, a wellspring for homosexual expression up until the middle of the last century, had ballast that allowed for a complex play of innuendo; its translations into painting and literature were the mechanics and art of expressing homosexuality implicitly. A homosexual reader or viewer would nd themself deciphering its code, an intercourse arguably more asserting of difference than any explicit declarations of these desires might have been. Translation is not purely the feat of making legible that which was previously unavailable to a certain group. Its crux resides, when one considers the potential for multiple versions, in the pleasure of the reprise—a rendition motivated more by the perceived sensibilities of a text than by its actualities. The verbosity of the first English translation of Proust undertaken by C.K. Scott Moncrieff, for instance, is a corruption of the author’s more matter-of-fact French toward ameliorating its melancholic purpose: one homosexual picking up the baton lain at the feet of another, to be molded in the relay by their own circumstances and vision into an exquisite subjective. Finland flourished at the beginning of a new climate, and his images ricocheted. His men, bursting from the closet, were iconoclastic motifs picked up by punk (namely, Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren) just as by leather subcultures. The history of translation, at its most interesting, is that of hijacked content and, by reimporting nuance, Jones’s work serves this design.

Finland has only lately been metabolized by the contemporary art world, and his work remains, in popular imagination, either the stuff of the gay roué or malignant kitsch. A Norwegian artist recently recounted a different, personal story for me. At the time of his pubescence in the 1970s, Nordic progressives, in a moment of irreligious enlightenment, felt that Finland’s drawings were edifying material for youngsters whose bodies were in transformation. Issued in volumes available by Reader’s Digest–type subscription, Finland’s drawings were left (along with volumes on Will McBride) upon the low shelves of suburban Nordic dens. Certainly this isn’t the case anywhere anymore, but the anecdote is useful for contemplating the vagaries of taboo, and a scenario with which to imagine the discovery of Finland’s work by other aesthetically minded lesbian adolescents.

When the Tom Girls made their New York debut in 1991, it was concurrent with an exhibition of Finland’s drawings and sketches at the storied gallery Feature Inc., run by a man named Hudson. Finland was in the hospital and would die from emphysema later that year and Hudson was living with HIV. It is impossible to consider Jones’s early art, or any art made by homosexuals during the 1980s and ’90s, without the context of the AIDS crisis. It was a time during which Finland’s utopia was either consigned to the flames by those disgusted and panicked by its wanton, narcissistic bodies, or conversely, found to be grossly superannuated, something on the other side of the chasm of before and after, like Norman Rockwell in the wake of Hiroshima. (Finland and Rockwell are artists with much in common: propagandists in service of patriarchy in whose work the police were, however differently, worshipped.) It was a time when homosexual culture was besieged by puritanism, assimilation and AIDS, and Jones, herself a young veteran of this war, perceived its smoldering apogee on the anterior horizon, and knew instinctively that the past was where the good stuff lay.

In plainest terms, Jones’s art has always been interested in ungovernable sexualities and genders, in intimate and defiant groups of queers and women, and in the history of aesthetics forged by those who were compelled to communicate and represent their alterity through sensibilities and codes. Although they function allegorically, it’s important to note that Jones’s drawings are always revised images of those found in the media. When considered alongside her films, always starring her friends, Jones’s work is in conceptual sorority with the lesbian figurative painters Romaine Brookes and Gluck, who set against dusky hues the assertive countenances and sleeked hair of their lovers dressed in men’s clothes.

During the 15 years following the Tom Girls, Jones’s drawing spanned Caspar David Friedrich-esque landscapes, Ballardian car-crash scenes, fetishistically realistic still-lives, and portraits. These portraits are of a cast of young people—teenagers and teenage artists—all protagonists who, by turns of fate pertaining to criminalized sexuality, were ensnared in morbid and often terminal circumstances. In their faces Jones makes evident the centrifugal force of hormonal logic ring adolescent rebellion, those impulses that can devolve from caprice into lunacy in an instant as they confront societal strictures. Some portraits have a glow of hagiography— icons because they are symbols of manipulation within a world of manipulation. Each has a definite story that reminds us that it was not long ago that all homosexuality was criminal, and moreover of the duality of criminalized bodies as often being civilized bodies as well. The true ideal of Civilization is the pursuit of art and beauty in a world free from all prudery, superstition, prejudice and cruelty. One drawing, after a self-portrait by the photographer Mark Morrisroe—during his years as a hustler, and before his death from AIDS—is a picture that emits something like a tinnitus ring in the psyche of queer artists, reminding them of their everlasting obligation to both ranks.

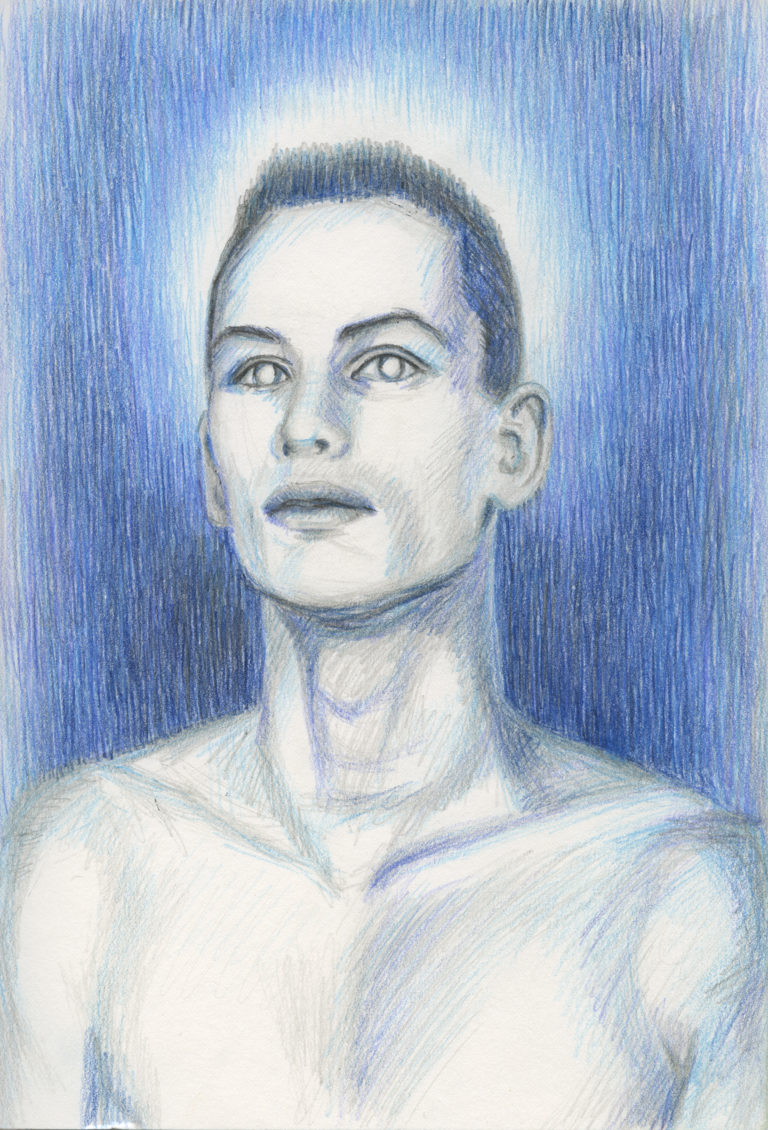

G.B. Jones, Doreen Valiente, 2017. Graphite on paper, 27.9 x 21.5 cm.

G.B. Jones, Doreen Valiente, 2017. Graphite on paper, 27.9 x 21.5 cm.

Jones’s latest series of drawings departs from Finland’s meticulous finish for an intuitive, loose and more rapidly rendered likeness. They are portraits of witches, both real personages and those from film and television. Almost all are women, and most are middle-aged. To their overlooked demographic Jones gives aspects of indomitability, from dandyish insolence to an air of consequential power. She re-imbues their well-circulated images from popular and occult culture with a sense of life. There is Agnes Moorehead as Endora from Bewitched; Joan Bennett in her final film role as Madame Blanc; Doreen Valiente, Wiccan liturgist and writer; Rosaleen Norton, an occultist, artist and leader of her own coven. Their energy and image defies the sublunary, workaday world of men, and it is interesting to consider them as Jones’s symbolic milieu.

The middle-aged protagonist in Nancy Mitford’s novel Don’t Tell Alfred (1960), unsatisfied by family life, wonders, “What was I doing on earth at all and how was I going to fill in the thirty-odd years which might lie ahead before the grave? …I had often longed to leave behind me a token of my existence, a shell on the seashore of eternity.” Though Jones’s subjects refuse existential crisis, society nevertheless perceives them as beyond their use-value, and therefore invisible; in spite of it they make invisibility their prowess. Literary theorist Leo Bersani wondered, in Homos (1995), if the visibility gays had gained through assimilation would paradoxically lead to invisibility: “The slogan ‘We are everywhere’ appears to be saying: ‘Look around and you’ll find us in all the places to which you thought you had denied us access.’ But the slogan could also have a quite different gloss: ‘Look around and you’ll never find us because we are everywhere…even if we do the most outrageous things…we will remain unlocatable.’” If, in our retrograde present, as progress welds society together to serve its ends, queers come full circle to the invisibility where the mature woman has always dwelt, then Jones’s witches posit two crucial things: the potential for all of us to become Fifth Columnists; and a reminder that feminism must always be an exigency of queer politics, just as we must understand that homophobia is an extension of misogyny.

The Canadian art world has so far allotted Jones that which is broadly accorded to those of her gender and generation; elsewhere her importance is recognized. In her manifold ways, Jones displays queer genius; like Cocteau, she has moved along her era with an aesthetic that appears prescient, but is in fact of-the-moment. From the ruins of gay liberation, over the bulkhead of late-capitalist gay commodification, beyond the cloy of nostalgia, through the condensed atmosphere of identity politics, she sees our perpetual aim: the resurgence of homosexual art, a two-pronged weapon—one fork, visual pleasure, the other, transgressive pleasure.