A nuclear accident in Chalk River. Mercury poisoning in Grassy Narrows First Nations. A funeral for the Don River in Toronto. These are just a few events that have demonstrated Canada’s troubled relationship with an increasingly un-natural, inhospitable environment.

These three events are among many highlighted in the current exhibition “It’s All Happening So Fast: A Counter-History of the Modern Canadian Environment,” a show that sharply contrasts traditionally romantic notions of a barren, unclaimed Canadian landscape or terra nullius.

On now at Montreal’s Canadian Centre for Architecture until April 9, and making its Toronto debut as part of CONTACT in May, the exhibition considers the implications of human-influenced environmental phenomena—from acid rain in Sudbury to pesticides found in the Arctic—presenting a dense almost-manifesto that dismantles spectacles of wilderness.

But can an exhibition ever truly be a manifesto? And, more pressing, can an exhibition be an effective critique of industries and cultures when its own strategies are often entangled with those same industries and cultures?

Thick with archival material from the National Film Board, Library and Archives Canada and Arkitektur-och Designcentrum Stockholm, among others, placed alongside recent artworks by Douglas Coupland—whose inclusion seems more populist than reflective—the contents of “It’s All Happening So Fast” deal a critical blow to the myth (or at best, the well-established fable) of the modern “natural” environment.

Chief among CCA director and curator Mirko Zardini’s critical moves is historicizing current conceptions of the landscape by asking: What comes after the environment? In a time of unprecedented human intervention in the landscape, it seems more apt to refer to the “natural” environment in the past tense.

But as intelligent and calculated as this history is, and as effective as it is at provoking discomfort in pairing archival evidence with the question above, it is perhaps more uncomfortable to consider the ways that the exhibition itself capitalizes on these strategies and stories of exploitation.

In the gallery “Stories of an Obsession,” for instance, Jean Chrétien, then Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development, refers to the North as “the last frontier” in archival footage from the late ’70s, casually brushing aside opposing voices from its residents.

I couldn’t help but notice a similar sense of curatorial conquest in recent architectural exhibitions that mine the Canadian landscape, its complex history, and those who inhabit it—including rural communities in the North— for academic and cultural resources. Recent Canadian entries to the Venice Architecture Biennale such as “Arctic Adaptations” in 2014, “Extraction” in 2016, and even “It’s All Happening So Fast,” inevitably partake in this strategy, whether accidentally or intentionally.

John Denniston, Improvised oil-spill cleanup at Stanley Park, Vancouver, 1973. Courtesy Canadian Centre for Architecture.

John Denniston, Improvised oil-spill cleanup at Stanley Park, Vancouver, 1973. Courtesy Canadian Centre for Architecture.

Indeed, in the midst of Canada 150, and the institutional funding it has brought, it seems that these histories of destruction are being extracted from the landscape and commodified in the same way as oil and natural gas. In the economic landscape of late capitalism, perhaps all resources—natural and historic—are destined to become commodities.

It’s telling that, inside the exhibition, the nation is still referred to as an “object” of study. And, a full-page ad for the exhibition’s publication appears on the back of the first page of the newspaper The Reminder—itself the sort-of-catalogue, guide and “official dispatches from the exhibition.” Both these choices underline the exhibition’s seemingly contradictory move to commodify notions of nation, knowledge and history.

Douglas Coupland’s wry slogan “Thinking About the Future Means You Want Something” seems apt. Part of the series Slogans For the Early Twenty-First Century (2011–16), which either begins or concludes the exhibition, depending on one’s route, Coupland’s words provoke a question in this context: Aren’t all manifestos—the politically driven Leap Manifesto and the Suzuki Foundation’s Carbon Manifesto/mock-trial—in the end, products for consumption?

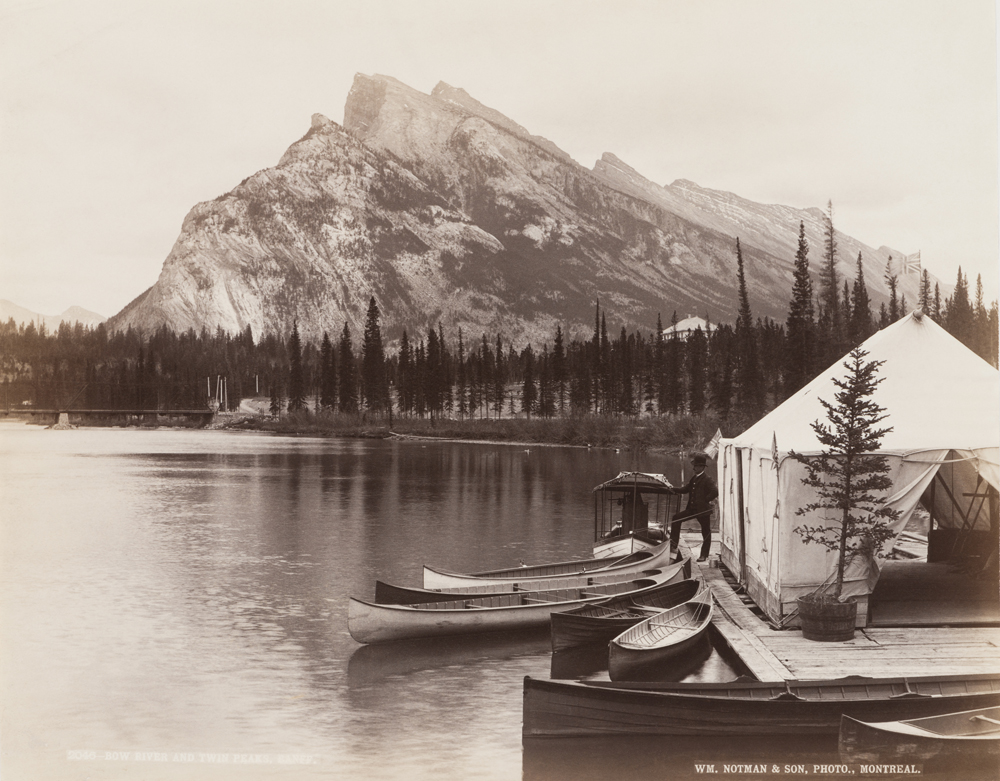

William Notman and Son, Bow River and Twin Peaks, Banff (Alberta), 1889. Courtesy Canadian Centre for Architecture.

William Notman and Son, Bow River and Twin Peaks, Banff (Alberta), 1889. Courtesy Canadian Centre for Architecture.

There are other concerns in “It’s All Happening So Fast” regarding our relationship with technology—concerns that ultimately imply architecture. Scientific mapping and advanced instrumentation have aided in reducing the natural environment to a standing reserve of resources waiting to be extracted or “stripped of all value except an economic one,” as Zardini writes.

Yet, the exhibition often falls into the habit of using these kinds of instrumentalizing representations to reflect the slow violence and ecological damage it intends to chastise. Large-scale maps and infographics occupy several walls of the exhibition, attempting to communicate the extent of resource extraction, but employ the same techniques of representation that have enabled nations to divide, colonize and exercise control over territory— forms of control we still negotiate today.

In wanting to establish new narratives of the modern landscape, the contents of “It’s All Happening so Fast” are often contradictory. While critiquing some of the calculated views of expansive wilderness used to promote the forestry and tourism industries—similar to William Notman’s scenic Banff tableau that opens the show—the exhibition also includes recent proposals that turn large-scale communal “ecological” or “closed loop” camping into a touristic and academic commodity.

“It’s All Happening So Fast: A Counter-History of the Modern Canadian Environment” (installation view at the Canadian Centre for Architecture), 2016. Courtesy Canadian Centre for Architecture.

“It’s All Happening So Fast: A Counter-History of the Modern Canadian Environment” (installation view at the Canadian Centre for Architecture), 2016. Courtesy Canadian Centre for Architecture.

There is a craving for a kind of radical agency woven into the skilful alt-historical narrative of disturbing truths in “It’s All Happening So Fast.” One senses a desire to elicit a call to arms, to inspire change, to help us rethink the fabricated divides between natural and artificial—a desire for the exhibition itself to become a kind of pseudo-manifesto for potential habitation after the myth of natural environment dissolves completely.

But the pessimism emanating from the exhibition’s content is difficult to escape, and it, too, seems to contradict the more manifesto-like, utopia-tantalizing impulses. This pessimism seeps everywhere, like the blood pooling at the base of Coupland’s Ice Machine (2014).

Though quietly venerating historical utopian proposals such as the BGHJ Architect’s PEI Ark and Ralph Erksine’s Ecological Arctic Town—an uncanny parallel to “Arctic Adaptations” utopian visions of the Nu(new)-north— “It’s All Happening So Fast” also expresses suspicion and concern with one of Coupland’s less than optimistic Slogans, namely, “The Past Is Useless.”

Ultimately, as much as it tries, “It’s All Happening So Fast” can’t seem to find the right words to form a succinct ending. Confronting these dark ecologies and ongoing environmental violence is a lofty task for any exhibition, and hence resists a tidy conclusion.

The exhibition, instead, leaves us surrounded by well-meaning environmental manifestos, (from the aforementioned Leap to Carbon) and interventions like Cornelia Hahn Oberlander’s landscape for the Northwest Territories Legislative Assembly Building—projects that offer only a brief, cursory insight into the massive, complex project of stitching together fragile ecosystems, let alone explore the depths of the amassed archival testimonies from Indigenous groups speaking out against the continued violence against the land.

A snapshot from a walk around the Northwest Territories Legislative Assembly Building, Yellowknife, with landscape architecture by Cornelia Hahn Oberlander, 1991–94. Courtesy Canadian Centre for Architecture.

A snapshot from a walk around the Northwest Territories Legislative Assembly Building, Yellowknife, with landscape architecture by Cornelia Hahn Oberlander, 1991–94. Courtesy Canadian Centre for Architecture.

Interestingly, the exhibition catalogue, edited by Zardini and CCA curator of public programs Lev Bratishenko, offers more tangible insights for moving forward compared to the exhibition. A transcribed conversation with environmental lawyer David R. Boyd and general counsel to the Haida Nation Terri-Lynn Williams-Davidson illuminates environmental legislation, treaty negotiations and landmark cases addressing complex entanglements between land, resources and post-human ethics through Indigenous knowledge—discussions especially relevant in the wake of protests in Muskrat Falls and Standing Rock.

In light of the Whangui River in New Zealand gaining similar legal rights as a human being, one of Williams-Davidson’s statements resonates: life after the environment, she argues, “would require a change in worldview and a reconsideration of our history, which has been one of taking and denial.”

Thomas Coon’s testimony in the NFB’s 1991 documentary Our Land Is Our Life, highlighted in the exhibition, also comes close to a rallying cry. “Our land is our life…our land is our future,” he declares in protest to the James Bay Project. (The irony here is that Hydro Quebec funds and is often noted as a proud partner of CCA exhibitions.)

But this future involves finding a way to live alongside non-humans, sentient and non-sentient, friendly and volatile, and to ultimately insist upon the exhibition’s governing question: Who is the environment for?

This future also requires finding other historical approaches, ones that curtail the capitalist traps that got us here—in particular the notion that the environment and its resources exist as a commodity for us, whether physically, aesthetically, economically, politically or even curatorially.

Though the CCA, as prime custodian of architectural history at home and abroad, has an obligation to expose these marginalized counter-histories, the institution is also faced with negotiating the more weighty ethical questions of what histories can be told, and by whom.

In asking whom the Canadian landscape is for, we must also ask: Who is this history really for?

Amid all the inevitable paradoxes of “It’s All Happening So Fast,” Zardini’s best-laid plan is to help us confront the nature we are not, together—in all of its complexities and contradictions.

Evan Pavka is the editorial intern at Canadian Art. He has a background in design and architectural history.

Postcard showing the Superstack in Sudbury, Ontario, from the University of Waterloo Library’s Special Collections and Archives, Canadian Coalition on Acid Rain fonds.

Postcard showing the Superstack in Sudbury, Ontario, from the University of Waterloo Library’s Special Collections and Archives, Canadian Coalition on Acid Rain fonds.