The march of time invariably warps an artist’s life and career, and there is no greater example of this than Vincent van Gogh. In the 122 years since his death, he has been the avatar for a whole host of artistic stereotypes: the neglected artist-hero who toiled himself to ruin; the manic genius; the man unhinged by his own artistic temperament; the sensitive aesthete battered by the cruelties of his surroundings. And for each stereotype, there is a concomitant school of art-historical interpretation. The most colourful one I’ve heard, in the context of a college art history class, was that his signature brushwork was an expression of his tinnitus (which also served to explain that unfortunate episode with his ear).

There are shades of truth to all of these personae, but the facts of his life are well-known, and are far less romantic than the Kirk Douglas distortions: a man prone to anxiety and depression; a man who ensconced himself in the centre of the Parisian art scene of the mid 1880s; a man whose career was largely mishandled by his art-dealer brother; a man possessed of an exceptionally probing artistic intellect whose preoccupations form a bridge between impressionism and modernism.

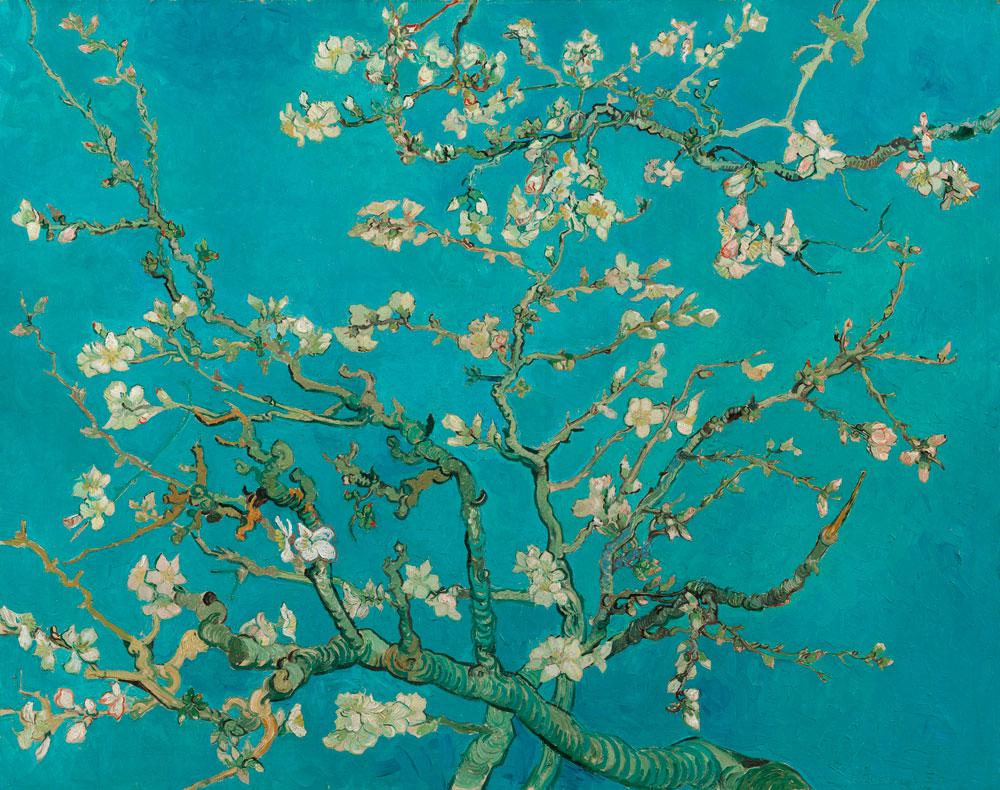

It’s a relief and a delight, then, that “Van Gogh Up Close,” an expansive show of his later work on currently at the National Gallery of Canada, is sober and restrained. Curators Cornelia Homburg and Anabelle Kienle Poňka dismiss any tragic-romantic leanings, and maintain a firm focus on the work; biography is only alluded to in the form of dates and locations, and didactic material is geared exclusively towards formal discussions of the paintings. It’s possibly the most academic blockbuster show I’ve seen, and while it’s certainly not a new way of seeing Van Gogh, it is the best way.“Van Gogh Up Close” begins with his move to Paris in 1886; the entire exhibit spans a four-year period (he died in 1890), and it’s an astonishing four years for Van Gogh: a restless, searching journey in which he absorbs, distills and discards influences as he attempts to deconstruct painting. His earlier work done in Belgium and the Netherlands is absent here, so the seismic shift brought on by his painterly absorption of the French avant-garde is without context; he was always a talented painter, but that translation marks his emergence as a rigorous painter. Some influences are fleeting, springboards to other painterly investigations, like his wrestling with Manet and Degas. Others—such as the precise fluidity and formal augustness of Japanese prints—make indelible marks that carve out his career path.For all the security of his place in the pantheon of early modern art history, Van Gogh does not sit easily in any one school or category. He shares his sense of colour, exercised via plein-air painting, with the impressionists; his formal and compositional rigour aligns him with the avant-garde Salon painters; his deconstructive painterly approach allies him with Cézanne and the Fauves. But abstraction was never a goal; form and composition were simply a foundation for what he wanted to achieve; and he was never purely concerned with optics. What Van Gogh was obsessive about was a felt reality.“Up Close” proceeds more or less chronologically, and thus, one can see the artist develop the painterly vocabulary we all know him for: the thick hatch marks, lines, scribbles and dots that stride across the picture plane. And vocabulary is, quite literally, what Van Gogh was after. With each stroke and swipe and daub, he wanted to create a complete painterly language that didn’t just describe an observed vista; he wanted a syntax, a grammar, a conjugation that could describe a phenomenon. How to portray not only what a blade of grass looks like, but how it feels—its texture, its springiness? How to translate, within the same painting, the movement of wind currents through the air and through a field of wheat? How to speak of the light of the French countryside, to iterate simultaneously its colour, its glare and its warmth? It’s most plain in his drawings, which are, unfortunately, absent here: how precise he is, without the benefit of colour, in the material flatness of ink, to describe in lines, dots, dashes and smudges these perceptual phenomena.This bedrock of Van Gogh’s painterly investigation is what is elided in any biographically romantic view of his work, and what is happily foregrounded in Homburg and Poňka’s curation. Gone is the Kirk Douglas Van Gogh, blurting out his anxious vision onto a mute canvas. In fact, as is readily in evidence in his letters (some of which are included here), Van Gogh was anxious to be rid of his emotional turbulence, because it impeded his productivity. When we look at “Van Gogh Up Close,” we see a focused, meticulous painter who was confronted with an aesthetic language in the midst of radical change—who wanted to master it, and speak it for a new century.