As Peter von Tiesenhausen tours me through “Elevations,” his solo exhibition at the Art Gallery of Grande Prairie, it is difficult to gauge whether he is more invested in the work on view here or in the new Demmitt Community Centre, an hour’s drive away. The internationally acclaimed environmental artist and activist talks about each—the art that symbolizes a spiritual journey, and the community centre that he has been instrumental in creating—with equal pride, passion, humour and angst. His conversation reveals how his art practice affected the way the community centre was conceived, and vice versa. Some of the images and materials in his mixed-media show, which functions as a mid-life meditation on creative aspiration and the making of meaning, are directly connected to the realization of the building.

Recently completed in the rural hamlet of Demmitt, Alberta—von Tiesenhausen’s home turf, roughly 80 kilometres northwest of Grande Prairie—the community centre represents four years of his volunteer labour. Together with his wife Teresa, he was responsible for finding public and private funding for the smartly conceived, handsomely executed structure. Working alongside friends, neighbours and tradespeople, he also contributed some 1,000 hours of hands-on physical labour to its construction.

More importantly, the community centre signifies von Tiesenhausen’s desire to rally participants around the idea of employing sustainable building practices and sourcing local, renewable or reclaimed materials. From the straw-bale walls to the pine-beetle-kill timbers and the composting toilets, the building evinces the artist’s longstanding environmental concerns—concerns he previously expressed through his sculptures, paintings, large-scale earthworks and site-specific installations. Despite some initial local resistance to the project (fear of change, he suspects), the place has become a hub of social and cultural activity—it has hosted everything from plays and concerts to weddings, square dances and pizza parties.

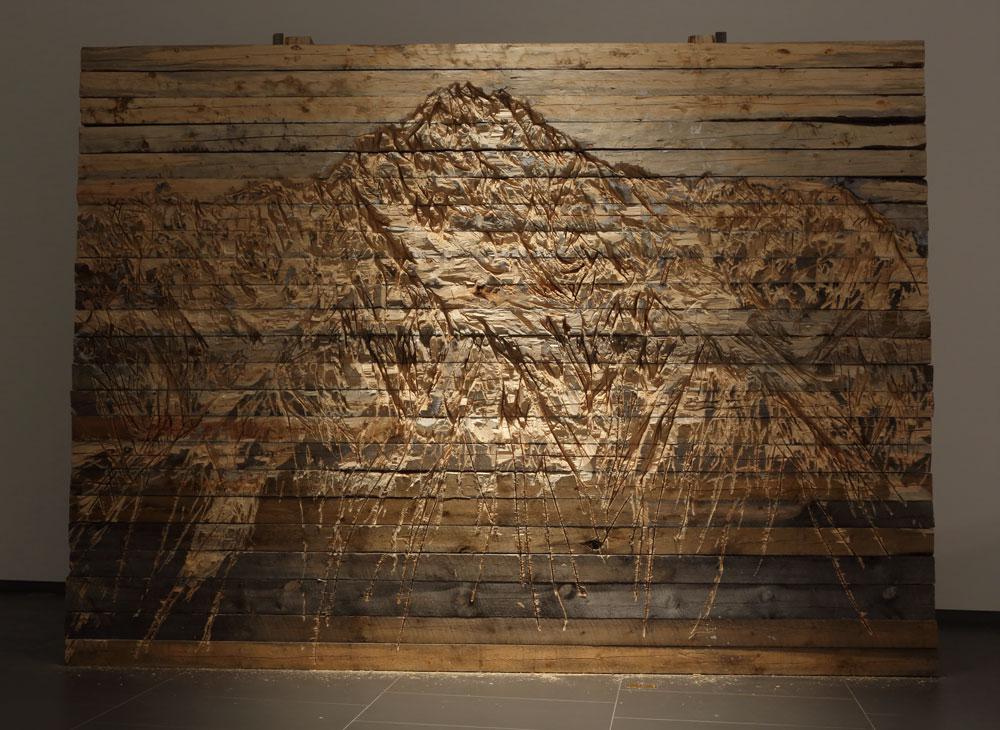

Relief (2012), one of the most monumental works in von Tiesenhausen’s show at the splendid, rebuilt-in-2009 Art Gallery of Grande Prairie consists of a flat, billboard-like stack of square-cut timbers, buttressed from behind with the same kind of mortise and tenon construction employed in the Demmitt community hall. The timbers, revealing the telltale blue stains of pine-beetle kill, are leftovers from the Demmitt project; the image gouged into them with axe and chainsaw, however, is of Mount McKinley, North America’s highest mountain peak. This work communicates a deeply romantic vision, not only in its allusions to the capital-R historic period of art and literature during which towering mountains were an essential element of the sublime, but also in its symbolism of personal aspiration, spiritual transcendence and identification with the natural world. (I’m not the first critic to analogize von Tiesenhausen’s practice to European Romanticism: John Bentley Mays has written eloquently on the subject. Still, on this visit, I am struck anew by his practice’s alignment with its poetic and spiritual goals.)

In the fall of 2011, burnt out from the exhausting and sometimes fractious community centre project, von Tiesenhausen took up a residency at the Banff Centre. He was also, he says, facing a crisis in his own artmaking: he had set his practice aside for so long while involved full-time in the community initiative that he was uncertain about how to find his way back into it. Unsure even if he wanted to. The residency, much of it spent meditating, writing, drawing, reading and talking with fellow artists, served its purpose. It renewed his belief in and understanding of his vocation, and it allowed him to reinvest himself in a way of working based on intuition rather than theory.

The Banff residency also reinforced the importance of place to his artmaking and his connection to the natural environment. These dynamics are evident in Transcendere (2011), a short video focused on von Tiesenhausen’s reclining profile, from eyebrow to neck, as he meditates, blinks and breathes slowly in and out. Eventually, his image fades into a shot of a mountaintop with a similar profile. This work conflates the artist’s creative and spiritual identification with the landscape with his amusement at noticing that the craggy peaks visible through the high windows of his Banff studio resembled his own face in profile. It’s a nifty gender reversal of the art-historical cliché that analogizes women’s bodies to the landscape. Transcendere also addresses, as Relief does, the idea of creative and spiritual retreat, of the artist seeking inspiration and enlightenment within the solitude and grandeur of wild nature.

In an untitled 2012 work, assembled in the gallery, the artist is portrayed as a kind of suffering Everyman. His figure is traced in round, brownish-black stain marks—evocative of puncture wounds or bullet holes—on warped and splintered slabs of wood. The materials von Tiesenhausen deploys here again speak to place and process: the wood was also left over from building the community centre and the rusty dots were created by setting small metal disks (waste from the fabrication of ladders that run up the sides of oil-storage tanks) on the boards, with the materials then exposed to the elements for many months.

The petroleum industry, of course, casts a long shadow across the region. One of von Tiesenhausen’s legal strategies for resisting the industry’s incursions involved making a claim of copyright to the land on which he has installed a number of his environmental sculptures. It’s the land he grew up on, the land that used to belong to his parents, the land on which he and his family live and work.

Older pieces in the show mark von Tiesenhausen’s journey to this point in his life and career. They include Bell (1996), an immense percussive instrument carved out of wood, covered in propolis (a reddish, resinous substance bees collect from tree buds and use to cement cracks in their hives) and hanging from a heavy metal logging chain. The piece is powerful, declarative and intended to be interactive—and not always simply in the obvious invitation to ring it. As von Tiesenhausen suddenly and alarmingly demonstrates, it can be ridden (at least under his watch) like a bucking rodeo animal—yee-haw! This metaphor is humorously enhanced by the two large, round clappers that dangle, like bull testicles, below the bell’s oval-shaped opening.

Amusingly, sexual imagery also plays over Music of the Spheres/Confluence (2012), a small sonic and kinetic sculpture. Its metal rockers create rhythmic rork-rork-rork sounds and cast bars of shadow back and forth across a steel plate a cut through with a vulvic slit.

One of von Tiesenhausen’s signature works is Watchers (1997), five nearly identical, sentinel-like male figures, each eight feet tall, roughly carved in wood and then burned to a charred black. Originally exhibited on a rooftop in Calgary, they inspired a beyond-ambitious, five-year, 27,000-kilometre journey around Canada. The artist stood them in the back of his old blue pickup truck, from which they could silently survey the vast and various landscapes of this country. They witnessed the wild and the cultivated, the pristine and the grotesquely damaged as von Tiesenhausen drove them in stages from exhibition to exhibition and from coast to coast to coast. Their grand tour, which included being transported by Coast Guard icebreaker through the Northwest Passage, is represented here by Odyssey, a 66-minute video compiled in 2012. Its ever-changing scenes play as a mesmerizing travelogue across a grid of moving images on a wall-mounted monitor.

Now draped with snow, the original Watchers still stand in the back of von Tiesenhausen’s truck, which is parked during the run of the show on a small plaza near the gallery’s glassed entrance hall. Their phoenix-like creation is also commemorated in Revelation (2000), an immense, wall-filling work composed of multiple charred-plywood panels, collectively carved with the image of the five figures. They are gathered around one of von Tiesenhausen’s characteristic wooden boats and are surrounded by flames that rise up against the darkness of a rural Alberta night. It’s a commanding work, evoking both creation and destruction: the figures can be read as being consumed by the flames or birthed out of them.

After we view his Grande Prairie show, von Tiesenhausen drives me, through blowing snow and a startling amount of traffic, to Demmitt. En route, he talks again about the community centre, and its inception and construction, in terms that suggest it is, itself, a work of art—part relational aesthetics (he met Nicolas Bourriaud during his Banff residency), part community-based cultural initiative, and part environmental-action plan. Not that he conceived it that way: he wanted to involve his community in the creation of an innovative and responsible model to replace an old, crumbling, mouse-ridden building—a building everyone had lost interest in.

At the new hall, he and his wife treat me to a concert by the award-winning young Winnipeg singer/songwriter Del Barber. Afterwards, we walk across the sprung dance floor, its boards salvaged from an old school gymnasium, and von Tiesenhausen recounts memories of hugely popular community square dances that took place when he was a kid. He especially remembers the neighbour who called the dances and energized the participants with his booming voice, his charisma and the skill he brought to his particular art form. “He inspired me to follow my muse,” von Tiesenhausen says now, with wonder and gratitude. In life as in art, this place tells us, the past is inextricably linked to the present, and the present to the wide blue horizon of the future.