At a time when both Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples in Canada are trying to make sense of how to meaningfully enact (re)conciliation, “Morning Star,” curated by Jason Baerg and Darryn Doull, generously offers up much-needed space for reflection and guidance.

Every year, the Jackman Humanities Institute (JHI), in partnership with the Art Museum at the University of Toronto, solicits proposals from curatorial studies students for the development of an exhibition that speaks to the research theme for the JHI that year. In response to the theme Indelible Violence: Shame, Reconciliation and the Work of Apology, Baerg and Doull’s “Morning Star” was selected as this year’s exhibition proposal, and it presents several newly created works at the institute alongside other works recontextualized for the exhibition.

Baerg, a Cree Métis artist, educator and independent curator, and Doull, a grad student in the master of visual and curatorial studies program at U of T, were thoughtful in their selection of works for “Morning Star.” The exhibition is intergenerational and inter-tribal, and it navigates diverse landscapes, both real and imagined, in an effort to foreground the importance of kinship, survivance, traditional Indigenous knowledge and place-making within contemporary Indigenous art practice.

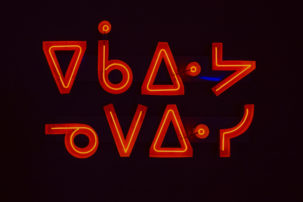

A view of Joi T. Arcand’s neon ᑭᔮᑦ (kiyām) (2017) at the Jackman Humanities Institute. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

A view of Joi T. Arcand’s neon ᑭᔮᑦ (kiyām) (2017) at the Jackman Humanities Institute. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

However, “Morning Star” isn’t the first time these two have worked together. Baerg and Doull first met several years ago while working on a collaborative project for the Judith & Norman Alix Art Gallery in Sarnia. Talking with the two of them about “Morning Star” reveals a symbiotic and collaborative relationship; they play off each other in a casual and thoughtful way.

Baerg and Doull jointly express that the exhibition is a conversation and osmosis of sorts, not only between them, but also between the JHI research fellows, for whom they hope “Morning Star” will serve as a quotidian grounding for research, guiding towards a deeper understanding of what (re)conciliation can and should mean when violence, erasure, shame and apology are truly acknowledged.

Baerg and Doull anchor “Morning Star” in anamnesis, defined as the recollection or remembrance of the past. However, anamnesis isn’t a nostalgic concept; it is active. Baerg and Doull position anamnesis as an action or gesture of looking back into the past to orient the present, but with the future in mind.

In “Morning Star,” anamnesis is activated to become an act of survivance that generates Indigenous futurities. Indigenous futurisms are more than simply imaginations of the future time; they are active articulations of the future in the present through a relinking of past with present, and the reconfiguration and reorientation of hope and action towards positive and prosperous Indigenous futures.

An installation view of “Morning Star” at the Jackman Humanities Institute with (at left) Joi T. Arcand’s neon ᐁᑳᐃᔹ ᓀᐯᐃᓸ (ēkāwiya nēpēwisi) (2017) and (at right) Adrian Stimson’s photo and text work Calling My Spirit Back (2017). All works courtesy of the artists. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

An installation view of “Morning Star” at the Jackman Humanities Institute with (at left) Joi T. Arcand’s neon ᐁᑳᐃᔹ ᓀᐯᐃᓸ (ēkāwiya nēpēwisi) (2017) and (at right) Adrian Stimson’s photo and text work Calling My Spirit Back (2017). All works courtesy of the artists. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

In spite of the architectural and epistemological challenges of inhabiting the tenth floor of the Jackman Humanities Institute, Baerg and Doull succeed in creating a humble and fertile space for engaging in meaningful dialogue.

Joi T. Arcand’s Cree syllabic neon sign, ᐁᑳᐃᔹ ᓀᐯᐃᓸ (ēkāwiya nēpēwisi, which translates to “don’t be shy”), starts the temporal occupation, visually and conceptually commanding attention, overcoming the intense architectural elements of the space. As Baerg notes, “Joi’s work holds true to where we are at [so many of us in our generation] interested in reclaiming important aspects of our identity and culture.”

For Baerg, it was essential that Alex Janvier be in the exhibition: “He was number one on my list when it came to engaging with ‘Morning Star’; his 1993 masterpiece with this title, which boldly adorns the atrium ceiling of the Canadian Museum of History, continues to powerfully radiate inspiration today. ‘Morning Star’ is an aesthetic and conceptual space in contemporary art that Janvier has occupied for decades.”

Extending their acknowledgement of senior Indigenous artists who have contributed to contemporary art practice in immeasurable ways, Baerg and Doull made the conscious decision to include Métis artist Garry Todd in the exhibition. Working in collaboration with Garry Todd’s daughter, scholar Zoe Todd, Baerg and Doull shine much needed light on an artist who has been in the background, painting for decades, but who has never received significant attention.

In fact, the presentation of Soap Berry in “Morning Star” marks the first time Garry Todd’s work is being shown in Ontario. With Soap Berry, Todd reimagines Edward S. Curtis photographs as large-scale paintings in colour, effectively Indigenizing and (re)claiming this form of visual inscription by injecting life back into the portraits. The inclusion of Todd in “Morning Star” enacts a healing journey through an acknowledgement shared between Todd, his daughter, Baerg, Doull and the viewer.

Three photographs by Nadya Kwandibens in “Morning Star” at the Jackman Humanities Institute (from left): Tee Lyn Copenace (2010), Leanne Betasamosake Simpson (2016) and Jarret Leaman (2012). All works courtesy of the artist. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Three photographs by Nadya Kwandibens in “Morning Star” at the Jackman Humanities Institute (from left): Tee Lyn Copenace (2010), Leanne Betasamosake Simpson (2016) and Jarret Leaman (2012). All works courtesy of the artist. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

In a similar way, Nadya Kwandibens vibrantly captures the beauty and complexity of Indigenous urbanity. Five photographs from Kwandibens were curated into “Morning Star”; all are part of the series Concrete Indians, which Kwandibens began as a response to stereotypical images of Indigenous peoples.

Originally producing these as black and white photographs, Kwandibens sought to contest historical uses of this aesthetic medium (most evident in the images of Edward S. Curtis) to combat one-dimensional, simplistic portrayals of Indigenous peoples. After nine years of producing this series in black and white, Kwandibens converted the series to colour to inject vibrancy back into the images to boldly and unapologetically state, “We are still here!”

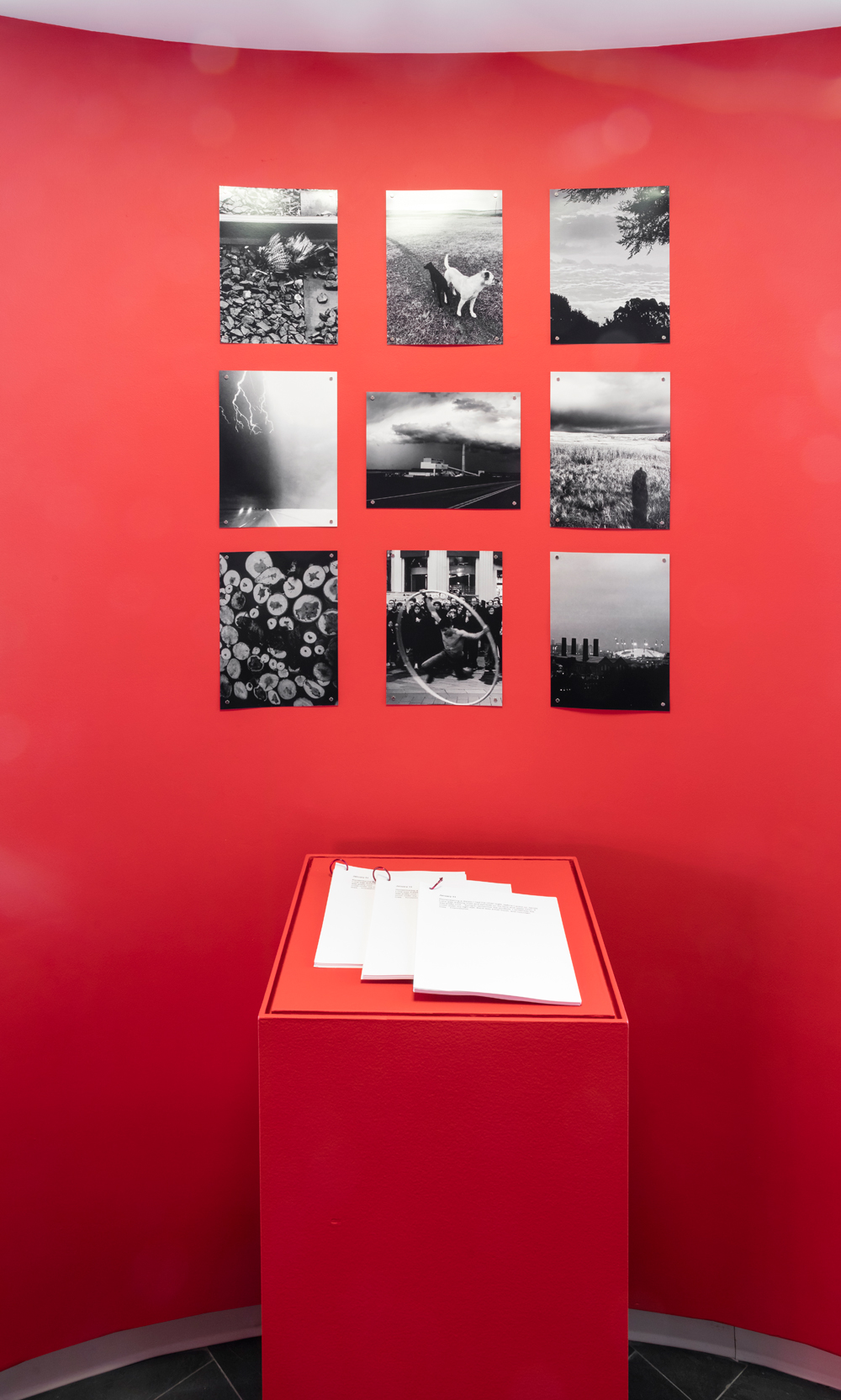

Adrian Stimson, Calling My Spirit Back, 2017. Nine black and white digital prints, inkjet text on paper, dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Adrian Stimson, Calling My Spirit Back, 2017. Nine black and white digital prints, inkjet text on paper, dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Adrian Stimson’s work Calling My Spirit Back, a new work created specifically for “Morning Star,” was born out of conversations between Stimson and Doull. A two-part work consisting of photographs taken by Stimson during a residency in Australia and two journals which detail his dreams, Calling My Spirit Back collapses past, present and future within the dreamscape.

Vulnerable, multi-temporal and interstitial, Calling My Spirit Back prophetically blends the real and the imagined, as Doull notes, to “imagine the future through the past and present, and in relation to the theme of the JHI research [on indelible violence] this year.”

Like Stimson, Bracken Hanuse Corlett’s animated experimental short film, Ghost Food, embodies a temporal shifting, situating the film’s protagonists within a dystopic future where they must look back at and draw upon their ancestral teachings in order to survive. Parable-like, Corlett’s film serves as a poignant reminder that the preservation of traditional Indigenous knowledge, which respects and honours Mother Earth, is for our benefit and the benefit of future generations.

As a Métis curator who situates survivance and relationality at the core of my practice, it is exciting to see other Indigenous curators and allies equally enacting these two ways of doing in their own practices. “Morning Star”’s compass points true, celebrating Indigenous agency and the kinship networks that support individual and collective growth and healing within the Indigenous arts community.

“Morning Star” is visually arresting, intimate and deeply thought-provoking. It is an exhibition that, with the dawn of each new day, keeps on giving.

Rhéanne Chartrand is curator of Indigenous art at the McMaster Museum of Art in Hamilton.