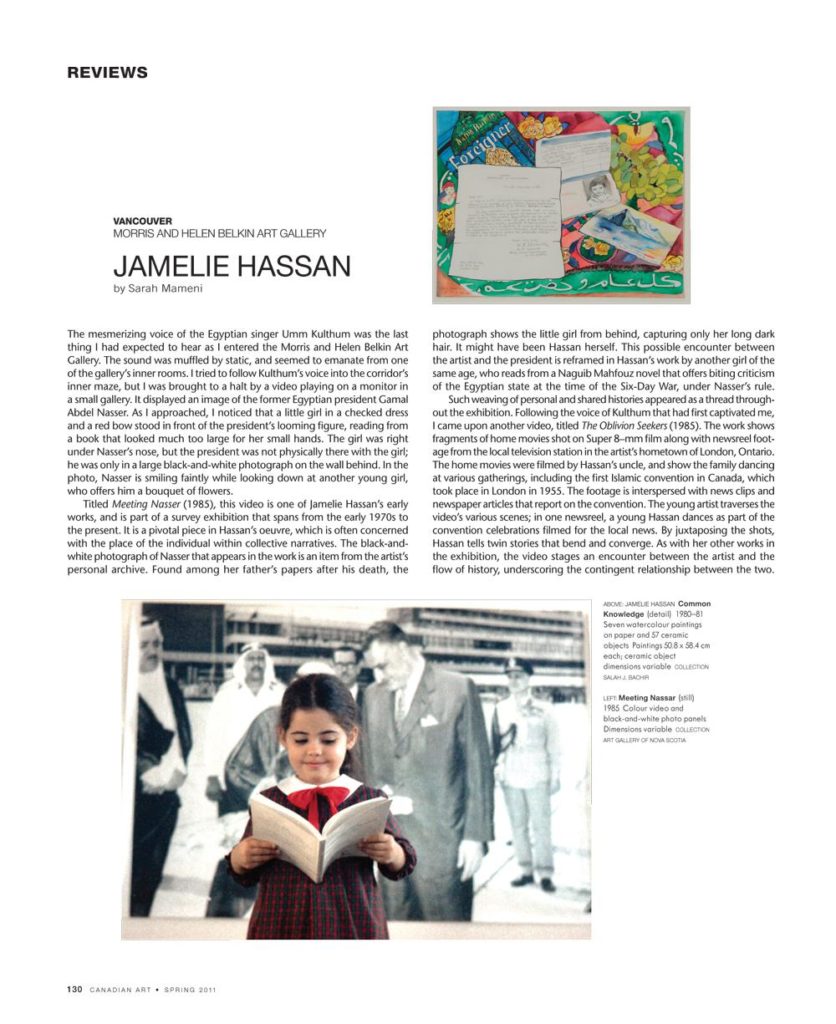

The mesmerizing voice of the Egyptian singer Umm Kulthum was the last thing I had expected to hear as I entered the Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery. The sound was muffled by static, and seemed to emanate from one of the gallery’s inner rooms. I tried to follow Kulthum’s voice into the corridor’s inner maze, but I was brought to a halt by a video playing on a monitor in a small gallery. It displayed an image of the former Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser. As I approached, I noticed that a little girl in a checked dress and a red bow stood in front of the president’s looming figure, reading from a book that looked much too large for her small hands. The girl was right under Nasser’s nose, but the president was not physically there with the girl; he was only in a large black-and-white photograph on the wall behind. In the photo, Nasser is smiling faintly while looking down at another young girl, who offers him a bouquet of flowers.

Titled Meeting Nasser (1985), this video is one of Jamelie Hassan’s early works, and is part of a survey exhibition that spans from the early 1970s to the present. It is a pivotal piece in Hassan’s oeuvre, which is often concerned with the place of the individual within collective narratives. The black-and- white photograph of Nasser that appears in the work is an item from the artist’s personal archive. Found among her father’s papers after his death, the photograph shows the little girl from behind, capturing only her long dark hair. It might have been Hassan herself. This possible encounter between the artist and the president is reframed in Hassan’s work by another girl of the same age, who reads from a Naguib Mahfouz novel that offers biting criticism of the Egyptian state at the time of the Six-Day War, under Nasser’s rule.

Such weaving of personal and shared histories appeared as a thread through- out the exhibition. Following the voice of Kulthum that had first captivated me, I came upon another video, titled The Oblivion Seekers (1985). The work shows fragments of home movies shot on Super 8–mm film along with newsreel foot- age from the local television station in the artist’s hometown of London, Ontario. The home movies were filmed by Hassan’s uncle, and show the family dancing at various gatherings, including the first Islamic convention in Canada, which took place in London in 1955. The footage is interspersed with news clips and newspaper articles that report on the convention. The young artist traverses the video’s various scenes; in one newsreel, a young Hassan dances as part of the convention celebrations filmed for the local news. By juxtaposing the shots, Hassan tells twin stories that bend and converge. As with her other works in the exhibition, the video stages an encounter between the artist and the flow of history, underscoring the contingent relationship between the two.

This is an article from the Spring 2011 issue of Canadian Art. To read more from this issue, please visit its table of contents.

Spread from the Spring 2011 issue of Canadian Art

Spread from the Spring 2011 issue of Canadian Art