In her exhibition “Indian Candy,” Dana Claxton sifts and reclaims indigenous histories and epistemologies, working with media appropriated from Internet sources and photographs she took at Writing-on-Stone Provincial Park/Áísínai’pi National Historic Site, an ancient petroglyph and pictograph site in southern Alberta. The glossy, brightly coloured surfaces of many of the works highlight the expressive manipulation of photography as a medium, creating tension between the seductive power of colour, the problematics of history and the presence of indigenous peoples throughout it.

Claxton’s exhibition engages hidden histories of indigenous peoples, specifically the legacy of Sitting Bull, of whom Claxton is a descendant. The candy-like surfaces of many of the works are trickster shifts in themselves; the media archive of indigenous icons has been polished, coloured and transformed into another being altogether. A warrant letter to arrest Sitting Bull, juxtaposed with Buffalo Bill letterhead and the signature of Colonel Cody, is printed in a punchy red in Wild Red Envelope (2013). It recalls the numerous indigenous leaders who performed in Wild West shows and, at the same time, the violent seizures of territory and people as well as the failed agreements between indigenous nations and settler states. In the light-jet print Geronimo in Pink (2013), she presents the name Geronimo, a hero for indigenous peoples and a reminder of what Ojibwe scholar Gerald Vizenor deems “survivance,” a portmanteau of survival and resistance. Based on an actual drawing by Sitting Bull, Sitting Bull Draws the Dandy (2013) portrays a colourful, top-hatted figure that sets a lighthearted tone.

The work is not all sweetness however. There is a sobering narrative with her image Love Me (2013), created in reference to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, imploring people not to just think of indigenous peoples as souvenir dolls at tourist stands but rather as equal citizens. Another work, Blue Headdress (2013), plays with perception: the closer one comes to the image, the more pixelated and bead-like the surface becomes, conveying the oscillating power of colour and art within indigenous performance to overturn colonial expectations. As a reminder of the spiritual nexus throughout Claxton’s practice, the photographs of the ancient petroglyph and pictograph site in coatings of purple and blue highlight the transcendent power of art.

Collectively, these archival juxtapositions and bright, reworked icons and symbols might be read as an implicit critique on the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s current efforts to provide solutions for generations of trauma and cultural fracture that indigenous peoples face, although Claxton’s high-gloss works avoid an overtly critical edge. “Indian Candy” re-centres our relationship to colonial and indigenous histories. It draws us in to take another look at the sweet, sick, tasty and troubled layers of culture consumption.

This is an article from the Spring 2014 issue of Canadian Art. To read more from this issue, visit its table of contents. To read the entire issue, pick up a copy on newsstands or the App Store until June 14.

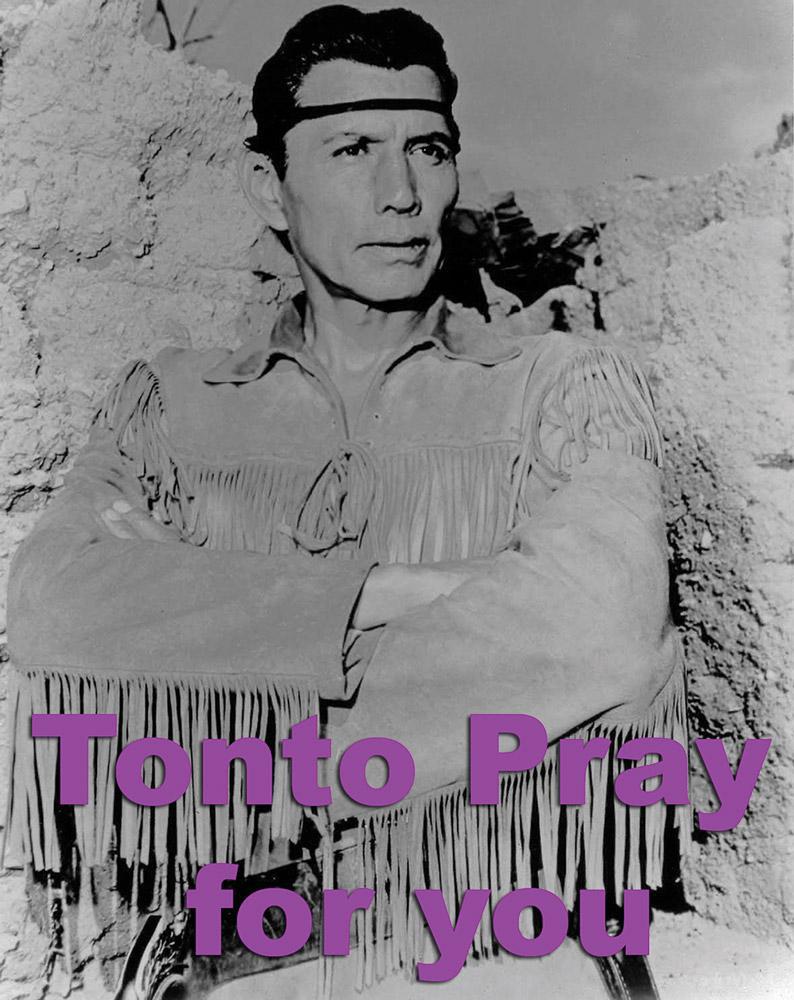

Dana Claxton, Tonto Prayer, 2013. Aluminum-mounted light-jet print, 22.3 x 17.7 cm.

Dana Claxton, Tonto Prayer, 2013. Aluminum-mounted light-jet print, 22.3 x 17.7 cm.