Chris Cran is one of Canada’s most celebrated painters, but he’s rarely written about as just that. The cult of the Calgary-based artist’s personality precedes him. Many reviews of Cran exhibitions reveal that he is down-to-earth, charming, very funny and prefers to wear all black. Known as a godfather of the Calgary art scene, he’s a board member at Stride Gallery, a teacher at the Alberta College of Art and Design and a mentor and magnanimous supporter of up-and-coming artists in his hometown. To six kids, he’s also Dad. Before his National Gallery of Canada survey exhibition, “Sincerely Yours,” which is on view in Ottawa until September 5, Cran was there in spring 2015 to put together “It’s My Vault,” a showcase of works by 15 artists he admires and is influenced by—a wonder wall of sorts. He included one of his own works in that selection, which makes sense, because he has long been one of his own favourite subjects.

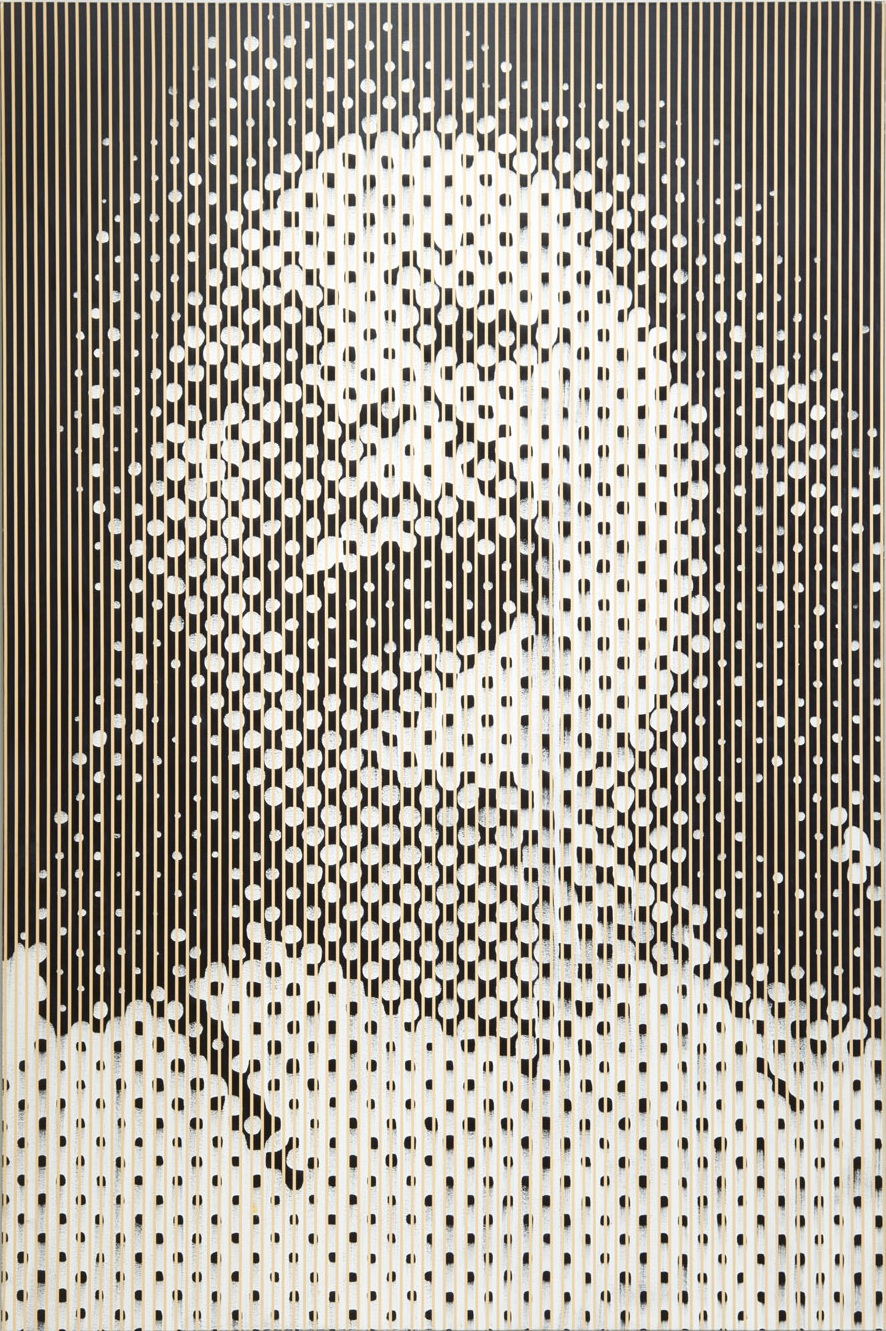

Chris Cran, My Face in Your Home, 1986. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa Photo © NGC. Organized by the National Gallery of Canada and the Art Gallery of Alberta as part of the NGC@AGA exhibition series, with the generous collaboration of the Southern Alberta Art Gallery.

Chris Cran, My Face in Your Home, 1986. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa Photo © NGC. Organized by the National Gallery of Canada and the Art Gallery of Alberta as part of the NGC@AGA exhibition series, with the generous collaboration of the Southern Alberta Art Gallery.

The person responsible for this Cran fandom is Cran himself, of course. In 1984, he began painting The Self-Portrait Series, whose central character is the artist, bedecked in a brown or blue suit and trilby, often playing the self-satisfied salesman. Like a photo-bomber, the main character of the series—Cran’s surrogate, his puppet—wanders in and out of massive realist paintings that depict shop-worn jokes, idioms, tropes and fantasies in flawless oil renderings. There’s a man literally shooting himself in the foot; a wife admonishing a husband (both roles played by Cran) for coming home late; and even a group of gun-toting naked women in wartime Vietnam up to their waists in water, while Cran, in suit and trilby, impotently holding a plywood rifle, enters from stage right. It’s all utterly ridiculous, and it’s meant to be, without equivocation.

Chris Cran, Self-Portrait Accepting a Cheque for the Commission of This Painting, 1988. University of Lethbridge Art Collection. Gift of Peter D. Boyd, 1995. Photo M.N. Hutchinson. Organized by the National Gallery of Canada and the Art Gallery of Alberta as part of the NGC@AGA exhibition series, with the generous collaboration of the Southern Alberta Art Gallery.

Chris Cran, Self-Portrait Accepting a Cheque for the Commission of This Painting, 1988. University of Lethbridge Art Collection. Gift of Peter D. Boyd, 1995. Photo M.N. Hutchinson. Organized by the National Gallery of Canada and the Art Gallery of Alberta as part of the NGC@AGA exhibition series, with the generous collaboration of the Southern Alberta Art Gallery.

The first work he produced in this series was Self-Portrait with Large Audience Trying to Remember What Carmelita Pope Looks Like (1984). Cran remembers being a kid in Salmon Arm, British Columbia, watching television, when a woman came onscreen and introduced herself, saying, “Hi, I’m Carmelita Pope.” Cran, then 10 years old, remembers thinking, “Why does she think I’m supposed to know who she is?” In the painting, he sits in a chair trying to recall this trivial childhood memory, while a large, crudely sketched audience eagerly waits for the fuzzy picture of a woman beginning to form above his head to sharpen into focus. The real joke here is that the woman depicted isn’t Carmelita Pope at all; Cran ripped the image out of an advertisement for a Magic Art Reproducer in one of his old pulp magazines, where he sources much of his material from.

Chris Cran, Large Orange Laughing Woman, 1991. Collection of Wade Felesky and Rebecca Morley. Photo M.N. Hutchinson. Organized by the National Gallery of Canada and the Art Gallery of Alberta as part of the NGC@AGA exhibition series, with the generous collaboration of the Southern Alberta Art Gallery.

Chris Cran, Large Orange Laughing Woman, 1991. Collection of Wade Felesky and Rebecca Morley. Photo M.N. Hutchinson. Organized by the National Gallery of Canada and the Art Gallery of Alberta as part of the NGC@AGA exhibition series, with the generous collaboration of the Southern Alberta Art Gallery.

In other works from this series of self-portraits, we see beginnings of techniques that show up in series to follow. After The Self-Portrait Series, Cran moved away from photo-realism and experimented with Op art, Pop art and abstraction. He likes experimenting, keeping things fresh, but what remains near constant is his Kodachrome palette, suitable for someone whose aesthetic sensibilities were moulded by an early love of 1950s toy and product packaging. In Self-Portrait – Temptation of a Saint (1986), the Cran character temporarily loses his sense of self as he becomes transfixed by an image projected by his cathode-ray television set: a tarantula has crawled onto James Bond’s pillow, and Cran’s crept to the edge of his seat, gripping the armrests. On the surface of the glowing-blue television screen, which is painted with lighter brushstrokes, there are faint traces of horizontal scan lines, the kind that used to appear on television and computer monitors when you tried to capture their screens on another screen.

Chris Cran, Red Man Black/Cartoon, 1990. Collection of the artist. Photo M.N. Hutchinson. Organized by the National Gallery of Canada and the Art Gallery of Alberta as part of the NGC@AGA exhibition series, with the generous collaboration of the Southern Alberta Art Gallery.

Chris Cran, Red Man Black/Cartoon, 1990. Collection of the artist. Photo M.N. Hutchinson. Organized by the National Gallery of Canada and the Art Gallery of Alberta as part of the NGC@AGA exhibition series, with the generous collaboration of the Southern Alberta Art Gallery.

We naturally know how to look past such visual obstructions and isolate the images contained behind the lines. Cran’s Stripe Paintings (1989–) and Halftone Paintings (1990–93) play with this human propensity to find and make meaning. He distorts still lifes, portraits and landscapes by adding screens of stripes (also nodding to Modernist painting conventions) or by enlarging images until they nearly dissolve into abstraction entirely, becoming collections of dots that only coalesce into discernible shapes when you squint or step backwards. Nowadays, of course, you get the same effect when you view the paintings through a smartphone, whose screen does the work for you—or takes the fun out of it, depending on how you look at such things. These distortions are cheeky misdirections that hold the viewer captive for a little bit longer than they ordinarily might linger in front of a painting. “It’s a cheap trick,” Cran tells interviewer William Wood in the exhibition’s award-winning catalogue, “but it works.”

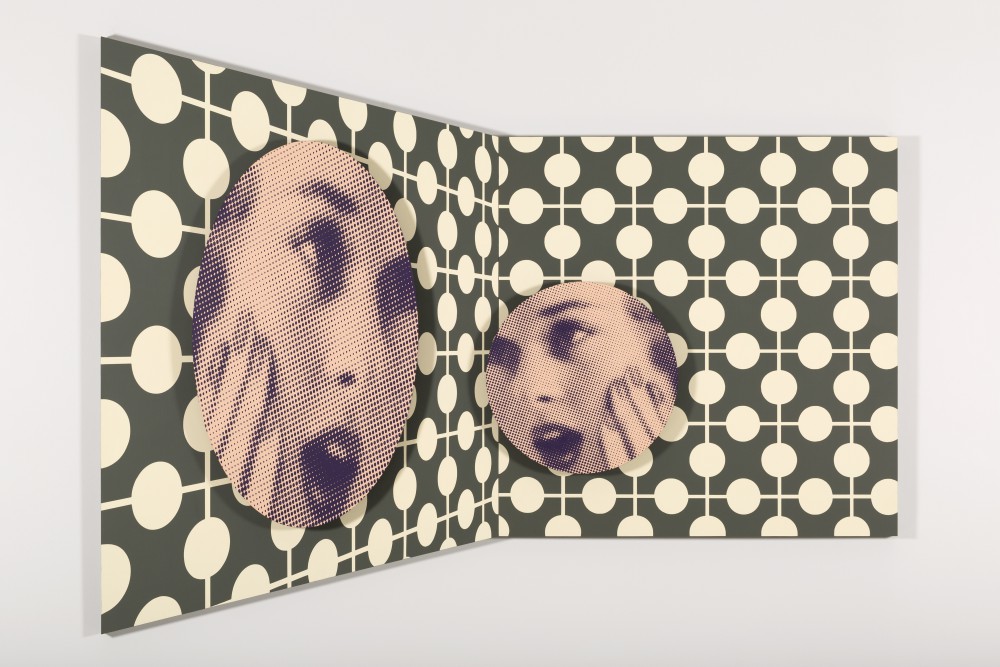

Chris Cran, Mirror, 2014. Courtesy of the artist and Wilding Cran Gallery, Los Angeles. Photo David Miller and Petra Malá Miller. Organized by the National Gallery of Canada and the Art Gallery of Alberta as part of the NGC@AGA exhibition series, with the generous collaboration of the Southern Alberta Art Gallery.

Chris Cran, Mirror, 2014. Courtesy of the artist and Wilding Cran Gallery, Los Angeles. Photo David Miller and Petra Malá Miller. Organized by the National Gallery of Canada and the Art Gallery of Alberta as part of the NGC@AGA exhibition series, with the generous collaboration of the Southern Alberta Art Gallery.

Audience engagement is paramount to Cran. We see it in his Abstract Paintings series (1995–2009), where he creates optical illusions that reward the viewer who takes time to move around and consider the picture plane from various angles, and notably in his Chorus series (2012–15), which positions tondi of blown-up, close-cropped faces, ripped from 1950s and ’60s ads, displaying ranges of emotion, around works from other series, such as Framing Device Paintings (1996–2001). Just as the Cran character in The Self-Portrait Series is a stand-in for the artist, the anonymous faces that make up Chorus—how quick we are to try to see if we can recognize any of the faces, to ascribe meaning to them—are stand-ins for the audience, like the chorus in Ancient Greek theatre. They smirk, gasp, look apprehensive, quietly observe, or ooh and aah like rock ’n’ roll groupies, creating different dialogues depending on how they are arranged and around what other works. They set the tone. As anyone who’s bad at telling jokes knows, it’s not what you say that counts, but how you deliver it. At the end of the National Gallery’s exhibition, there are works from Chorus installed in the staircase, surrounding you, in effect making you the artwork.

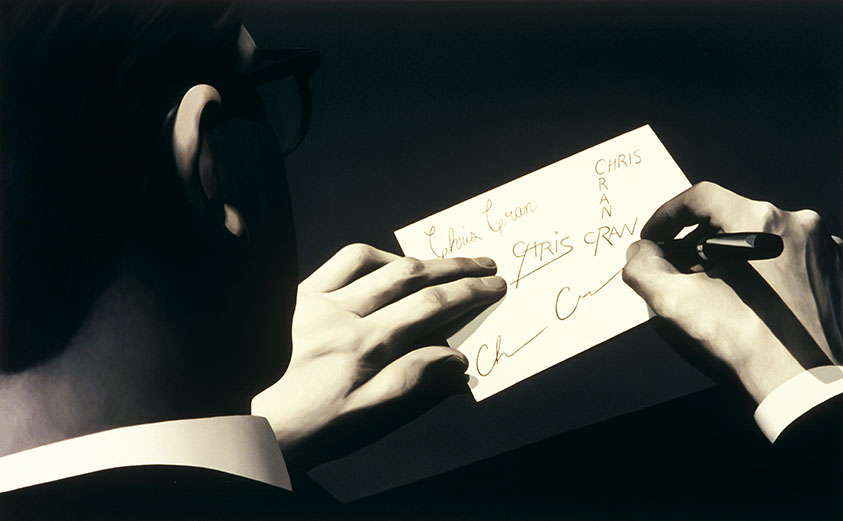

Chris Cran, Self-Portrait Practising Signatures, 1989. Organized by the National Gallery of Canada and the Art Gallery of Alberta as part of the NGC@AGA exhibition series, with the generous collaboration of the Southern Alberta Art Gallery.

Chris Cran, Self-Portrait Practising Signatures, 1989. Organized by the National Gallery of Canada and the Art Gallery of Alberta as part of the NGC@AGA exhibition series, with the generous collaboration of the Southern Alberta Art Gallery.

Cran has called art “a mute apparatus”—it’s not complete until a viewer applies thoughts, words and meanings to it. It can only speak when spoken to. The words “Sincerely Yours” necessarily preclude “Dear —.” They’re an invitation in, addressed to fans, long-time and first-time alike. When Cran came up with the title, he was thinking of signed photographs of movie stars that were mass-produced in the 1950s (so not really “sincerely” anyone’s, in fact).

Cran’s autograph appears in the last work in The Self-Portrait Series: Self-Portrait Practising Signatures (1989). In it, Cran’s writes various versions of his name, in curlicued cursive, block capitals and simplified minimalist construction of loops and lines. But the painting isn’t a self-portrait at all. Cran took the image he based it on from in a British publication made in the 1950s. He found it and thought, well, “Close enough.”

“Sincerely Yours” is also a signing off, signifying the end, but the prolific Cran isn’t nearly finished yet. After this exhibition wraps, he’s showing a suite of new paintings at Toronto’s Clint Roenisch Gallery, in a show cleverly called “Anon Anon”—the perfect punchline to end a retrospective with.