The 2017 Canadian Biennial—which opened at the National Gallery of Canada on October 19 and closes March 18—is the first of its kind to include artists from outside Canada. Their presence has the welcome effect of casting the NGC’s best, new(ish) Canadian art in a global light.

“It’s a Canadian perspective on what’s happening in the world,” said Marc Mayer, the NGC director, at the exhibition preview. He added that this biennial, which is the latest of the gallery’s semi-regular showcases of its recent contemporary acquisitions, represents “a broad gamut of art-making” and offers “worldly engagement” to its audience. Then, in a now-habitual gesture, he thanked the exhibition’s lead sponsor, the RBC Foundation, “notre partenaire fondamental.”

The first thing you see, after the curtain lifts, is Deep Waters (2014), by Montreal’s Patrick Coutu. It’s an aluminum cast of a rock ledge in Quebec. Isolated on the wall, it looks like a stray fragment from some computer simulation. Same with The Proposal of a Surface (Lichen Wall) (2013), a wallpaper designed by Canadian Zin Taylor that coats the octagonal antechamber in zoomed-in digital lichen. On a recent tour, Jonathan Shaughnessy, the biennial’s lead curator, described how Coutu and Taylor “steep us in forms of nature,” before we pass into the web of “social histories” woven through the exhibition.

Stan Douglas, Luanda-Kinshasa, 2013. High-definition video, Collection of the National Gallery of Canada. © Stan Douglas. Photo: Courtesy of the artist, David Zwirner, New York/London and Victoria Miro, London.

Stan Douglas, Luanda-Kinshasa, 2013. High-definition video, Collection of the National Gallery of Canada. © Stan Douglas. Photo: Courtesy of the artist, David Zwirner, New York/London and Victoria Miro, London.

Entering the first gallery, three different works command immediate attention: Qusuquzah, Une Très Belle Négresse #3 (2012), an excellent portrait painted by American artist Mickalene Thomas; Sitting Woman (2012), by the L.A.-based sculptor Thomas Houseago; and Casualties of Modernity (2015), an installation-plus-video by Kent Monkman, the well-known Canadian artist of Cree ancestry.

Each of these works “in its own way enters into dialogue with the past century of Western art,” Shaughnessy writes in his catalogue essay, “especially the period of modernism that defined late nineteenth- to mid-twentieth-century aesthetics globally.” The modernist period “remains a productive wellspring” for artists working today—particularly those who seek to dismantle its conceits.

Monkman’s Casualties of Modernity features a painted wooden sculpture—reminiscent of Picasso’s proto-cubist “African Period”—lying unconscious in a hospital room (which has been cleverly tucked into an alcove in the gallery). Monkman’s drag queen alter ego, Miss Chief Eagle Testickle, tends to the ailing historical corpus, which, we learn from a video on the wall, suffers from a “very serious infection of primitivism.” Modern art on life support.

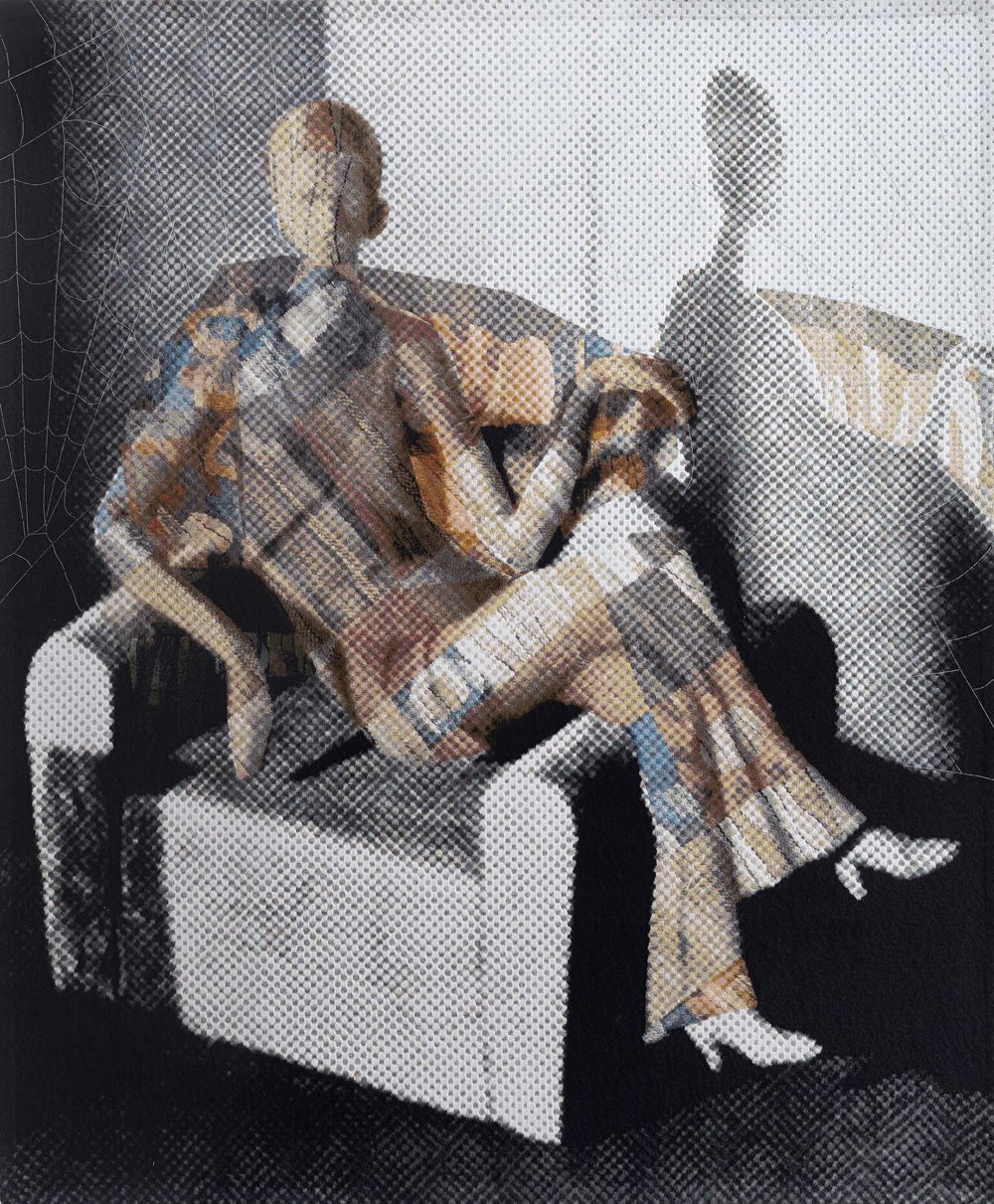

Shannon Bool, The Spinner, 2015. Cotton, wool, polyester, acrylic, viscose, metal and dye, 230 x 186.5 cm. Collection National Gallery of Canada. © Shannon Bool. Photo: Courtesy Daniel Faria Gallery.

Shannon Bool, The Spinner, 2015. Cotton, wool, polyester, acrylic, viscose, metal and dye, 230 x 186.5 cm. Collection National Gallery of Canada. © Shannon Bool. Photo: Courtesy Daniel Faria Gallery.

Modernist tropes collapse under their own weight in Houseago’s Sitting Woman (based on Rihanna’s November 2011 Esquire cover) and in Thomas’s celebratory portrait of her friend Qusuquzah, which mixes rhinestone glamour with the fauvist canon. “The women in my work throw up a pretty formidable barrier to the tradition of fetishization of black skin,” Thomas is quoted saying in the catalogue. “They look right back at the viewer with self-knowledge, demanding to be seen while creating the impression of seeing right through the viewer.”

“It would be nice to think about artists making worlds,” Shaughnessy said, as we walked past German artist Wolfgang Tillmans’ seductive image The Cock (Kiss) (2002). “When you don’t see your reflection in the world, you go about making a world that reflects you.”

No work in the biennial addresses the interplay of self and world better than Soundsuit (2015) by the Chicago-based artist and dancer Nick Cave. The suit (which also serves as the exhibition’s poster image) hails from a long series of wearable artworks that Cave has made and danced in since 1992—the first being made in response to the acquittal of the four Los Angeles Police Department officers who were caught on camera beating Rodney King.

Cave’s early Soundsuits were nearly monochrome, made of sticks and woven baskets. They can read as suits of armour, and Cave’s performances in them have been described as a way of processing the vulnerability of being gay and Black in America. Over time, the Soundsuits have become more playful, more colourful and ornate (this one at the NGC features a blue gramophone and a tree of knick-knacks). They’re now, in Shaughnessy’s words, “simply an affirmation of life.” Like Thomas’ Qusuquzah, Soundsuit is both a celebration and a template for resistance.

It’s fitting, then, to see the work of Cave and others meet a strong contingent of Indigenous artists from Musqueam, Nunavut and elsewhere. Artists such as Susan Point, Ruben Komangapik and Jamasee Padluq Pitseolak refuse to let their stories get swept into a global past, and use artistic practice to assert and celebrate their specific cultural sovereignties.

In the second-to-last gallery, Soundsuit finds an echo in Bookwus Ghost Mask (2012), by the legendary Kwakwaka’wakw artist and chief Beau Dick. In traditional Kwakwaka’wakw ceremonies, dancers wear ghost masks to visit the land of the dead. Dick himself danced Bookwus Ghost Mask in 2013, in the Walk for Reconciliation through downtown Vancouver, making the mask a living avatar of Indigenous rights.

Elsewhere in the exhibition, the Egyptian artist Wael Shawky uses antique marionettes to dramatize the Crusades. His epic, three-part video Cabaret Crusades (2010, 2012, 2015) runs for three-and-a-half hours and is based on Amin Maalouf’s historical study The Crusades Through Arab Eyes (1983). Shawky’s depictions of bloodshed are meticulous, and he rounds out the work with operatic digressions. (The first two parts of Shawky’s video are on view here, while the third is included in “Turbulent Landings: The NGC 2017 Canadian Biennial,” a satellite project at the Art Gallery of Alberta closing January 7.)

Wael Shawky, Cabaret Crusades I: The Horror Show File, 2010. High-definition video. Collection of the National Gallery of Canada. © Wael Shawky. Courtesy Lisson Gallery.

Wael Shawky, Cabaret Crusades I: The Horror Show File, 2010. High-definition video. Collection of the National Gallery of Canada. © Wael Shawky. Courtesy Lisson Gallery.

While this biennial succeeds in presenting “transnational” histories, it also shows us that the past can be difficult to confront. This is hilariously the case in Heavy Weight History (2013), a Spinal Tap–esque video by the German artist Christian Jankowski. The video follows a group of Polish weightlifters around Warsaw as they try to lift—by hand—the city’s historic monuments. The popular Polish sportscaster Michał Olszański gives play-by-play commentary.

“Here, it’s not about kilograms,” Olszański says, as the athletes try and fail to leverage a Ronald Reagan monument. “It’s about stability and Ronald Reagan being really firm.” When the sculpture doesn’t budge, Olszański concludes, “This is the weight of history—perhaps it overwhelmed them.”

Nick Cave, Soundsuit, 2015. Mixed media including gramophone horn, ceramic birds, metal flowers, strung beads, fabric, metal and mannequin, 284.5 x 150 x 122 cm. Collection of the National Gallery of Canada. © Nick Cave. Courtesy of Jack Shainman Gallery, New York. Photo: NGC.

Nick Cave, Soundsuit, 2015. Mixed media including gramophone horn, ceramic birds, metal flowers, strung beads, fabric, metal and mannequin, 284.5 x 150 x 122 cm. Collection of the National Gallery of Canada. © Nick Cave. Courtesy of Jack Shainman Gallery, New York. Photo: NGC.