From its superstar mayor Naheed Nenshi to its NDP premier Rachel Notley, Calgary has become one of the most diverse, cosmopolitan and politically progressive cities in Canada.

But the Calgary Stampede—still billed as the greatest outdoor show on earth, in true Western-maverick fashion—continues to have a very defined and singular aesthetic.

Growing up in that city, it became clear to me—through subconscious and more overt means—that blue jeans, cowboy boots and a cowboy hat were the most socially acceptable uniform for those 10 days of summer. This lesson was underlined one July morning in the early 2000s when my brother, during a summer job home from university in Montreal, went to work at a downtown corporate communications firm and was ostracized for failing to wear jeans.

So it has, in recent years, been interesting for me to see the ways that Stampede aesthetics have been reworked, redirected and reframed by contemporary artists.

In 2009, Calgary-based Blood artist Terrance Houle posed in a loincloth amidst a pre-existing Stampede-related sidewalk display, resulting in the photo series Saddle Up! In 2010, Vancouver artist Paul Wong shot video at the Canadian Rockies International Rodeo—a gay rodeo 45 minutes’ drive from Calgary in Strathmore—for part of his installation 2 Hot 2 Handle. And in 2013, Toronto-based Cree artist Kent Monkman made The Big Four, a work inspired by the complex history of First Nations incarceration and cultural preservation that intertwine in the Stampede’s Indian Village.

This year, 2016, also offers rich artistic reflections on Stampede and related aspects of Western culture. In a show that recently wrapped at Untitled Art Society, Calgary-based artist Nicole Kelly Westman and Vancouver-based artist Del Hillier melded glam-style western wear, wanderings around prairie roadways, and copious bottles of Budweiser into their project Presenting Two Left-Footed Loocee and Delvis Cache. In “Field Portraits of Contemporary Western Culture” at the Southern Alberta Art Gallery in Lethbridge, curator Wayne Baerwaldt brings together photography of cowboy culture—including pics by Saskatchewan cowboy poet Jon Bowie, himself a rancher. And in “Dark Horse,” currently on view at Stride Gallery (just 10 minutes’ walk from the Stampede Grounds), Yvonne Mullock presents what might be the world’s only horse-operated printing press—as well as monoprints of cowboy hats that she and the Arabian horse Shere Kaan made with the device, and video documentation of their process.

It’s this latter exhibition by Yvonne Mullock—with its physical reversal of the animal and the human, its leveraging (and destroying) of the iconic cowboy hat, and its humorous take on collaboration—that intrigues me the most at the moment.

“Dark Horse” is of a piece with Mullock’s past works, which also offer a dose of the wry and the whimsical, the chaotic and the collaborative: Last year, Mullock and artist Ann Thrale made a huge version of a game of pick-up sticks and dropped it in a dog park, documenting the results as Dog Pick-Up Sticks. In 2014, she created a teeny-tiny handmade version of the classic “white hat” that symbolizes not only Stampede, but Calgary in general (greeters wear them at the airport year-round, and “white hat ceremonies” are often held to welcome guests and dignitaries). And in 2013, she crafted what she called Beaver Made Ready Mades—bronzes cast directly from beaver-chewed sticks found in an inner-city neighbourhood near the Stampede Grounds.

Last week, I caught up with Mullock by phone to ask her more about “Dark Horse,” cowboy hats, and her Stampede must-sees.

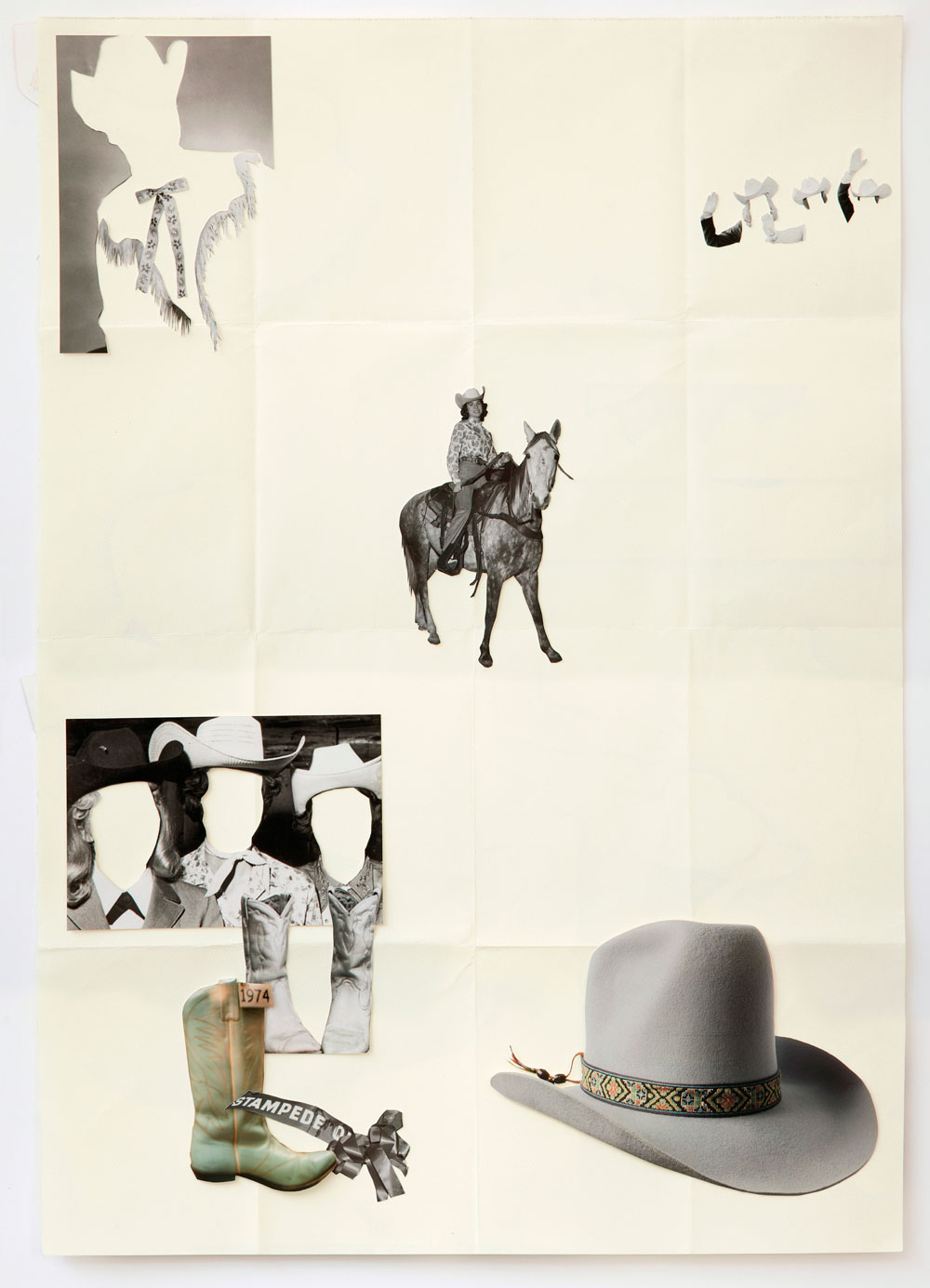

Artist Yvonne Mullock used photographs from the Glenbow Archives to create the image on the handout poster for her exhibition “Dark Horse” at Stride Gallery in Calgary. Image courtesy the artist.

Artist Yvonne Mullock used photographs from the Glenbow Archives to create the image on the handout poster for her exhibition “Dark Horse” at Stride Gallery in Calgary. Image courtesy the artist.

Leah Sandals: Why make art about the Stampede, or cowboy culture, or cowboy hats, yet again? What continues to compel you about this topic?

Yvonne Mullock: Well, I’ve had a long-term relationship now with Smithbilt hats. It started off with the commission of the small white hat [in 2014], and the work in “Dark Horse” is kind a continuation of that theme.

Also, when I did a residency at the Banff Centre recently, I started playing around with printmaking. I was very interested in the idea of the destructive act of printmaking, especially monoprinting, and how the outcome of that is really like a record of the printing process.

So Smithbilt offered me what I would call deadstock from the 70s for a new project. Another interesting kind of fact about the cowboy hat is that they have particular styles that are fashionable, and you can date them specifically by the depth of the crown, so certain styles stop selling after a while. I flattened some of these using a hydraulic press, and they turned out really interesting.

Then, I started to think about this idea of continuing to work with Smithbilt hats, but using them to print with. And then I thought about how the energy to flatten the hat could actually be replaced with the weight of a horse.

Artist Yvonne Mullock inks up a Smithbilt cowboy hat for the horse-driven printing press in the film documentation for “Dark Horse.” Photo: Noel Bégin. Image courtesy the artist.

Artist Yvonne Mullock inks up a Smithbilt cowboy hat for the horse-driven printing press in the film documentation for “Dark Horse.” Photo: Noel Bégin. Image courtesy the artist.

LS: So in a way, the work, to you, is more about the hat itself than what the hat represents?

YM: Yes, the hat is what I tend to obsess over in my work.

It’s such an interesting object—it has a utility to it in that it protects your head from the weather, but it is also a beautifully hand-made object. I have a background in making and sewing, so watching the process of these hats being made is what I was really fascinated with at first.

Also, the tools that Smithbilt uses to make the hats are still the original 110-year-old machines. There’s just this simple steam process to shape the hats, and they are all shaped by hand.

So it’s not about the Stampede per se—it’s about the bringing together of all of those things.

Also, the Stampede is an event that started off as an agricultural showcase, and I come from a long line of dairy farmers in Cheshire, England—no horses, really, but agricultural shows were something that me and my family went to a lot when I was growing up.

Overall, most of my work is research-based. I first came to Canada by coordinating a textile project, a quilting project, at Fogo Island Arts in Newfoundland. I really love meeting people who make things and understanding that in a first-hand rather than leaning about it in a book.

Arabian horse Shere Kaan and artist/handler Karly Mortimer exit the printing press in the film documentation for “Dark Horse.” Photo: Noel Bégin. Image courtesy the artist.

Arabian horse Shere Kaan and artist/handler Karly Mortimer exit the printing press in the film documentation for “Dark Horse.” Photo: Noel Bégin. Image courtesy the artist.

LS: So…. I’ve never heard of a horse-operated printing press before. Can you tell me more about how you developed this device and how it was used?

YM: Sure. The work was made in close consultation with artist Ann Thrale, who is gifted with wood. I brought her my rendering of it, and she added elements to it, like a pulley system.

The horse handler for the work was artist Karly Mortimer, who has been riding horses since she was tiny. I went out to her family’s ranch to look at and discuss the needs of the horse, so the device got a little bit adapted by her advice of what a horse is comfortable walking into.

Luckily, our horse—Shere Kaan—was very food-motivated, and he liked hay a lot.

A filmmaker and artist friend, Noel Bégin, also helped with the documentation—which was a relief, because then I could be in the film as the printmaking assistant. The horse is the printmaker, in my mind.

Installation view of “Yvonne Mullock: Dark Horse” at Stride Gallery, with the horse-driven printing press at right and resulting monoprints of cowboy hats at left. Image courtesy the artist. Photo: Nicole Kelly Westman.

Installation view of “Yvonne Mullock: Dark Horse” at Stride Gallery, with the horse-driven printing press at right and resulting monoprints of cowboy hats at left. Image courtesy the artist. Photo: Nicole Kelly Westman.

LS: What is it like to be a printmaking assistant to a horse? It’s an idea I find really funny.

YM: Well, I love printmaking, but I am a horrible printmaker. I can’t do editions for the life of me, because I am not a perfectionist and I get my fingerprints on it.

So rather than that being a battle, I thought, well, maybe I can just show the disruptive act of the printmaking, and then that in itself is the artwork.

I really like this idea, in my artwork, of losing control a bit—where I set up the limits, and then let the collaborative relationship or setup dictate the outcome.

In my mind, it kind of makes sense that the horse is the printmaker, because he’s the one exerting, he is the one walking on the platform of the press, and every time he does that differently, so the outcome is different.

Each print is different, too, depending on the hat and the material it is made of. Different materials absorb ink differently. Some are better quality wool than others.

Anyway, if you watch the film, you will see that I show the horse the print after each session. He’s got a really expressive face, Shere Kaan, and for the last print he actually kind of looks at it, then he nudges it. He’s a very likeable horse.

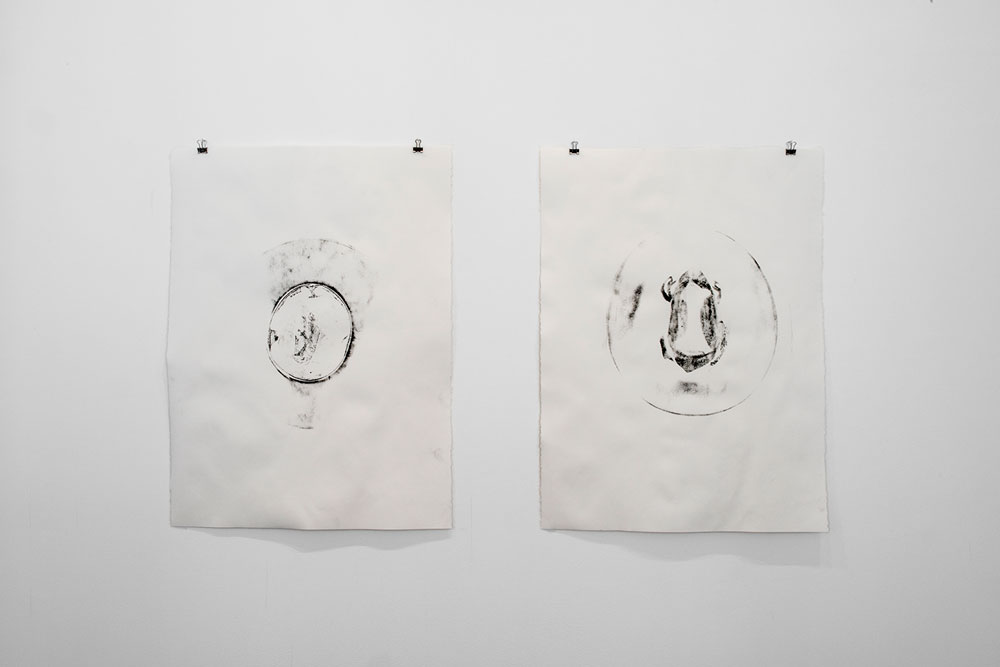

One of the resulting hat monoprints at “Yvonne Mullock: Dark Horse” at Stride Gallery in Calgary. Image courtesy the artist. Photo: Nicole Kelly Westman.

One of the resulting hat monoprints at “Yvonne Mullock: Dark Horse” at Stride Gallery in Calgary. Image courtesy the artist. Photo: Nicole Kelly Westman.

LS: You have collaborated with humans in the past, too, like on your rug hooking project Hit & Miss at the Esker, or that past work you mentioned with the quilters in Newfoundland. What about collaboration appeals to you, overall?

YM: I’ve done a lot of different kinds of residencies, and eventually, it seemed, the only way I could make something would be to work collaboratively. It is a process I really enjoy.

Also, I know that I’m not someone who has certain skills—and rather than being depressed about that, I can use the skills I do have and then meet people who have another set of skills, and learn from them, and come to a process of understanding what they do. I’m really fascinated with the history of how things are made. And I like to be involved with that making.

I guess part of the beauty is of working collaboratively is that it might take 30 years to get really good at making something—and when you collaborate, you get this wonderful gift or privilege of working with people who have that kind of skill.

Getting into a new mindset is also great. I’ve worked with saddle makers and taxidermists and scientists—the scientist’s process and rules are also fascinating.

An inked-up Stetson is readied for the printing press in the film documentation for “Dark Horse.” Photo: Noel Bégin. Image courtesy the artist.

An inked-up Stetson is readied for the printing press in the film documentation for “Dark Horse.” Photo: Noel Bégin. Image courtesy the artist.

LS: What else would you like viewers to know when they encounter or think about “Dark Horse” or a related work?

YM: Well, in “Dark Horse,” I am interested in this in the Stetson hat being a symbol of the West, and being an icon of romanticism about prairie life.

Also, there’s something here, specifically, about making in Calgary—we have hatmakers here that are still doing what they’ve done for a hundred years. That’s really amazing.

The image of a cowboy and his horse is also really interesting—that idea that the work of one is the work of the other. They work in tandem, intuitively.

Fashion and clothing is another aspect I always come back to in my work. This idea of a flat piece of cloth that can be shaped on the body still kind of blows my mind when I think about it.

Not so say that I’m blown away by what I do personally when I am sewing! But I think the fact that a piece of cloth can cover the human body and protect it is pretty awesome.

The way that intertwines with so many other things also intrigues me. The Stetson hat is traditionally made from wool, which keeps the head cool when it’s hot, and warm when it’s not. Wool comes from a sheep, and the natural lanolin and oil in it naturally protects the wearer from the rain. It is a resilient material.

Basically, there’s a lot of rich ideas here. I could talk about them for days!

LS: One last question: What do you like to do during Stampede?

YM: I love seeing the miniature horses. I think that’s in the first week of the Stampede. And after the miniature horses come in, there are the big shire horses. Then there’s the people who do gymnastics on top of the horses.

And my favourite part—not to sound cheesy—is wandering around the whole agricultural area. There’s a teaching tool of how cows give birth there every year. And there’s livestock, and different breeds of cows. I guess it’s in my blood, really.

“Yvonne Mullock: Dark Horse” continues until July 15 at Stride Gallery in Calgary. And the Calgary Stampede runs July 8 to 17.

This interview has been edited and condensed. And this article was corrected on July 7, 2016. The original included the term “paddle makers” rather than “saddle makers.”