With “The Shape of Colour: Excursions in Colour Field Art, 1950-2005,” his first major exhibition as curator of contemporary art at the Art Gallery of Ontario, David Moos has made a strong statement and done the Toronto art scene a great service. Moos is well attuned to the needs of our moment in history, and his return to the colour field is as contemporary as a show could get. A show as ambitious and as polemical as this deserves a complex response, not just a simple appreciation. We have to ask: what does the colour field mean to us today?

In the show, painters of the colour-field moment are bracketed by their predecessors, by their more-or-less recent successors and by contemporaries with whom they held a conversation. In the last two categories there is some overlap and blurring of generational groupings. Figures such as Polly Apfelbaum, who are very engaged with the traditions and problems of abstraction, seem closer in spirit to contemporaries of the colour-field painters such as Sam Gilliam and Anne Truitt than do the postmoderns, beginning with Peter Halley. The Canadian contingent, with central figures such as William Perehudoff and Jack Bush and peripheral ones such as Guido Molinari and Yves Gaucher, is also well chosen and strong.

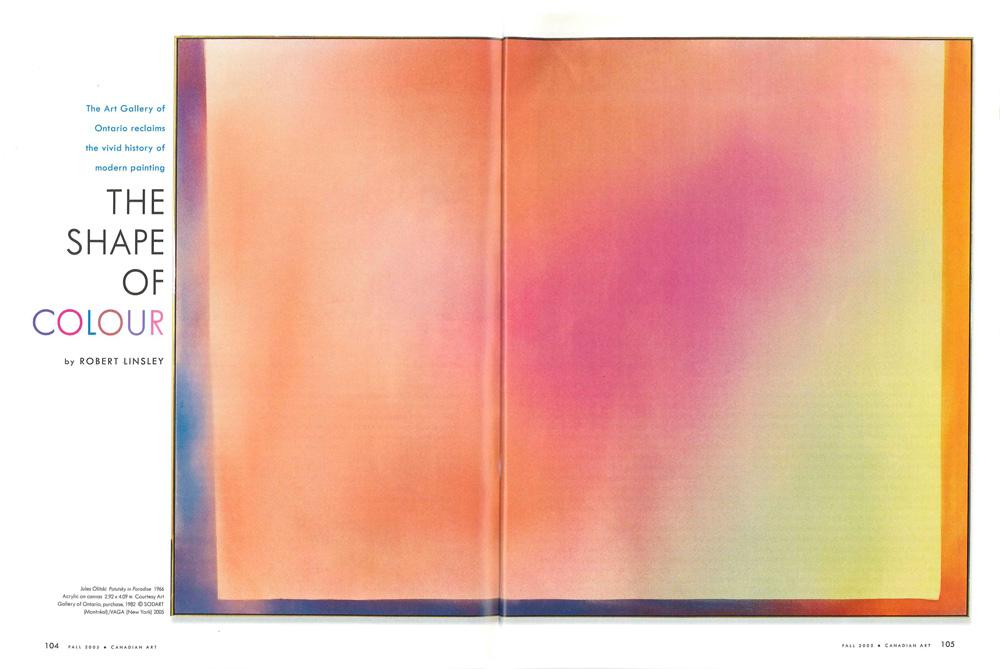

In the first series of rooms of the exhibition, Moos presents a magisterial procession of great works—by Clyfford Still, Robert Motherwell, Adolph Gottlieb, Helen Frankenthaler, Mark Rothko, Morris Louis, Ellsworth Kelly, Jules Olitski, Kenneth Noland and Fred Sandback. In these choices, the relationships they set up and the story that they tell, the curating is excellent, and that continues through into the next rooms with Robert Irwin, Agnes Martin, Frank Stella, Sam Gilliam and Polly Apfelbaum. In the last room, with work by Monique Prieto, Charles Long (with Stereolab), Sandra Meigs, Robert Youds, Odili Donald Odita, Anitra Hamilton, Christian Eckart and Diana Thater, the narrative falls off somewhat, but this only testifies to the difficulty of knowing the present—Moos does no worse than anyone else could do.

At the opening reception, Robert Youds was saying that it is the contemporaries who matter, that it is their interest and their engagement that have given the abstract colourists of the 1960s whatever ongoing life they have. In principle he is right. We need a reason to care about Louis, Noland and the others today, and only current art can provide that. But this relationship is based on exchange; historical art comes alive as contemporary artists find value in it, and contemporary art lives on the aesthetic capital it can extract from the past. This brings up the problem of influence, the term we use to stand for an aesthetic debt, and this is something that art since the late 1970s has had a very hard time with. One might live well on a legacy, or on credit, but in the economy of modern art, as in the real world, only growth through innovation can pay the bills. Moos may have started with a thesis about the importance of the colour field, but, whether he intended to or not, he has in fact presented a thesis about contemporary art and its relationship to the past.

I am struck by the general inability of the recent work to respond to its predecessors in any way but through quotation. This may indicate that colour-field painting has in fact never had any real relevance to art since the 1980s, but it is also likely owing to the standard conceptuality of art today. I remember when “conceptual” painting seemed like a great thing—clever, funny, reductive in a new way, responsive to the motions of thought. Now it seems the most conventional gambit of all. Here I have to reluctantly single out Anitra Hamilton. I have no doubt she is a serious and sincere artist, but when I hear that her colour choices are derived from military ribbons my interest begins to fade. Artists are not derivative, but artworks certainly have a pedigree, whatever the artist’s intentions are and no matter what they know or don’t know. The already existing example of Garry Neill Kennedy is enough to render Hamilton’s piece, which has its attractions, rather weak. But the bigger problem for Hamilton is that Kennedy’s send-up of abstraction, with its “critical” social and historical content, has now become a formula. The same objections apply to Charles Long’s piece, which takes up two familiar tropes of the 1980s, abstraction as decor and collective authorship. There was a time when it seemed liberating to assert that abstraction was impurely mixed with all kinds of social purposes and needs, or that formalist discourse left out too much of life, of the body and the mind. But now we know all that, and accept it, and we find that the qualities that made formalist abstraction interesting to begin with are still present and working.

Though Molinari and Kelly emerge out of a European tradition of abstraction, and Still is his own original, the rest of the work in the show is inconceivable without Jackson Pollock. And yet the only one among the later artists in the show who is obviously thinking about Pollock is Polly Apfelbaum. As such she is an anomaly, but a revealing one. Hers is the only recent work that foregrounds the relation between part and whole. This is not to say that the other works are not compositions of different parts, or that their details are not important or not attended to, but Apfelbaum is the only one who takes the relation between part and whole as an aesthetic problem. But if we look at the paintings of Louis, Noland, Frankenthaler, Olitski, LeWitt, Perehudoff, Robert Irwin, Frank Stella and Agnes Martin with open eyes, we can see that they do this as well, and also in response to Pollock. Here is a chance to break with canonical formalist history and observe that none of these artists achieved, or wanted to achieve, the all-overness or all-at-onceness that criticism once had us believe. They all fuss over details and minute particulars, and often that fussiness means that the work only achieves an illusion of unity or singleness, but the act of fussing is what makes the work. For example, in the current show, it is fascinating to see Noland carefully paint between some of the rings of his target, completely giving the lie to the concept of the one-shot painting, or to see the difficulties faced by Stella in fitting canvas over his shaped stretcher, difficulties he can barely resolve. Problematic today is that many works are finished products before they are even made. I don’t want to valorize spontaneity or process, or claim that works should not be fabricated by machine. The problem is an aesthetic one, and not reducible to a question of style. There is less place for unprogrammed experience when the space between conception and execution is narrowed. This criticism applies to any work that more or less adequately delivers a concept, and to any work that does more than that but is nevertheless routinized in execution.

The question can be approached in a different way through the brush stroke. Clement Greenberg stated explicitly that important work transcended the distinction between painterly and non-painterly. The brush stroke must be objectified, and there is no single right way to do this. We have to think of the brush stroke not as a personal trace, but as the atom or building block of a picture. Each of Louis’s long, wandering flows is a large brush stroke, as is each of Frankenthaler’s stains and each of Apfelbaum’s little coloured swatches. Much recent work follows minimalism in presenting a cleanly manufactured fabric. Again, this is not a bad thing in itself, but it fails to pick up what the colour-field painters have to offer by way of an inventory of possibilities for the articulation of form. All of which is a preface to the observation that the current widespread identification of the art of painting with the manipulation of paint, and all the textures and strokes and tactile effects that it can provide, is definitely not the way, but then neither is the unthinking surface of a Christian Eckart.

The art historian Shep Steiner, who contributes an essay to the show’s catalogue, is the first to see and discuss what seem like involuntary or barely managed details in colour-field painting. This is an important reading because it coincides with an emerging sensibility of the micro-feature, of what Duchamp, in his prescient way, called the infra-mince. I see the evidence of this new sensibility in Steiner’s review of Raoul De Keyser in Canadian Art (Fall 2004) and Barry Schwabsky’s review of the same artist in Artforum (Summer 2004). In both cases the critics encountered what looked like unformed places in the works, and were intrigued by the way that these incidents escaped evaluation. There is a blurred line between art and ordinary stuff; this is also the place where intention and accident are indistinguishable. Of course, neither intention nor accident really exists in any genuine work, but hesitations and corrections and messes and screw-ups of all sorts allow the artist to appear as an effect of the work in a new way. This is a continuation of the old modernist ambition to dissolve art into nature, which is really a way of using the trope of “nature” to reinvent the artist as something more than an ego. The ongoing necessity of this modernist program is not theoretical; it is a function of the intrinsic difficulty of making art at all.

The last room of the show contains a pretty broad range of work, and that of Meigs, Prieto and Youds in particular is as non-conceptual as one could ask for. These three artists constitute an important subgroup. Their work is basically narrative, and, like any engaging story, full of interesting characters, treated warmly yet ironically by their author. In Youds’s case this may be less obvious, but I think it holds true for his work in general. I support this work, but here the historical art on show itself takes up the role of critic, and says that abstraction works with formal qualities, not human ones, but therein loses nothing of social relevance, individual character or expressive value. Which leads to the observation that all formal gestures are rhetorical, meaning that there is no art that is not literary through and through. To give an example from “The Shape of Colour”: the salient feature of Louis’s pours is that they cannot be undone. From Cézanne to Matisse to the latest “painterly” painter, modernist painting was always a palimpsest of changes and corrections, of second, third and many thoughts. With Pollock, Frankenthaler and Louis, there is never any going back. We could say that time runs out with the paint, and so their method is a metaphor of mortality. Death is the end, both figuratively and literally, although the two are really the same. A trope, or rhetorical figure, is by definition a substitution and the place where meaning changes, and similarly the literalness of modernist abstraction is a way of avoiding an inevitable conclusion, meaning a repetition of the past, by finding a material fact that can stand in for death. And in art death is never the real death; death is only another trope, in this case for the self-invention of the artist.

One of the strongest tropes that Moos has threaded through the show is the empty space, the void. We find it in Motherwell, Louis, Stella, Molinari, Irwin, Martin and Hamilton, but most importantly and most impressively in Sandback. This is another point where we can productively veer away from mainstream modernist thinking. Whereas Greenberg claimed that the fundamental grounding condition of modern painting was the continuous, delimited and flat plane, in Sandback’s work the plane itself is an illusion, and this captures a profound truth. It isn’t flatness that matters, but the irreducibility of illusion, even including the illusion of flatness. I can’t help but associate Sandback with Gordon Matta-Clark; both artists projected illusionistic forms into three-dimensional space, a working path as yet untraced any great distance.

Potentials for the art of the present and future can only be found within existing practice—where else could they be? But not all practices are equally supplied with possibilities at all periods. In the future it will undoubtedly look different, but at this moment the contemporary work in the show seems to offer few. To my eyes, right now, Louis, Noland, Frankenthaler and, surprisingly, even Olitski look pretty up to date, but what is really at stake is the future, and how we can use the art of both the present and the past to get there. The times do not call for a painting that is conceptual, or postmodern, or that uses new media or technologies. This is a judgment of taste, a local and contingent response to what is overfamiliar, used up and academic. It goes without saying that any repetition of the modernist past would be a mistake, but what can give abstraction a future are unfinished aspects of that past. In my view that means work that conjures illusions in real space, that posits new relations between part and whole, that takes the boundary between nature and art into itself, that understands the rhetorics of form and does any or all of these things while simultaneously voiding subjectivity and foregrounding the self-formation of the work, including all the subjective decisions entailed. If that sounds too general or too theoretical, it is unfortunate but unavoidable. These conclusions are derived from my experience of “The Shape of Colour,” and from my own practice, but to have a broad relevance they must also have a certain level of generality. That generality is also a way of ensuring that new work looks new, that it doesn’t copy a style or a manner, but takes up fundamental questions. This is where conceptuality belongs: it should be dissolved in the preparation, not displayed in the work.

To look again at work that was so recently beneath notice naturally provokes thought about the history of taste, but also speaks to the more profound aspects of the development of modernism. At its inception, abstraction promised nothing other than a millennial change, a genuinely new future. As time passed, that future seemed to close down; but now it appears, however temporarily, however modestly, to be opening again. The great works included in “The Shape of Colour” provide a lot of indications for a renewed abstraction.

This is a feature from the Fall 2005 issue of Canadian Art.