“Jennifer” first appears as the carefully constructed persona she’s created in her artworks—someone cute and also creepy, donning both a grimace and a grin. In her naively styled drawings—which circulate in printed editions and artist books—she’s at once hopeful and heartbroken, and in a series of film shorts titled Jennifer Thinks (2009), she comes across as fanciful, but also sort of deranged.

Of course, Jennifer Bélanger’s also a real and relatable person—someone interesting and introverted who continues to make big contributions to the New Brunswick art community I’ve been a part of since arriving here in 2012.

It’s with both of these “Jennifers” in mind—their co-habitation and conflation—that I’ll break with the written convention of referring an artist by their surnames in this article.

“I’m an extremely private person,” Jennifer tells me. By way of an explanation, she describes having Mathieu Léger shoot the video for her project Mammas, don’t let your babies grow up to be artists (2016)—her creative-class riff on the old country tune.

“The first hour of filming was so uncomfortable! Even though it was just the two of us there, and I’ve known Mathieu for like 20 years! He’s one of my closest friends.”

Not something you’d expect from an artist whose work reaches out to complete strangers, probing public platforms with subtle alterations and deeply confessional statements.

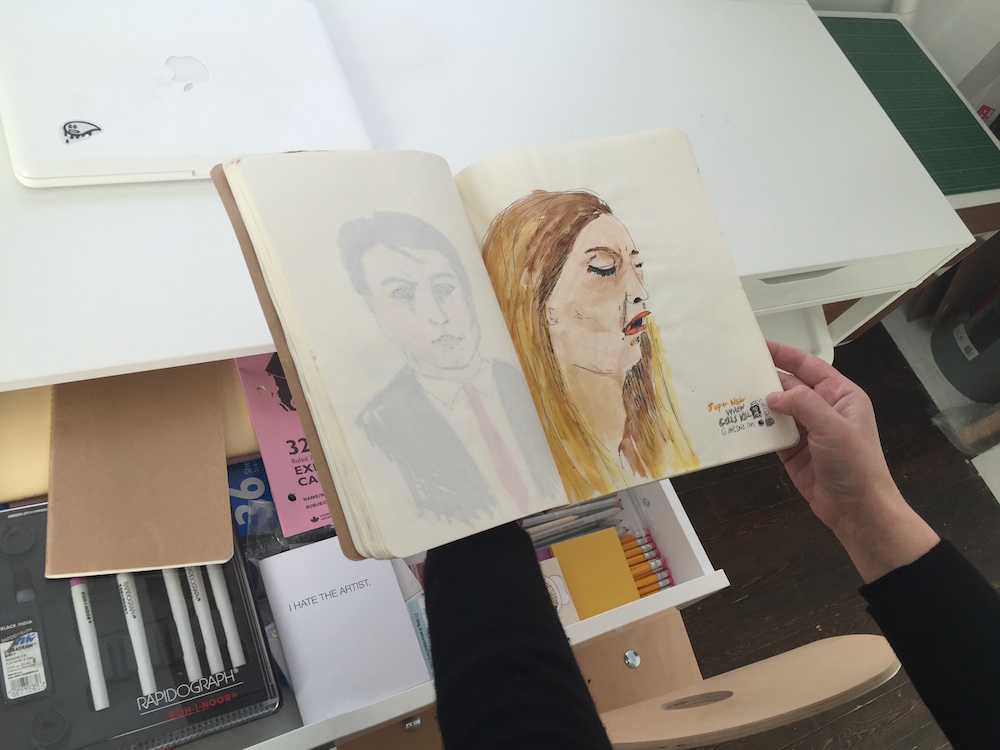

True crime drawings made during the Bélanger’s Jennifer’s Year of Drawing (2016–17) project. Photo: sophia bartholomew.

True crime drawings made during the Bélanger’s Jennifer’s Year of Drawing (2016–17) project. Photo: sophia bartholomew.

“Jennifer has had a difficult year,” reads the ad she placed in the Globe and Mail in 2011, for example. “[She] could use words of encouragement. Kindly send letters or cards to: P.O. Box #3, Moncton, NB, E1C 8R9.”

Mammas… screened last year as part of the Festival internationale du cinéma francophone en Acadie’s media-arts program, and along with a diaristic artist book, these videos bring together two years of reluctant daily practice, as Jennifer set herself the challenge of learning to play acoustic guitar.

An affection for old country prompted her to rewrite the ballad made popular by Waylon Jennings and Willie Nelson in 1978, altering the words in both French and English to warn unsuspecting mothers that:

Artists ain’t easy to love, and they’re harder to hold.

They’d rather give you a drawing than diamonds or gold.

…

They’ll never stay home, and they’re always alone.

Even with someone they love.

In the videos, she waves and blows kisses to an imaginary audience, adopting the gracious physical vocabulary of Loretta Lynn, played by Sissy Spacek in Coal Miner’s Daughter. Sparkling gold curtains glint from behind where she stands on stage, as countless hours of private performance are shared in a few minutes of performance onscreen.

She writes that her parents had bought her an acoustic guitar when she was 19, hoping she’d learn songs her father had written. When months passed with little improvement, she stowed the guitar away, leaving her hometown of Edmundston, in northwestern New Brunswick, to study visual arts at Université de Moncton.

Moncton’s been her home ever since. As part of a tight-knit group of young artists graduating with their BFAs in the late ’90s, she eagerly took up artistic practice and artist-run organizing—she first worked at Galérie Sans Nom, and later at Atelier d’estampe Imago, where she’s currently the director.

“You have to imagine…[when we were in school] we didn’t have access to the Internet, and the university’s library holdings were extremely limited.”

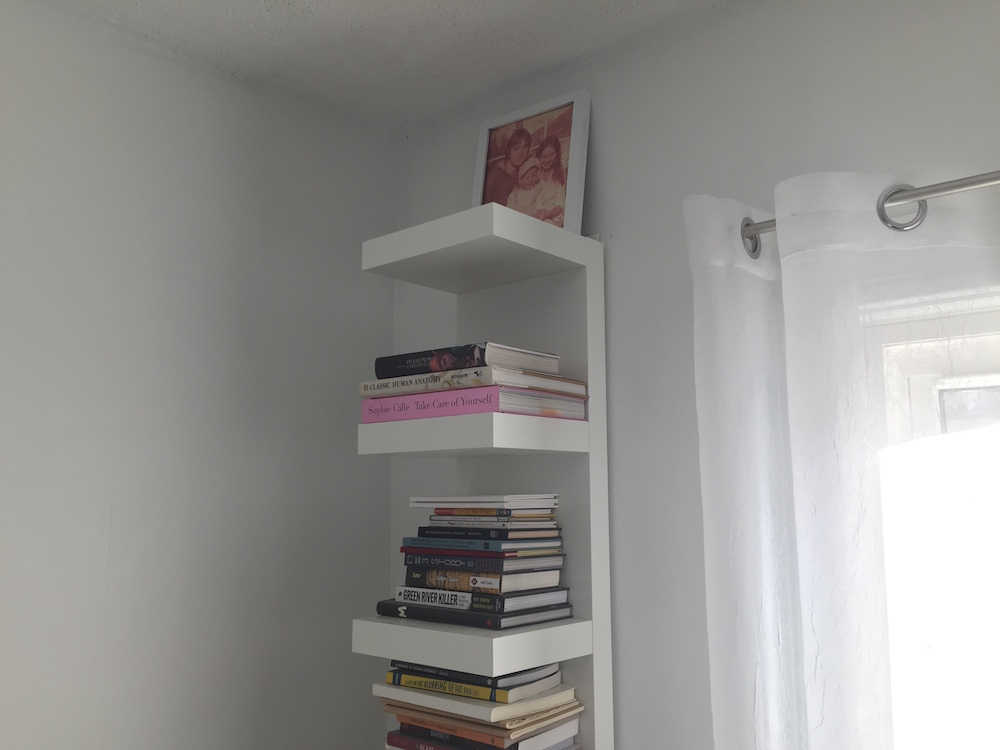

Books and a family photo in Jennifer Bélanger’s studio. Photo: sophia bartholomew.

Books and a family photo in Jennifer Bélanger’s studio. Photo: sophia bartholomew.

When I ask Jennifer about the artists who influenced her way of working, what she describes instead is celebrity gossip, teen culture, popular movies and television shows. Though, at some point, she discovered artists like David Shrigley and Sophie Calle, when she was doing her undergrad the U de M’s program was still very focused on work from the Modernist period.

“We had to take things from somewhere…” she explains, telling me how other friends developed their artistic approach by looking at comic books or historical paintings.

She went on to complete her MFA at NSCAD in 2008, and when she speaks about the years following graduation being difficult ones, she engages it with a sense of humour.

“Things were in a bit of a mess for me. It was like having a stranger going through my clothing drawers. I couldn’t find things…it was like all the things that used to be there kept going missing and getting replaced.”

We go on to talk about anger and secret sadness, and over the course of our conversation, I start to wonder if it might be easier to relate difficult things to strangers, rather than to the people we know and love.

This disparity between interior and exterior constructions comes up in a lot of her work—I’m thinking of works like Song and Dance (2011) and Bibelots (2008), which pair painful statements with readymade objects and images: I never really liked you; being with you is killing who I am; and, she would often daydream of getting hit by a car while jogging.

Together with June Main Street Interlude (2011), which posted one of Jennifer’s childhood photos to a Moncton billboard with the caption her mom would secretly follow her to the corner store, these works sort of read like something from Ken Lum’s Portrait Attribute series, but they’re more vulnerable, more personal.

Jennifer Bélanger working in her home studio in Moncton. Photo: sophia bartholomew.

Jennifer Bélanger working in her home studio in Moncton. Photo: sophia bartholomew.

Other projects of Jennifer’s source materials from mass culture—taking ownership of them by imposing a personal narrative, or repurposing bits and pieces toward some anonymous gesture of care. In Scrolls (2013–15), she uses phrases taken from a Google search for the 10 nicest things to say to somebody, and she places them on tiny scrolls that are then hidden in public places. In the shrine-like installation of Love, Jennifer (2013) and in her book Mes Hollywood Boyfriends (2012), she exaggerates perceived intimacy—writing to and about her top 10 celebrity crushes.

Until about 2008, Jennifer was also part of a collective—Collectif Taupe—working with Mario Doucette, Angèle Cormier and Jean-Denis Boudreau to stage disruptive performative gestures in public space, with a self-described interest in pranking people and in sparking social dialogue.

“We created the contexts we needed for the kind of work that we wanted to do,” she describes. They staged a fictional couple having public breakups across a variety of platforms in The Breakup Project (2005, 2008), and they assembled fake first-aid kits that could be used to get out of awkward situations in Emergency Kits (2006). They founded the fictional real-estate development firm Earthwork Development for their project Future Site… (2006), and in WalmArt (2006), the artists purchased prefab art from a large department store, and returned the items after swapping their own work into the frames.

Altering readymades in a retail context is also a strategy that Jennifer makes use of in her own work. In quiet, anonymous performances like Finish What You Started (2009), The Gift (2013) and an untitled series she began in 2008—adding narrative details to the scenes she found embroidered on second-hand woollen parkas—she sets out to “improve” found objects, working with and re-donating second-hand materials that invoke the visual vernacular of rural-domestic spaces, a sort of rural kitsch.

Lingering somewhere between kindness and meddling passive-aggression, these gestures ask questions about who and what has the authority to dictate something’s value.

Work from Index (2012) and other collected objects in Jennifer Bélanger’s living room. Photo: sophia bartholomew.

Work from Index (2012) and other collected objects in Jennifer Bélanger’s living room. Photo: sophia bartholomew.

Following the tradition of daily ritual and private performance that she’s set up through so much of her practice, in 2017, she’s set out to learn how to draw “properly”—completing daily drawings and re-taking a first-year drawing course in a process she’s described as funny and weird. It’s all part of completing a project supported by the Marie Hélène Allain Fellowship—an award named for a senior female sculptor, honouring the achievements of mid-career artists based in New Brunswick.

Visiting in her studio, Jennifer shows me some of these drawings. It’s only in the last few years that she’s set herself up in this upstairs room, in addition to the shared print studio she uses at Imago. Talking over coffee, in her kitchen, downstairs, I can’t help notice how much her home feels like her studio, how her studio feels like her home. The boundaries between art and life aren’t clear.

Her project Silkscreen on found object (2012) proposes that ART DOESN’T HAVE TO HURT, and when I ask Jennifer if she really believes that, she explains, “I often see students who were taught that art needs to be serious, searching for beauty, overly complex, and of course [they’ve been taught] the bigger, the better,” she posits. “I think art can and should be many other things, too.”

Some days, Jennifer resents this total integration of her self and her art—all of the personal challenges she sets out for herself in her work. As she says in her bio, sometimes she thinks that art ruined her life.

“Yeah, I feel like I’m always picking projects that make my life difficult,” Jennifer says, “but…I just can’t see myself doing anything else.”

sophia bartholomew is an artist based in New Brunswick who works with performance, language and other time-based media. She co-directed Connexion Artist-Run Centre in Fredericton from 2012 to 2015 after finishing her BFA at UBC.

This article is part of Canadian Art’s year-long Spotlight on New Brunswick series, created with the support of the Sheila Hugh Mackay Foundation.

Jennifer Bélanger in her home studio in Moncton. Photo: sophia bartholomew.

Jennifer Bélanger in her home studio in Moncton. Photo: sophia bartholomew.