I’ve been obsessed with archives as of late, no doubt in response to the strange climate of the year. If 2016 has reminded us of anything, it’s that history does not always move in a straight line. It bends, circulates, diverges and often forces us to trip back over ourselves.

Social-media platforms are inescapably archival—the thousands of postings linked to hashtags are proof of this. In architecture, a practice that currently plays out in complex relationships between physical and virtual worlds, social media is having an increasing impact on architectural education, history and practice at home and abroad.

“Architects need to start thinking of social media as the first draft of history,” argues critic and author Alexandra Lange in Dezeen. Many national and international architects are following this call.

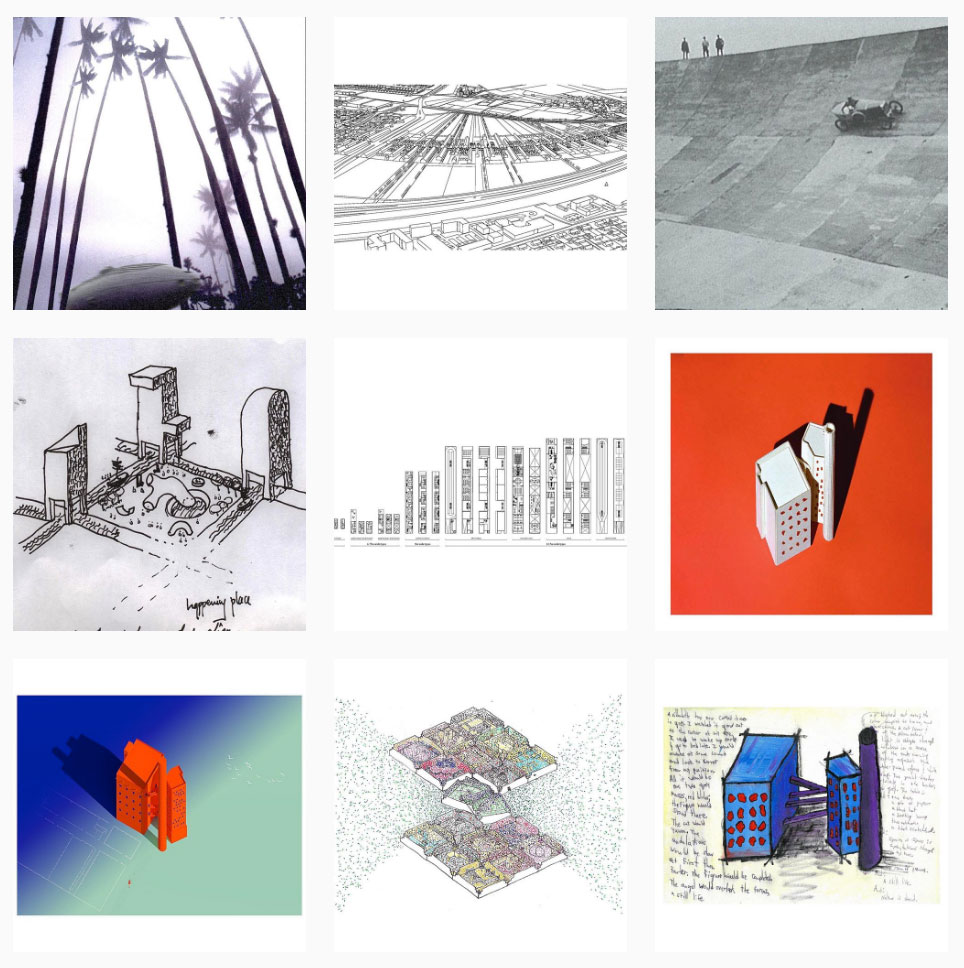

Among them is Toronto architect Adrian Phiffer, whose Instagram feed was recently named one of 25 accounts to follow by Archdaily. In his practice, Phiffer spans contemporary practitioner, educator and archival curator.

“I think the fact that we have all of these archival projects—from FuckYeahBrutalism to Archive of Affinities—has such a huge impact on how the practice is happening these days, because we are operating by accessing and looking at these archives as a way to project future projects,” Phiffer, who also works as a sessional instructor at the University of Toronto, tells me as we sit in the lobby of the Daniels Faculty of Landscape, Architecture and Design prior to his studio reviews.

Phiffer and I coincidentally spoke on the one-year anniversary of his Instagram account @officeofadrianphiffer. He considers the account, often featuring archival material, studio work and student projects, as an alternative to his firm’s traditional website.

Phiffer’s Instagram process involves subdividing work, past and present, into themes and “posting in a way that makes sense in continuity,” he says, while casually comparing it to a kind of extended PowerPoint. For Phiffer, teaching at U of T is a form of architectural practice with the account, reinforcing the relationship between inside and outside the academic environment, a further extension of that engagement.

In 2015, Phiffer was also a guest curator for OfHouses, a Tumblr edited by Romanian architect, curator and educator Daniel Tudor Munteanu to highlight dwellings often left out of conventional architectural histories.

Referring to his OfHouses series as a “tasting session of Canadian residential architecture,” Phiffer presented lesser-known works by Brigitte Shim and Howard Sutcliffe as well as Patricia and John Patkau, among others, to OfHouses’ international following.

For OfHouses, Phiffer combed through old editions of Canadian Architect, inspired by Paul Symie’s 1994 article “Houses in the City,” to reflect how Canadian architects have approached dwelling in both natural and artificial landscapes. The selected houses—built between 1944 and 1990, in locations from St.Vital to Montreal to Victoria—continue to speak to issues with city building in the age of condominium booms.

Phiffer hopes that his OfHouses archive offers case studies for “ways to densify the city without destroying the fabric.” Contextual concerns were fundamental in each project included—a natural landscape, a laneway, a parking lot—unlike many new structures in Toronto and other Canadian cities. Pointing to a large development looming menacingly over College Street, he notes: “There is no context.”

At McGill University’s School of Architecture in Montreal, Instagram is used as a method of capturing the present tense of architecture as opposed to the past.

Initiated in 2014 by architecture professor and Chair in the History and Philosophy of Science Annmarie Adams and researcher Bassem Eid Mohamed, @mcgill_architecture functions as a “backstage view” of architectural education—student projects, lectures, exhibitions, events and candid shots of studio life from students and faculty alike frequently appear.

A photo posted by #IMadeThat (@imadethat_) on Dec 1, 2016 at 6:01am PST

The account is often “taken over” by selected undergraduate, graduate and doctoral students who chronicle their daily experiences within the school. Currently, the school employs grad student Manon Paquet to spearhead the account, considering it an important investment.

It appears Instagram offers a primarily visual platform, one well suited for architecture.

“The image is first, then the caption,” Adams tells me over the phone. “We have thus learned a lot about ourselves through Instagram and our efforts to produce an academic ‘selfie,’” she concludes in a conference paper produced on the account.

Currently, the McGill Architecture account boasts 4,616 followers—the most out of any academic architecture account in Canada. Moving toward a primary focus on student work, many of the school’s posts are re-posted or re-grammed on accounts like @imadethat_ (11K followers), @next_top_architects (553K followers), and even @superarchitects (525K followers)—all accounts primarily followed by international students and practitioners who exchange projects through re-posts. (For those in doubt of their reach, note: the latter accounts have bigger Instagram followings than the Victoria and Albert Museum, and even the Whitney Museum.)

The visibility of student projects reaching a kind of “global audience,” as Adams says, is an important element of exposure for both students and the school. The McGill School of Architecture’s living archive of student work is inserted and folded within those of the larger discourse of global design while simultaneously offering a pedagogical time-capsule of 21st-century architectural education—remaining firmly planted in the centre.

The Rare Books and Special Collections Division of the McGill University Library, which contains the John Bland Canadian Architecture Collection, has also employed Instagram to begin visualizing its extensive holdings. The account @mcgill_rare began operating in February 2016, and has already amassed a following of 2,580.

Following in the footsteps of the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library (@fisherlibrary, 15.9K followers) at the University of Toronto, objects of interest, books, and pieces of pulp fiction from the broad archive are routinely posted. Such posts include a rarely seen rendering by Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh of the interior of a “House for an Art Lover” designed by her art nouveau–associated husband Charles Rennie Mackintosh.

The urgency in these social-media accounts lies in the methods used to articulate and visualize contemporary narratives and alternative histories. And they are drawing attention of traditional canon-builders, too—a means of extending said canon. The Canadian Centre for Architecture, for example, follows @mcgill_archicture. Canadian Architect follows @mcgill_rare, and the Storefront for Art and Architecture in New York follows both Phiffer and the McGill School of Architecture.

What does this new access mean for architecture in Canada? How many Likes will it take to make history? We’ll just have to wait and see.

Evan Pavka is editorial intern at Canadian Art. He has a background in design and architectural history.

Toronto architect Adrian Phiffer's Instagram feed was recently named one of 25 to follow by Archdaily. Photo: via Instagram.

Toronto architect Adrian Phiffer's Instagram feed was recently named one of 25 to follow by Archdaily. Photo: via Instagram.