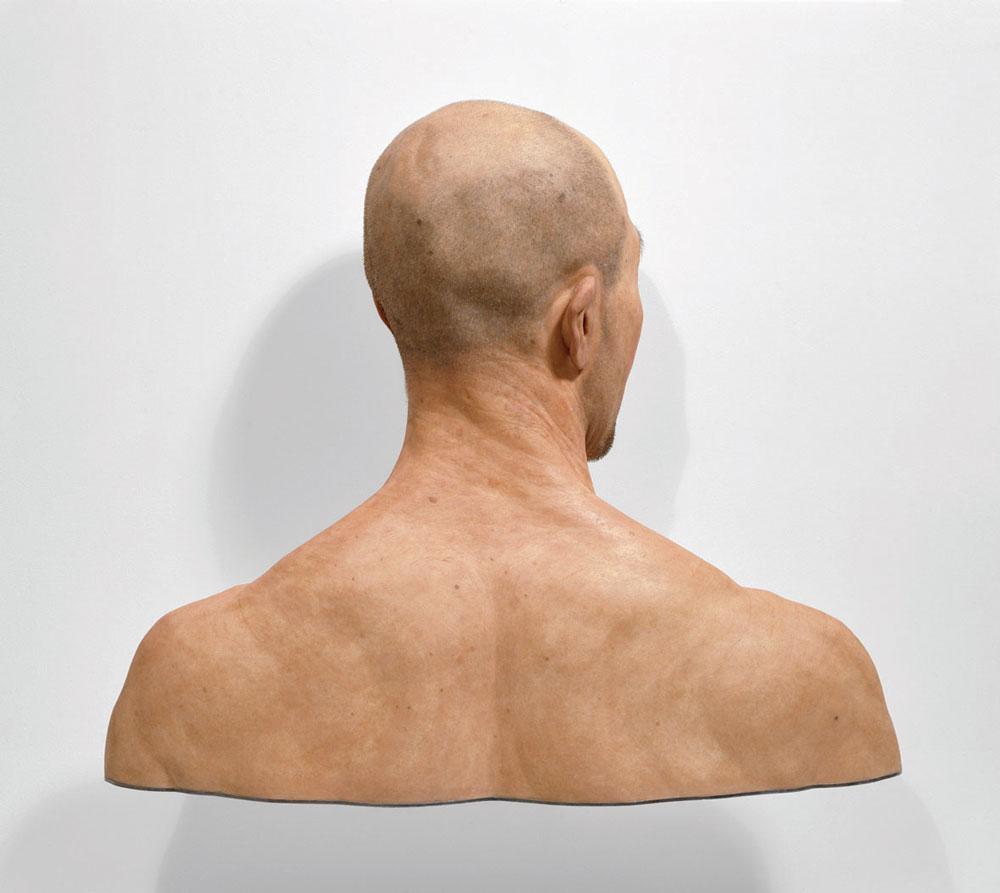

South African–born Canadian sculptor Evan Penny has been working for more than 30 years to create figures that both astound with their hyperrealism and confound with what might be called their post-realism. (Many of his works feature strangely distorted or flattened perspectives or scales.)

Penny is currently being fêted at Toronto’s Art Gallery of Ontario with a retrospective of roughly the last 10 years of his work entitled “Evan Penny: Re Figured”—which, since June 2011, has travelled to venues in Germany, Italy and Austria. Penny’s recent 10-foot-tall piece Jim Revisited, included as part of the European leg of the retrospective, was recently acquired by the National Gallery of Canada, and it will be installed there next month.

Last fall, Canadian Art assistant editor David Balzer sat down for coffee with Penny to discuss the retrospective, his long career—which has touched down significantly in the movies—and the effects of digital technology on how we see the world.

DB: Is this the first survey of your work?

EP: This is the first non-Canadian-generated survey of my work. I have had two surveys of my work in the past that were developed in Canada. This survey is organized by Daniel Schreiber from the Kunsthalle in Tübingen, just south of Stuttgart in Germany. He approached me around 2008 or so and proposed that he’d like to be the first European institution to mount a thorough exhibition of my work.

DB: What is your relationship like with the work you’ve made throughout your career? Obviously, it’s very detailed, evincing a lot of craftsmanship. Are you involved in preservation? Is there a process that needs to be engaged in terms of preservation?

EP: I currently use a vinyl material, a platinum-cured silicone. Other materials would be fabrics, human hair, horsehair—all of which are fairly stable. The platinum-cured silicones have a reputation for stability. Hair, of course, lasts a long time. Fabrics last as long as fabrics last.

DB: How much amassing or consolidation needs to happen for a show like this? Are your pieces scattered all over the place?

EP: It was a difficult show to mount. It was a roughly 10-year survey of the works—from 2000 to 2011—and during this period of time the works had been selling to institutions and private collections pretty much all over the world. It turned out to be a little difficult to be able to mount a coherent exhibition. We had to find lenders who were willing to part with the work for almost two years.

DB: How would you characterize this era of production or practice for you?

EP: I tend to divide my 30 or so years of work into three general periods.

The first 10 years was a period when I was working pretty much from direct observation with individual subjects, doing a series of standing, smaller-than-life-size figures.

The next 10 years was a period when I abandoned realism and overt figuration and was, I guess, more interested in exploring, or spreading out, the implications of figuration. The work was still body-based, but not overtly figurative. That period divided into multiple projects such as the monumental head fragments, the skin drawings and the clearly anamorphic pieces.

Then, in the late ’90s, I started moving into what I think of as this current phase, which initially began with the L. Faux project. On the one hand, it’s an attempt to bring all of my histories together. It takes the early figures, all the body-based explorations I did in the middle period, and the time I worked in the film industry—and it pulls them all together into one project. I think the film industry in particular made a significant contribution. It gave me exposure to materials, put me into a direct relationship with popular culture…gave me that perspective.

DB: Can you tell me more about your work in film? When did it start?

EP: The late ’80s. This was 15 years after I established my art practice; I was looking for work and was approached by a special-effects company here in Toronto, who worked for, principally, Hollywood-based, large-production, popular-release films. I worked on a part-time basis for that company for 15 years.

DB: What kinds of things did you do?

EP: Films we worked on were almost all of Oliver Stone’s work at the time, so in my case JFK, Nixon, Born on the Fourth of July.

DB: Were you making prosthetics?

EP: Basically it was a sculpture-effects shop, so anything that involved a kind of sculptural procedure. The specialty became prosthetic-makeup effects: so, character makeup, turning an actor into a president of the United States. Often it would be an old-age adaptation. In a war film, it could be body parts, limbs, wounds or whatever. In horror films or monster movies it could be something else. But primarily our effects were highly realist in their orientation.

DB: So how did this job specifically affect your art practice?

EP: Ironically, while I was working in the film industry, I was not doing realistic work in my own practice; I was doing more exploratory work. In a way, that worked quite well. There was enough of a gap between what I was doing, or what I was interested in doing, and what I was doing in the film industry. I kept the film industry very separate from my art practice.

That’s probably because I felt threatened. In lots of ways, you’re using a similar skill set in the film industry, but the value system and sense of priorities can be almost antithetical. So I was probably hypersensitive to that—and needed to maintain distance.

Then there was a moment in my practice when I thought, “Well, if I need to optimize, I need to stop compartmentalizing.” I now had these multiple histories that I kept apart from each other. I sculpted realist figures; I did interdisciplinary things—a period of work that was more lateral in its orientation. I just realized they’re all related and part of who I am.

DB: Jim Revisited: Is it life modelling? What is your relationship with this figure?

EP: The original Jim I rendered or modelled in the mid-1980s. The final was dated to 1985. Jim was a friend. That piece would have been done within the methodology I developed over that period of time. It was smaller-than-life-size, four-fifths life-size, a postured standing nude male figure rendered over many hours from direct observation.

The Jim Revisited piece, which I just finished earlier in 2011, uses that Jim as a starting point. Most of the work I’ve been doing over the course of the last few years has employed digital technologies to facilitate and explore how they can affect the thinking of the work. So this is a revisiting of that piece through my current orientation, specifically through the employment of digital scanning, computer manipulation and a CNC milling process.

Jim Revisited is about 10 feet tall. It was initially started from a scan of the original sculpture, a three-dimensional scan. It was then altered, skewed and distorted in a 3-D software program, and it was milled in a hard urethane foam: what I received back in my studio was essentially a foam copy of a model of this early sculpture. I re-sculpted it; used that as a base mould and completely reworked it; made another mould; and then cast it into silicone. There’s a lot of technical procedure there.

DB: So it’s like you’re a musician and you’re covering an older song.

EP: I’m riffing on my own work but using that as a kind of base, a starting point to explore the relationship I now have to the media and technology at my disposal.

DB: What is the significance to you of the piece becoming bigger?

EP: On a practical level, it’s one of the obvious opportunities that the scanning reproductive process affords you: to shift scale economically, in terms of labour. On a more banal level, it was an exploration of how large could I go and how comfortable I could be at a certain scale.

A point of interest for me in the digital 3-D scanning software was the spatial configurations I could come up with. My work prior to this has all been based on photography, on some kind of pictorial, perspectival principle. So any kind of distortion, even if it was, say, an anamorphic distortion, was still based on a pictorial principle—a progressive flattening of the image as it recedes in space.

With the digital scanning process, the way the object plays in space is very different. For instance, it couldn’t be a true anamorph, in the sense that there may not be a point of view where everything is undistorted. These pieces, as you move around them, stay in a state of constant flux.

I’m really interested in the idea of the unstable object, in how one sense of time works in the object and that these things stay in flux as you engage them. It’s a different kind of time structuring in my mind. I think with the digital, how we imagine ourselves in time has changed again. I’m not sure we fully understand how it’s affecting us, but I think we’re starting to comprehend ourselves quite differently, and oftentimes it comes into conflict with the photographic model we’ve now absorbed and taken for granted.

DB: In a way, though, these experiments in dimensionality, perspective and optics are time-honoured. Your anamorphic work might be compared to the frontally hidden skull in Holbein’s The Ambassadors.

EP: It’s a sign of one’s relationship to technology. That’s how I interpret that painting: a painting of men that commemorates the merchant class and the kind of resurgent power of the middle class and its relationship to technology. Even though it’s a skull, the fact that it’s anamorphic represents this relationship to technology. It’s related to the camera obscura. So it’s the possibility of seeing and imagining differently because of the technologies that we’re now using. The basic principle still applies.

DB: On another note, a more personal one, are there hauntings that happen when you come back to these pieces that you’ve made of people you know or have known?

EP: Sure. A piece like this obviously looks as much backward as it does forward. And what’s happening on multiple levels is the subject. There’s my own personal relationship to the original piece and to that subject. Haunting is, I guess, an appropriate word in this case, because Jim died some years ago. But then that work is also some of the most classically sculptural work I’ve done in a long time: its connection to statuary, to monumental public sculpture, is implied.

DB: Is Jim Revisited the largest piece you’ve ever made?

EP: Yes, and the largest piece I’m ever likely to make.

DB: Do you see, with this survey, a closing of the third chapter?

EP: Yes, something’s happened. It’s hard to know when you’re going through it, but definitely I’m going through a period now of reassessing that I haven’t felt the need to engage over the last 10 years. These last 10 years have been a remarkably productive period, where there was just a lot of momentum, both externally and internally. I had a backlog of ideas I wanted to explore and it just took this long to do it. At this stage, I don’t think I’m going to be making big moves; I’m not going to abandon this and start something completely different or anything. I don’t see that. But I do recognize that something is shifting; I’m rethinking what I’m doing.