In many ways, 2018 has been a big year for motherhood in the arts in North America. In March, Carmen Winant’s My Birth opened at MoMA, installing two thousand childbirth photos in a single gallery. In April came the widely viewed online doc Artist and Mother about Kenyatta A.C. Hinkle, Andrea Chung, Rebecca Campbell and Tanya Aguiñiga, sharing various dimensions of the rewards, and challenges, of occupying both the film’s titular roles today. In May, Sheila Heti’s novel Motherhood was released, offering a deep consideration of what’s at stake when some artists undertake the decision to become mothers. Soon, that book, and several others, prompted Lauren Elkin to write the Paris Review article “Why All the Books About Motherhood?” “What’s different about this new crop of books about motherhood,” Elkin wrote, “is their unerring seriousness, their ambition, the way they demand that the experience of motherhood in all its viscera be taken seriously as literature…. We have lacked a canon of motherhood, and now, it seems, one is beginning to take shape.” In August, new mom Cardi B won Best New Artist at the MTV Video Music Awards, saying, “A couple of months ago, a lot of people were saying ‘you know, you’re gambling your career. You’re about to have a baby. What are you doing?’ And you know, I had a baby, I carried the baby, and now I’m still winning awards!” In November, Cardi B also ruled the cover of W’s annual Art Issue, speaking openly in a related feature about her motherhood experience and its impact on her life and work so far.

These are just some of the highlights around arts and motherhood in 2018. Looking back over the past 12 months, it’s seemed nothing less than a watershed moment for many—a time when, to borrow from Elkin’s essay on recent books, the interior life of mothers is finally being taken seriously in wider arts and culture, and mothers are finally being taken seriously as artists by those who aren’t already moms. There is recognition that the intense historical labour of artists and mothers like Audre Lorde and Adrienne Rich and Mary Kelly have paved the way for this, of course. Consistent, long-time support programs like the nine-year-strong Artist Mother Workshops at MAWA in Winnipeg have also played a role in this surge. But there is still, this year, a sense of binding, of breakthrough—of something to celebrate.

And yet, I’d be lying if I didn’t say some part of me, this past year, often had doubts about the value of talking about motherhood and the arts, or about considering the past year as a big win on that front. There is the hard data to consider, and key questions of who benefits most: No matter how many of these books and artworks get made, Black mothers are still more likely to die in childbirth, and Indigenous mothers are still more likely to have their children taken by state authorities. #ParentingSoWhite—or dominance of parenting memoirs, books, stories, and narratives by white authors—is, as Nefertiti Austin has cogently pointed out, a very real thing, and as a white author and parent myself, I play a role in reproducing that bias. Writing in The Cut in November, Angela Garbes asked, “Why Are We Only Talking About ‘Mom Books’ by White Women?” and listed powerful “mom books” by BIPOC authors that have been largely ignored in the latest waves of supposed motherhood canon-making. Also this year, Kansas and Oklahoma passed legislation “that allows state-licensed child welfare agencies to cite religious beliefs for not placing children in LGBT homes,” reports USA Today, “a troubling trend for LGBT advocates” that is impacting LGBTQ moms and that finds echoes in Ontario’s attacks on LGBTQ-inclusive sex ed and Alberta’s gay-straight alliance controversies. And then there is the problematic of choosing, in this article at least, to focus on motherhood rather than on parenthood—a choice which excludes the many terrific and hardworking parents who do not identify as moms and who refuse to be constrained by colonial gender binaries.

Co-existing with, overlapping with and dovetailing with such doubts, critiques and concerns are many powerful stories, analyses and challenges from mothers and artists—often BIPOC and LGBTQ—who articulate how the historical and contemporary biases against mothers in art intersect with other forms of bias in the arts and society. When I hear these artists, I feel more strongly that there remain urgent reasons for me to try addressing art and motherhood in arts writing and reportage. Some curators, building on the work of many, are also framing motherhood and mothering as a many-gendered verb, and some gallery directors are newly providing needed institutional supports to caregivers. Studies continue to show that mothers, like other femme-identified folks, still tend to do most of the emotional labour in families, and mothers also tend to bear the most labour in terms of infant care and feeding. So this particular article intends to highlight some of the points a few folks have raised around art and motherhood in recent works, talks, interviews and conversations.

One of the people I have listened to regarding motherhood and making this past year, and who has spoken eloquently on these points, is award-winning Toronto-based Colombian artist and musician Lido Pimienta. In 2018, Pimienta continued to foreground the way that women in the arts will continue to lose out until motherhood is supported and integrated within the cultural sector.

“The future of the arts… is digital. But it’s also uncertain until the normalization of motherhood in the arts takes place,” Pimienta said in November at a Toronto Walrus Talks event on The Future of the Arts, with her baby strapped to her chest in carrier. “The representation of women in the arts depends on this.”

In that talk, worth watching on YouTube in its entirety, Pimienta also addressed the way that motherhood biases are intersectional, reducing status in different ways for different artists, and often seeming miniscule in the bigger global political picture. Yet she continues to advocate for institutional supports for mothers in the arts, among others.

“The future of art will be once we normalize mothers and family, but not in a cheeky, community-arts-type way,” Pimienta states. “The consensus that I have to make as a mother in order to be able to be an artist should not rest on my hands and my hands alone. Art institution venues and all places that cater and nurture art that benefit from me must create spaces for me and my children as well, so that I as a woman have the space to prosper.”

Secwepemc Nation artist and curator Tania Willard told me recently that her experience of trying to be in a big-city arts scene after the birth of her children was a huge challenge—one that, in part, drove her desire to create BUSH Gallery, “a conceptual space for land based art and action led by Indigenous artists,” as her website puts it.

“BUSH Gallery was many things but, for me, the collectivity of it and the starting point was grounded in Indigenous knowledges and practices which included families,” says Willard via email. Part of what was absent in the city, she found, after she birthed her first child, were spaces that were “trying to be inclusive of a world with children—instead of a separating approach we have in our work and many sort of daily activities.”

So many public and private urban spaces, Willard notes, are not conducive to or welcoming to children and families. “And the gallery was one of the worst places to have a baby with me, echoing white walls and baby screams seem perfect opposites to the quiet contemplative spaces galleries seem to demand,” Willard states. “Everything seemed easier when I was outside. The infrastructure of modern cities and towns is just so much a part of a patriarchal pattern of development, but outside my toddler could run around, and I had less anxiety about disrupting the ways in which people perceived the gallery to be this space of adult quietness. And of course, when I was growing up, all community events in Indigenous communities were full of families and children and babies, and dogs, even.”

Willard participated in a Breastfeeding Art Expo that toured some BC galleries over the past few years, facilitating related workshops at Adams Lake First Nation and Neskonlith Indian Band hall where participants made linocut prints and solar prints based on three First Nations sculptures that depict breastfeeding. “I have a background as an artist and a curator but breastfeeding was such an important part of raising my children,” Willard says in a video posted by the expo. She adds: “There might have been a question of like, well how do you make these two things, breastfeeding and art, go together? But for me, because of my personal experience and belief in how beautiful a thing it can be for our communities and our families… I certainly think for Aboriginal people residential school experiences really harmed our ability to think about our bodies in a way where we are sharing that nourishment.”

Even though there were some workarounds available when Willard was starting out as a self-employed artist-parent, she says the overall system was set up in a way that presumed artists have few attachments beyond art itself. “I breastfed during talks and curatorial briefs and had playpens during install—many creative ways to make it through,” Willard describes, “but I often felt alone and like I was asking everyone else to accommodate me instead of feeling like it was just a normal part of life.”

More galleries are welcoming breastfeeding and children and families of late, which is a positive thing, Willard explains. “Kamloops Art Gallery here always has a kids’ table at openings which is great,” she notes. “I have heard of galleries supporting parents by actually taking initiative and supporting childcare for symposiums. There’s residencies that have small apartments and welcome families like the IAIA in Santa Fe makes a point of doing.”

But even more institutional initiatives need to happen, even more spaces need to be more flexible, and even more core arts expectations need to change, says Willard: “In my experience, though we have come a long way through feminisms, we are nowhere near centering the practice of care in our creative work.”

Another artist and mom I connected with this year was Amy Wong, who is founder of the Angry Asian Feminist Gang. In September, I saw her (and her toddler Rudi) at a unique artist-caregiver studio pilot created by MOTHRA, a collective of artist-parents in Toronto. (Another MOTHRA residency is planned for June/July 2019 at Artscape Gibraltar Point.)

“You don’t expect to produce, you do what you can,” said Wong of her expectations for this fall’s weeklong MOTHRA pilot where Legos sat next to a studio table, movable walls were set up to make a small children’s nap area, and a bassinet was placed beneath a workshop table arrayed with an artist’s paints and papers. “It’s more about the experience of coming together and seeing how there could be an alternative model to things that we don’t see happening currently.”

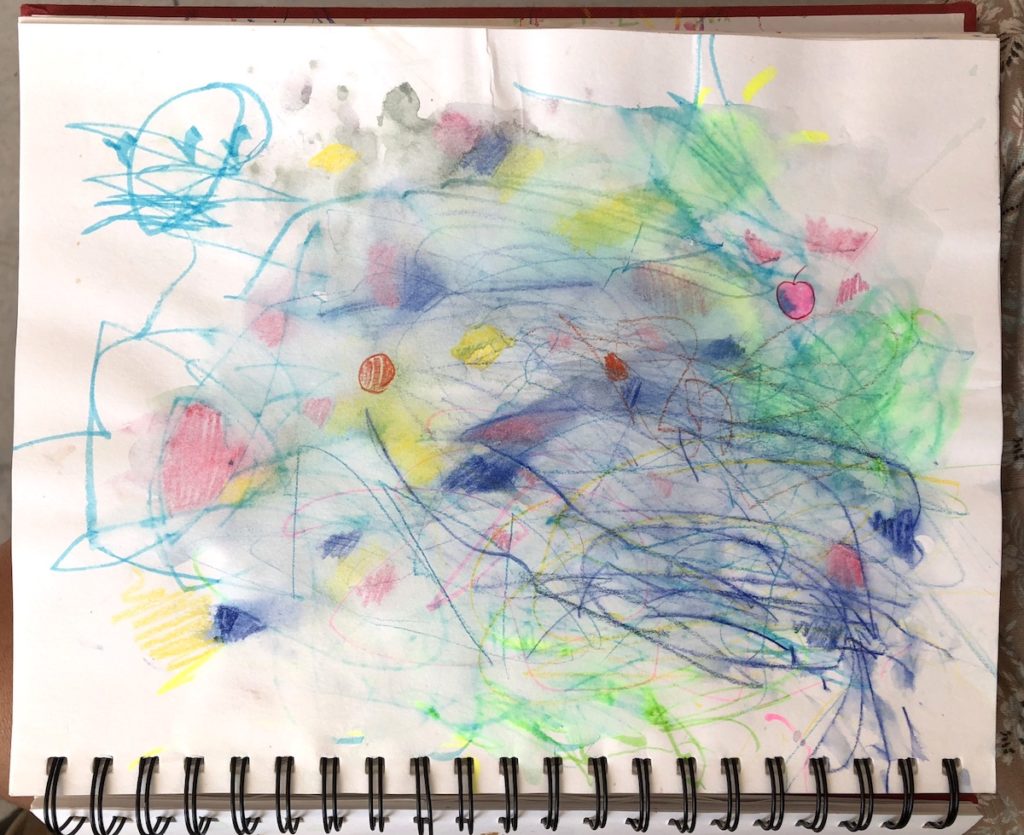

One of the ways Wong has kept a studio practice going since her child’s birth is by producing breastmilk watercolours with Rudi from time to time—a process that combines Rudi’s watercolour-pencil scribbles with her own fresh breastmilk for a sly spin on the canon of abjection and abstraction in painting. “Watercolour is also such a faux pas, a feminized medium,” says Wong. She jokes about the milk she uses, and produces: “It’s a miraculous, amazing elixir of life—and it’s also limited-edition right?”

Though Wong has, through Angry Asian Feminist Gang, helped advance public dialogues about bias against women in general, and racialized women in particular, she says having a child prompted an awareness of art-world biases against work that explicitly addresses motherhood: “You’re not supposed to talk about it, you’re not supposed to make work about it… ‘either get serious or do some real work’” is the unfortunate message, Wong says. Whether it’s by bringing Rudi to her collective’s meetings, bringing her kid on field trips when teaching (another form of care work, she points out) at OCAD, or participating in initiatives like the MOTHRA residency, Wong and others are hoping to change that.

Nova Scotia–raised artist Sheilah Wilson Restack has been working on art and parenting with her American partner, Dani Leventhal Restack, for some time, with their work offering a “continuing proposal for new forms of family, representation, queer desire, motherhood, and environment,” as Sheilah’s website puts it. In 2016, she released the first volume of Mother Mother, an occasional publication about different aspects of mothering and being mothered—including the first issue’s core question on the difficulties of being both.

In 2017, the Restacks’ video Strangely Ordinary This Devotion, which includes their daughter, Rose, was screened at the Whitney Biennial and the Toronto International Film Festival. “Strangely Ordinary This Devotion is a visceral exploration of feral domesticity, queer desire, and fantasy in a world under the threat of climate change. Utilizing and exploding archetypes, the film offers a radical approach to collaboration and the conception of family,” wrote Aily Nash, curator for Whitney Biennial. In 2018, the Restacks received a Canada Council grant to further research and develop artworks related to their experiences of lesbian parenting and queer families.

“It was important that the work be a mashup of movements between what our lives are like on a daily level and the potential for fantasy to coexist with or infiltrate or fracture the domestic,” Sheilah Wilson Restack says regarding Strangely Ordinary This Devotion and the now-in-progress project Future from Inside. “At one point several years ago, Dani said, ‘I want to inhabit a feral domestic’—just trying towards something that escapes the parameters that seem to exist around the domestic sphere. It tends to not be considered worthy of investigation or artmaking, and it also seems kind of stuck in outdated ideas of comfort or stability or tidiness. But in reality, it can very untidy emotionally, or even physically.” And, given the richness of the Restacks’ output, very generative for artmaking, too.

“This structural idea of movement between the domestic and our family reality, and the fantastical” was a big part of Strangely Ordinary This Devotion, and also will be for Future from Inside. Part of that movement for Future from Inside will involve a shift to Newfoundland and Labrador, where the Restacks plan to travel in summer 2019 for at least part of the filming. They are now making props for the shoot at home with Rose.

“I think we continually struggle individually and as collaborators and lovers with what family is, and what our practice is in relation to family, so this next sort of chapter is a further investigation of that,” Restack says. “Part of what we are interested in is what is it to show the reality of a lesbian relationship if you want a kid—it is nothing like what you are exposed to in grade-school sex ed.”

Institutions have a part to play in making the art world more workable for caregivers, and Mitchell Art Gallery director Carolyn Jervis has cogent things to say about how art institutions in general can improve on this front. Located at MacEwan University in Edmonton, the Mitchell Art Gallery is one white cube that has been trying to step up more for mothers, children and families as part of a wider, multi-pronged effort to increase participation and access.

In recent months, for instance, the Mitchell Gallery has been preparing for January 2019’s “Mothering Spaces,” an exhibition and symposium around Indigenous mothering curated by Becca Taylor. The exhibition features new work by The Ephemerals (Jaimie Isaac, Niki Little and Jenny Western), Faye HeavyShield, and Tiffany Shaw-Collinge and will explore, as the show description puts it, “individual narrative[s] of mothering while showing the communal impacts of mothering in public and within colonial spaces.”

To support the “Mothering Spaces” exhibition, the Mitchell Art Gallery has committed to providing funds not only for artists to travel to the exhibition opening and symposium, but for their children to travel to those events as well. “How we treat children greatly impacts how we treat women. Well, it impacts how we treat all caregivers of children—but since caregivers of children are most often women, the greatest impact it on women,” says Jervis. “So making sure we reevaluate how we think structurally about the work we do in art galleries is super important.”

This fall, Jervis also curated an exhibition, “Childish,” that included a collaboration and weekly workshops with Edmonton artist Kasie Campbell and her daughter, Mavi. Part of what made a 10-week Thursday workshop doable was that the Mitchell Gallery was flexible with start times given that both Kasie and Mavi had to catch the bus from Mavi’s school, and the bus sometimes ran behind.

Currently, summer artist residency applications for the Mitchell Gallery also explicitly include a space where artists can discuss their childcare needs, as well as other needed supports for practice. “I think there just has to be an understanding that we have to do things differently to support more people to participate,” says Jervis.

Curator Ginger Carlson of Truck Contemporary Art in Calgary has been thinking lately about the value of organizing exhibitions related to mothering as a many-gendered verb, as a kind of paradigmatic shift. “You hold me, as I fumble to emulate your care” was a fall exhibition at Truck Gallery that looked at “care, intimacy, vulnerability, and relationality through the lens of mothering,” says Carlson. This exhibition, and increasing number of projects like it, extend mothering into acts of care and being cared for in general.

The recent exhibition at Truck featured work by Farheen HaQ, Kablusiak, and Nicole Kelly Westman. For one work titled hamara badan, HaQ referenced her mother in a floor installation that her son activated in a one-night drumming and sound performance. “I wrap 140 pounds of red lentils (the weight of my mother) in a white shroud,” HaQ has written of hamara badan. “I ask witnesses to assist me in carrying my mother into the gallery space and to help me lay her down. The body is unwrapped and I attempt to wash away the narrow definitions of productivity and power that prevented me from seeing my mother when I was younger. I grieve the pain and losses incurred by internalized patriarchy in my lineage. I honour my mother’s body and the ways of knowing she holds.”

For Carlson, it wasn’t important that all the artists in the recent exhibition be mothers or parents, but rather that the actions of mothering and their legacies were thought through and brought into the curatorial process.“The exhibition, as it came together in terms of interests, took in mothering as a way of thinking around a methodology or an ethics, a verbing, a way of taking that idea of being in relationality and thinking about it in terms of how we relate to each other, how we might make exhibitions, how we can mother and care for artistic practice,” says Carlson. “I was thinking about vulnerability and intimacy, and caregiving—how we render visible those kinds of labours and honour them.”

To that extent, this particular exhibition echoes the ongoing, multi-authored online project Many-Gendered Mothers, and other such efforts. “As a curator, it’s interesting to think about those labours that aren’t as visible, and how we might offer space to cherish them—to reveal those relationships that are really important and intrinsic to artmaking, but perhaps not quite as expressed,” Carlson says.

Carlson emphasizes that the notion of mothering is far from simple or monolithic—and deserves further examination, extension and acknowledgement. “The idea of mothering or caregiving is something that everyone has a different relationship to,” she says, “so I think it’s something I’ll be thinking about in future as well.”

The idea of mothering or caregiving—and the multifaceted, differential realities of it, too—are something I will be thinking about in the future also. I hope that 2019 brings more supports for mothers and mothering in the arts, including centering of BIPOC and LGBTQ voices; consideration of how caregivers and caring of many kinds are neglected by arts institutions; and continued expansions of canons and countercanons to recognize lived experiences that have so long, too long, been neglected.

I personally regret that it took me becoming a mother to understand just how much our cultural institutions have been built around the myth and model of an attachment-free, always-mobile, fully self-funded and 24/7-available artist/creator. This model makes it very challenging for anyone with caregiving responsibilities of any kind—whether towards child or parent, partner or friend, self or kin—to participate in the arts scene, let alone succeed there. I also regret that it took becoming a mother to understand, in a new way for me, just how deeply sexism continues plays out in and beyond cultural institutions, and in different ways for different people. It is in connecting with artist-mothers and their works that these truths, for me, often continue to be illuminated, and it is through these connections, too, that my own biases and assumptions about mothering and creation continue to be challenged. I do hope that light of clarity, a light that shed much insight in 2018, is one that keeps shining in the year to come.

A breastmilk watercolour sketch made this year by artist Amy Wong and her toddler, Rudi. Courtesy of the artist.

A breastmilk watercolour sketch made this year by artist Amy Wong and her toddler, Rudi. Courtesy of the artist.