Generously supported by RBC

Marvin Luvualu António, Dispossessed Pt /1 (detail), 2016. Mixed-media installation Dimensions variable. Courtesy Clint Roenisch. Photo: Jimmy Limit.

Marvin Luvualu António, Dispossessed Pt /1 (detail), 2016. Mixed-media installation Dimensions variable. Courtesy Clint Roenisch. Photo: Jimmy Limit.

Marvin Luvualu António

Toronto-based artist Marvin Luvualu António creates self-contained structures that simultaneously invite, alienate and implicate viewers. His recent exhibition “Dispossessed / Pt 1” at Clint Roenisch in Toronto took its title from Ursula K. Le Guin’s iconic 1974 utopian sci-fi novel, The Dispossessed.

“I’m interested in science fiction,” Luvualu António explains, “because space is liberated and you can fill it with different languages and new systems of thought. It can shift, subvert or function outside of the white capitalist patriarchal ideologies around us. I want to create a world with my work, to treat each exhibition like a chapter in a book, because I think dipping into other worlds can be transformative and constructive.”

Within the exhibition, paintings, sculpture, video and a live python in an orange-acrylic box coexisted in a sandy ecosystem enclosed behind chain-link fence. Viewers could experience it only from a narrow path between the fence and gallery wall. It’s one of the ways that Luvualu António seeks to upset the dominant sense of order.

“When you realize that the structures we adhere to in our lives are just subjective units,” he says, “you then have the freedom to move them around, see their gaps and make them malleable. If you can employ this mode of thought it becomes less of a struggle to go into a space and make it your own. There’s so much to be accessed through the conflation of worlds.”

Anne Riley, that brings the other nearly as close as oneself, 2015. Denim markings on gallery wall Dimensions variable. Photo: Maegan Hill-Carroll.

Anne Riley, that brings the other nearly as close as oneself, 2015. Denim markings on gallery wall Dimensions variable. Photo: Maegan Hill-Carroll.

Anne Riley

Anne Riley moved to Vancouver in 2013, having grown up and pursued her undergraduate studies in Texas. For Riley, who is of Cree and Dene decent, moving to Vancouver marked a return and connection to place, but she found that the Vancouver art scene seemed to exist primarily in its head.

“Since moving back, I’ve been asking myself, beyond the intellectual, How do I embody my work? What kind of touch am I really desiring? In many art spaces you forget you are queer. You forget you even have a body.”

Riley’s that brings the other nearly as close as oneself, included in the 2015 exhibition “Every Little Bit Hurts” at Western Front, foregrounded touch, impression and embodied experience. The work’s primary components were a series of plaster casts of the artist’s hands grasping at each other in a pile on the floor, a wall drawing created by the artist rubbing, dragging and moving her body across the gallery wall wearing raw-dyed denim and a video of her actions on the gallery wall set to Donna Summer’s 1977 gay disco anthem “I Feel Love,” which was installed outside the exhibition space in the gallery’s bathroom.

“I’m interested in queer touch as a radical act,” she says. “It’s not always possible because of fear. But I’m also investigating first touch between mother and child. I have the same hands as my mother and my great grandmother.”

Krista Belle Stewart, Her Story, 2014. Short silent video played on public-art screens as part of the City of Vancouver’s Year of Reconciliation.

Krista Belle Stewart

Vancouver artist Krista Belle Stewart’s works change and shift over time. “I don’t ever feel settled about a work,” she says. “I still have a studio practice, but my studio is wherever I’m working. It’s on my laptop and inside the institutions I’m working within.”

Stewart regularly draws on materials pulled from collections and archives that she reframes and re-presents. Her work Seraphine: Her Own Story (2014), shown in different iterations at the Esker Foundation, Artspeak and Mercer Union, contrasts a 1967 docu-drama about the artist’s mother produced by the CBC with her mother’s 2013 testimony for the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. In different presentations the sometimes re-edited source materials played in separate rooms, on opposite walls of the same room, and side by side on the same wall—a strategy that, for Stewart, responds to the space of the gallery while reflecting her evolving relationship with the materials.

Similarly, her installation Indian Artists At Work (2016), which reproduces the title page of ethnographic photographer Ulli Steltzer’s book of the same title, imbues the grey-monochrome original with colours inspired by Indigenous Modernists in wall works that repeat the page in rigorous grids of paint and vinyl. Recent showings of the work at Presentation House and the Vancouver Art Gallery included collages and paintings by Leon Polk Smith borrowed from the VAG collection, responding to the colours in his works and, in the case of the VAG show, breaking the grid to incorporate the influence of the past on a critical present.

Nicole Kelly Westman Rose, Dear (detail), 2016. Mixed-media installation. Dimensions variable. Courtesy. Walter Phillips Gallery. Photo: Jessica Wittman.

Nicole Kelly Westman Rose, Dear (detail), 2016. Mixed-media installation. Dimensions variable. Courtesy. Walter Phillips Gallery. Photo: Jessica Wittman.

Nicole Kelly Westman

“I work through a lot of my regular human things as an artist,” says Calgary-based artist Nicole Kelly Westman. “I’m interested in exploring the permeability of the political through the personal.”

In her ongoing project Rose, Dear (2016–), originally commissioned by the Banff Centre’s Walter Phillips Gallery, Westman explores the largely abandoned ex-mining town Wayne, Alberta, through embodying a ghost that is said to haunt its lone hotel. The narratives of the town, hotel and ghost collapse into Westman’s own life through the inclusion of personal memory, quotation and, in the most recent iteration of the project at Gallery 44 in Toronto, the addition of a sculptural work engraved with the text of an unsolicited email she received critiquing the original installation of the work in Banff. For Westman, history is never fixed, and the structures of narratives and artworks continually evolve over time.

In From what I’ve found there were no truths, there were no lies (2013–14), for instance, Westman films a microfiche machine as she searches for information on a car accident that killed her grandfather and seriously injured her grandmother in 1965. In the archives, she found only two brief mentions of the accident, one of which misinterpreted her grandfather’s Metis last name of Mercredi as the Irish McCreody. This theme of identity slippage is doubled in the film’s voiceover, addressed to Westman’s grandmother, who when hospitalized in old age mentally returned to her hospitalization 50 years earlier, mistaking Westman for her sister and re-narrating her young life, including the accident and her recovery.

Anne Macmillan, Lures (still), 2015. Digital animation 6 min 21 sec.

Anne Macmillan, Lures (still), 2015. Digital animation 6 min 21 sec.

Anne Macmillan

Halifax artist Anne Macmillan uses technologies of vision and mapping to explore the natural world, working to complicate our understanding of both nature and the tools we use to observe it. In her ongoing series Little Lake (2012–), Macmillan swims the perimeter of each of 20 lakes named “Little Lake” in the Halifax area, tracking her swims with photographs and GPS. In the resulting documentation, Macmillan uses the points of the GPS recording to structure and spatially map her writings on the swim, while also contrasting the official perimeter of the lake defined by government documents and satellite images with the perimeter as it can be experienced by a body—with edges altered by fallen branches, changing water levels, erosion and vegetation.

Many of her works use 3-D modelling and animation to examine the distant or microscopic: “I’m interested in thinking about ideas of proximity,” she says. “The space between a thing and myself can become collapsed digitally—there’s a loss of information in this process, and there’s an asymmetrical relationship.”

In her video works Walking with Worms (2014) and For the Trees (2013), the act of modelling takes on metaphoric value as a form of forced structuring—foregrounding the distancing effects of technology and erasure of bodily presence. Despite the hyperreal images presented, this enhanced vision leaves only a hollow shell, and her subjects vanish upon close observation.

Steven Leyden Cochrane, Screen Wall (detail), 2015. Mixed-media installation. Dimensions variable.

Steven Leyden Cochrane, Screen Wall (detail), 2015. Mixed-media installation. Dimensions variable.

Steven Leyden Cochrane

“I’m interested in responding to gallery architecture, to make us more aware of it,” says Winnipeg-based artist Steven Leyden Cochrane. “But I’m also drawing on home decor. I’m investigating how the placement and arrangement of objects gives us cues for how to navigate a space and what its purpose might be.”

Cochrane performs spatial displacements and disruptions within the gallery, often superimposing domestic and garden motifs reminiscent of his home city of Tampa, Florida. His multipart investigations of concrete screen walls, a common landscaping material in suburban Florida, have been recently exhibited in different configurations at Truck in Calgary and Negative Space in Winnipeg. Cochrane explores the screen wall from memory and feeds these recollections into software that interpolates and scrambles their decorative motifs, creating skewed designs that he casts in concrete, cuts in foam and reinterprets through printmaking, photograms and video.

In a recent show at the RAW: Gallery of Architecture and Design, Cochrane presented a series of concrete screen walls in a gallery painted green-screen green, which he livestreamed with a chroma key replacement within the exhibition: “Although it doesn’t look like it, I’m really indebted to the work of first-generation institutional critique artists, but now, 50 years on, I feel that I can deploy these gestures a little more playfully. I like to play with the idea of the gallery being this magical, ‘neutral’ space that can become anything. I like to explore it, though fundamentally I’m critical of it.”

Felix Kalmenson, A Line is Not a Line (still), 2015. HD video 10 min 55 sec.

Felix Kalmenson, A Line is Not a Line (still), 2015. HD video 10 min 55 sec.

Felix Kalmenson

“I’m interested in the long view, in looking at the way narratives of a single place are often incompatible,” says Toronto artist Felix Kalmenson. “When I uncover and present diverging truths, I want to use them as a way of reading our contemporary situation. History is constantly being rewritten.”

Kalmenson’s research-based practice examines abstract contemporary forces, such as capital, big data and colonization, through the concreteness of architecture and landscape, identifying sites with complex histories and distilling them into parables for understanding the world. His installation Centre for the Interpretation of Water and Power (2014) uses video and found objects to investigate the use of water as both a consumable and hydroelectric resource in Blanca, Spain, while exploring the exploitation and manipulation of these resources by political bodies to reproduce other structures of power.

Kalmenson recently returned to Saint Petersburg, the city of his birth, for a residency organized by Russia’s National Centre for Contemporary Arts, a trip he had previously thought impossible because his family’s citizenship was revoked when they left the Soviet Union. Drawing on a family video recorded shortly before they left, Kalmenson created the two-channel video work Neither Country, Nor Graveyard (2017).

“I used the home video as a guide,” he says. “I’d been gone so long I had to interact with the city as a tourist. I made a shot-by-shot recreation of it. It became a way to re-inscribe myself onto the city, which has changed so much and not at all. The corrupt powers are just in new administrations and bureaucracies.”

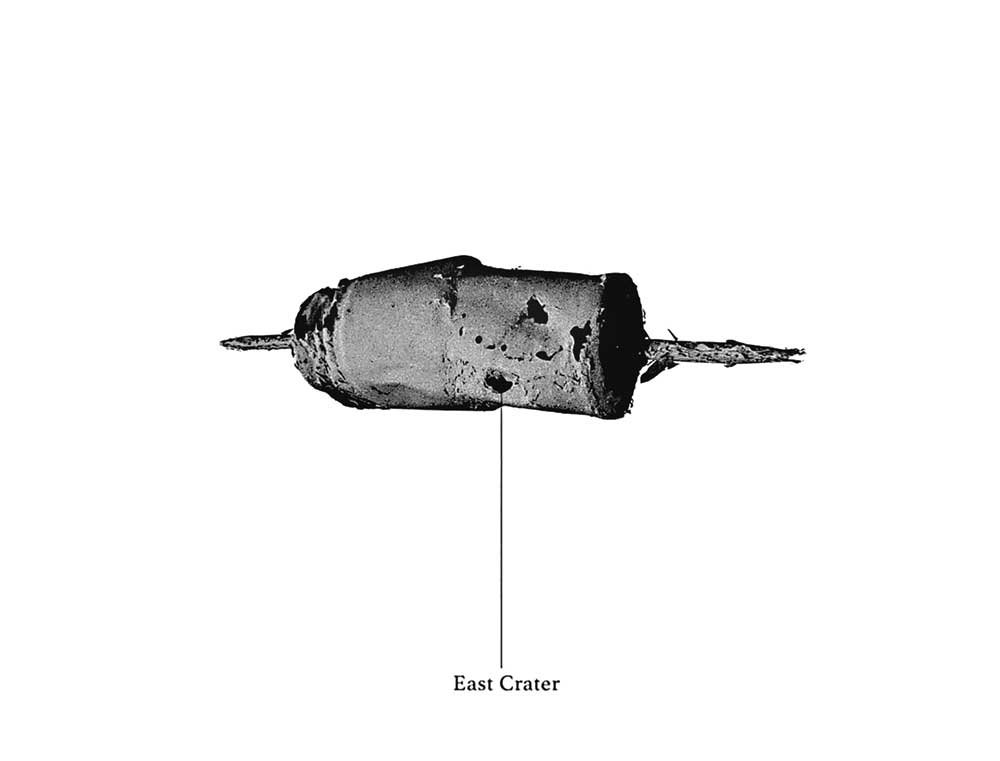

Installation view of “Past Is Prologue” at Western Front, Vancouver, 2011. Photo: Kevin Schmidt.

Installation view of “Past Is Prologue” at Western Front, Vancouver, 2011. Photo: Kevin Schmidt.

Sophie Bélair Clément

Negotiations of artistic license are at the core of Montreal artist Sophie Bélair Clément’s dialogic practice. Transposition and transferral are recurring motifs across media—from having an orchestra tune its instruments in harmony with the hum of a Dan Flavin fluorescent work to inviting fellow artists to participate in her own solo exhibitions. Bélair Clément’s recent exhibitions, including shows at the Leonard and Bina Ellen Art Gallery and Galerie des arts visuels Université Laval, have taken the form of collaborative projects in which she extends invitations to an interdisciplinary group of contributors.

“These invitations are becoming a big part of my work,” she explains. “I never use the term curatorial to describe my activities—I don’t produce interpretation—but as an artist I like using the exhibition as a place of dialogue.” In a similar mode of colloquy, Bélair Clément’s untitled exhibition at Vancouver’s Western Front examined the history and archives of the gallery, focusing on a 1973 video recording of early members describing its origin. She separately recorded six early members’ recollections of these events, presented alongside the original film on five monitors.

“To juxtapose all those voices reveals the fiction of the collective space—everyone is talking about the same events, but there’s no consensus. I think the same thing is happening in the collective shows I create. I’m not creating a community that agrees, but I’m still interested in putting them in conversation.”

Nika Fontaine, Schnell schnell #20, 2015. Glitter on canvas 1.5 x 1.2 m.

Nika Fontaine, Schnell schnell #20, 2015. Glitter on canvas 1.5 x 1.2 m.

Nika Fontaine

Montreal- and Berlin-based artist Nika Fontaine has a fascination with death and spiritualism dating back to her childhood—themes that recur across her paintings, sculpture and photographic works. Fontaine balances a genuine spiritual investigation with glam-rock garishness. Her work Pimp My Ride to Heaven (2014)—a heavily decorated, velvet trimmed, LED-illuminated, music-emitting coffin—is both a celebration of her former masculine identity and a marker of the beginning of her transfeminine life.

“Spirituality is at the core of my practice,” Fontaine says, “but decoration and kitsch are other important aspects. I want to use these to create something over the top.” Fontaine’s paintings negotiate the influence of her great-uncle, Plasticiens painter Jean-Paul Jérôme: “I was always surrounded by his paintings as a child. They are very beautiful, well-composed and classical Modernist works—but they made me want to create something more active and challenging to viewers, something aggressive. I love playing on the edge of good and bad taste.”

Fontaine’s Accelerators Volume I (2015), of which one piece received an honourable mention in the 2016 RBC Canadian Painting Competition and was recently exhibited at Joyce Yahouda Gallery in Montreal, is a series of colour-field glitter paintings intended to accelerate the meditative process for the viewer, functioning as both an aesthetic object and reflexive tool. The works, which are reminiscent of both galactic nebulas and Abstract Expressionism, simultaneously transcend and celebrate the materiality of glitter, employing it as a signal of kitsch and a medium for transcendence.

![]() Andrew Buszchak, Beacon (stills),2015. Documentation video of office building with automated fluorescent lights and binary code 9 hr. Photo: Scott Portingale.

Andrew Buszchak, Beacon (stills),2015. Documentation video of office building with automated fluorescent lights and binary code 9 hr. Photo: Scott Portingale.

Andrew Buszchak

Shortly after graduating from NSCAD University in 2009, Andrew Buszchak, now based in Guelph, moved to Edmonton and began working to understand the city through looking at its materials, infrastructures and languages, as well as personal and intuitive practices of walking and collecting. In Pulse Points (2012), he became interested in a city document related to the planned redevelopment of Edmonton’s Boyle Street neighbourhood, and inserted passages of this official language of gentrification into disused city structures.

“I noticed abandoned street posts with no signs on them,” he explains, “so I made boxes with passages from this document written on them that attached to the poles and were visible day and night. I wanted to juxtapose the city’s hopes for the neighbourhood with the infrastructure it left behind, to draw attention to this neglected area.”

This pointing to site occurs again in Buszchak’s Beacon, commissioned for Nuit Blanche Edmonton in 2015, in which the lighting system of an office building slowly flashes out its location in binary code: “This is the language that the building itself understands,” he explains. “I gave the code to the building in the same way you might give a score to a musician. I like to think that the audience for the piece might be the other buildings around it—they speak the same language.”

This post is adapted from the feature article “Break it Down,” generously supported by RBC in theSpring 2017 issue of Canadian Art. To get every issue of our magazine delivered to your door before it hits newsstands, visit canadianart.ca/subscribe.